Joseph Hunt

Mars Odyssey and NEOWISE Project Manager - NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL)

Contents

- Education

- What first sparked your interest in space, science, and engineering?

- How did you end up working in the space program?

- Tell us about your work.

- What's advice you would give to others interested in a similar career?

- What challenges did you face early on in your career as a Black engineer?

- Tell us about facing racism throughout your life.

- How do you deal with these challenges in your life and career?

- You survived Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in 2004. What was it like returning to work after your time off for treatment?

- Who inspired you?

- What are some fun facts about yourself?

- You saw the Columbia Space Shuttle being built and then launched on April 12, 1981. What was that like?

- Where are they from?

Education

Virginia State University

Engineering

Joseph Hunt was 13 years old when he watched NASA’s Apollo 11 astronauts land on the Moon on July 20, 1969. He was mesmerized by humanity’s first steps on the lunar surface.

But he never imagined he would grow up and work in space exploration. Instead, Joseph studied electronic technology and engineering at Virginia State University. He spent his post-college years working in military defense projects that took him from Northern Virginia to Massachusetts, South Carolina to Florida, and across the country to California. He worked on navigation systems for missiles and submarines, flight simulators for training Navy pilots, and even taught himself how to fly naval planes.

By the ‘90s, Joseph had made his way to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), lured by the opportunity to apply his skills to the quest for a greater understanding of the solar system and the universe. During his time at JPL, Joseph has worked on a variety of missions, including TOPEX/Poseidon and Cassini, and has earned three NASA medals along the way.

Joseph shares how he rose through the ranks as a young Black engineer in the ‘90s to become a project manager for key NASA missions.

What first sparked your interest in space, science, and engineering?

I was inspired as a child by watching TV and listening to the radio. I was always interested in how those products actually functioned. ‘How do those people appear on the TV? How did the sound come out of that box?’ When I became a young teenager, I built a radio. I was so excited when I went to turn the thing on, and it actually worked. RadioShack used to sell these project kits and I used to be crazy about them. As a result, I started fooling around with TVs and became the neighborhood TV repair kid.

How did you end up working in the space program?

The first time I heard about the JPL was in the ‘90s when I was working at Northrop Electronics in Hawthorne, California. JPL was having a job fair, so I went over [to the Lab] to check it out and they were talking about Mars Orbiter, TOPEX/Poseidon, and how they were ramping up those missions. For me, working in the defense industry for so many years, I was ready for a career change. Once I was introduced to JPL and all of the engineering and scientific things they were doing, I got really excited about space exploration. I wanted to stop building weapons. It was a chance to change from a defense perspective to going out and doing something that provided more science and technological contributions to the general community.

When someone is sharing their story that happened on another mission, you listen. And as a result of listening to them, when you are faced with that same scenario-slash-challenge, you take a different approach.- Joseph Hunt

Tell us about your work.

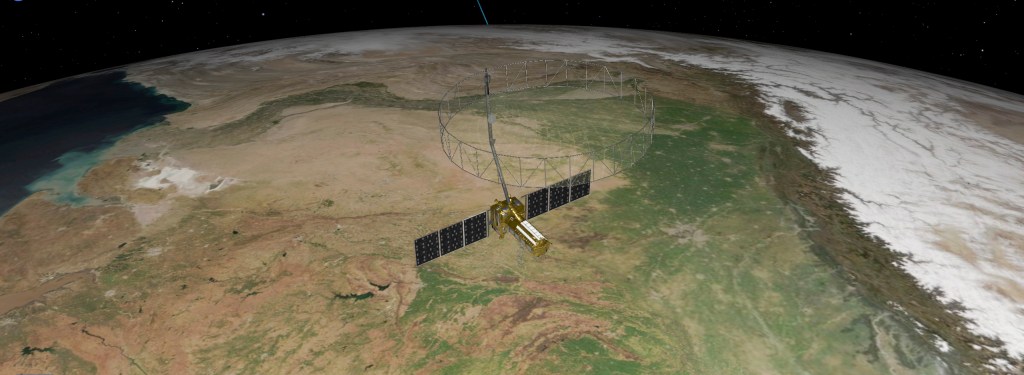

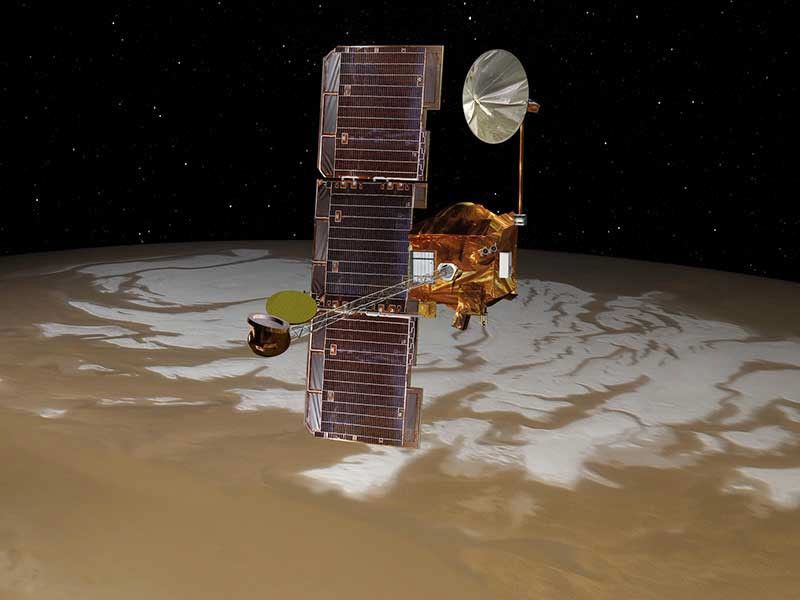

I’m project manager for NASA’s Mars Odyssey orbiter. I have responsibility for leadership and management of the spacecraft – providing oversight and direction for all extended mission activities.

Odyssey is NASA’s longest-lasting spacecraft at Mars. It was launched on April 7, 2001, and it arrived at Mars on Oct. 24, 2001.

I’m responsible for project coordination, planning, implementation guidelines, budget and schedules, and preparation of plans. I direct and control activities required to meet the project’s objectives in accordance with JPL and NASA policies, practices, standards.

I also work on the NEOWISE project. When I joined the mission, it was already a well-established mission with seasoned personnel in key roles, meeting the science objectives. I think Comet NEOWISE was a welcoming gift. All I had to do was take over from the previous project manager – who had done a fantastic job – and then maintain the continuity of operations.

I had to go from a mission I knew lots about, to a new mission with a whole new science objective and mission operation design. I had to learn about the mission, the organization, people’s names, and to be able to join the project in a way of leading by trust.

This all had to be accomplished working remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic, too. I had to establish with the team that I understood the mission science objective, the spacecraft, and the ground system, to the point that they embraced me as the new leader. That way, there’s no controversy because there was an early acknowledgment in understanding their roles and their jobs. It wasn’t like a leader coming in and changing everything the way they want it. It didn’t require change, just sustainment.

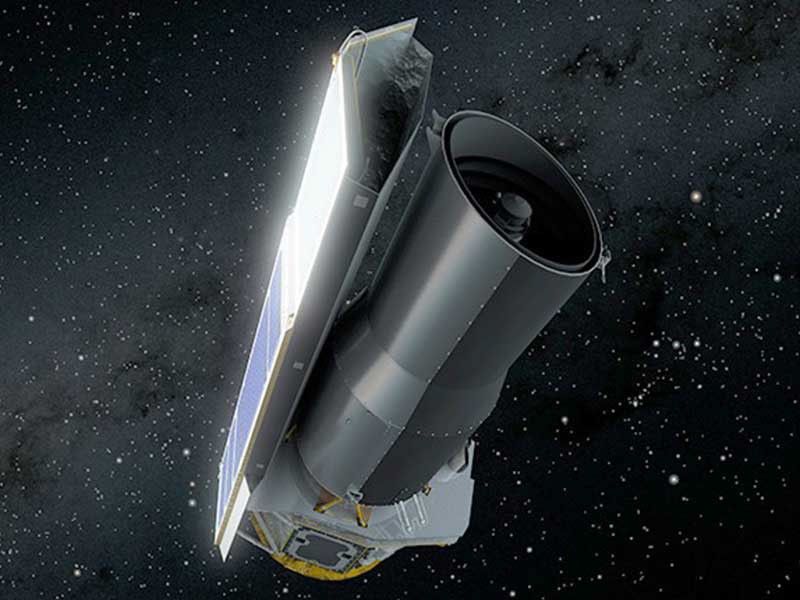

I also spent 19 years working on the Spitzer mission. It will always rank as one of NASA’s greatest observatories for studying the cosmos, and I can’t say enough about the people that contributed to such a successful mission.

What's advice you would give to others interested in a similar career?

I would say JPL offers a very diverse portfolio of job disciplines, which provides you with a lot of growth opportunities. It’s a fixed workforce, so there’s a strong likelihood of your coming back into association with people you’ve worked with in the past in different roles and responsibilities. So, if you’re faced with a challenge, and you feel that it’s personal, try to approach the person and talk to them. You have to be careful because that person might be your next supervisor, making your next recommendation, and sometimes we don’t know what’s driving the other person. Keep your relationships strong, even if they’re tough, in life.

What challenges did you face early on in your career as a Black engineer?

One of the first things I noticed about JPL when I came here [in the ‘90s] was the ethnic makeup of the workforce. Sometimes, it felt like there was no social outlet. There was no one that I could consult for their perspective on the environment, and there was very little insight into the culture. It was very interesting, too, because there was no formal mentoring at the time, at least that I was aware of. [Inclusion] got slowly better over the years, though. I just happened to be in that generation of change.

I always had this attitude for myself that I built my own mentorship population. The younger folk today call that networking. I built my own networking by being approachable and maintaining a receptive personality; it’s about being open. Early on, the people in my leadership network were mostly white men because they were the dominant leadership of JPL. That changed as the years went by. As that changed, my network changed. But I always had a diverse set of peers that were honest and open for the most part.

Tell us about facing racism throughout your life.

I was sheltered from [racism] by my parents when I was a kid, but once I started high school and started exploring places and venturing out, that’s when I was introduced to different situations. I’ve had a policeman pull me over with a gun to my window. I’ve been pulled over and told to pay in cash on the spot for a ticket. I had a Porsche 911 in the ‘90s and got rid of that car because I was getting pulled over by the police all the time. Back then, the thought was, ‘He must have stolen this car.’ The truth is, I was probably being racially profiled. Since I got rid of that car, I haven’t gotten a ticket.

Sometimes people say things at work and elsewhere and they really don’t know how it’s impacting you. On my insides, I’m irritated. But I can’t express that, because it’s like, ‘I personally do like you. I’ve liked you for years, but now do I doubt that?’ I think it’s important, though, because when I am experiencing this, people reveal what they are thinking, and I see society still has some problems. It tells me how far away we still are. Sometimes you think everything has changed [for the better], and then you get those subtle reminders of the work to be done.

How do you deal with these challenges in your life and career?

When you’re growing in life, there are going to be obstacles in your way. I was told by someone on Cassini, ‘When things become difficult sometimes, they’re tests. Don’t take it as an insult. You’re being challenged because there’s something better for you.’ It was the first time someone had said something to me that made those complicated situations feel like they were part of me growing. These are experiences that make you wiser. I wonder today, did that apply to everyone or did this person understand my challenges and wanted to give me words of encouragement? I really appreciated this person.

You also have to stay focused and not react to each scenario. You have to believe in your journey and thank God almighty there’s a higher power of faith that looks over us. I stay focused and just continue the journey.

You survived Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in 2004. What was it like returning to work after your time off for treatment?

I just tell myself I’m a survivor. I’m very determined. I set goals and I’m very determined to achieve my goals. My coworkers at JPL were very supportive. When I came back, my desk was just like I left it. I just went right back to work.

Who inspired you?

I learned a lot about telecommunications from one of the lead telecom engineers. I also learned a lot about engineering best practices and lessons learned, just from talking to people with mission operation experience. When someone is sharing their story that happened on another mission, you listen. And as a result of listening to them, when you are faced with that same scenario-slash-challenge, you take a different approach. You take some of the assumptions out of the equations because someone else has experienced those same conditions before you.

What are some fun facts about yourself?

After college, I started designing mobile communications modules for the Army. From there, I went to work on flight simulators. I learned that when they monitored Navy pilots after the Vietnam War, one of the scariest things for the pilots to do was land a plane at night on an aircraft carrier. My engineering partner at the time [on that job] was a bodybuilder, and he couldn’t fit into the plane’s cockpit, but I could. So, I performed the pilot functions and did the engineering testing for the avionics of the flight simulator. I never learned formally how to fly – I just knew friends with planes and worked with flight simulators. I guess if you practice anything enough, you can eventually do it. The Navy pilots were impressed with my flying (laughs).

You saw the Columbia Space Shuttle being built and then launched on April 12, 1981. What was that like?

I was totally intrigued by Columbia. I was working at Cape Canaveral and would frequently visit Kennedy Space Center for lunch and watch them build the shuttle. I had a friend and coworker who had a Cessna and one day, we flew across restricted air space while Columbia was sitting on the pad. I definitely would not do that today – I would get shot down (laughs). I saw the launch in person and it was the most patriotic I’ve ever felt in my life. You’re an American citizen and this is America at its best as you’re watching this thing take off. It was breathtaking.

Where are they from?

Planetary science is a global profession.