Enceladus

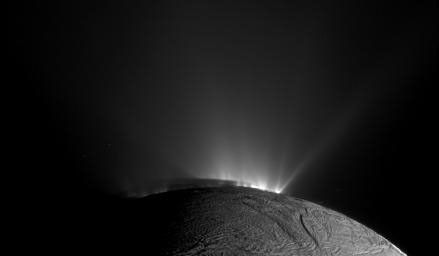

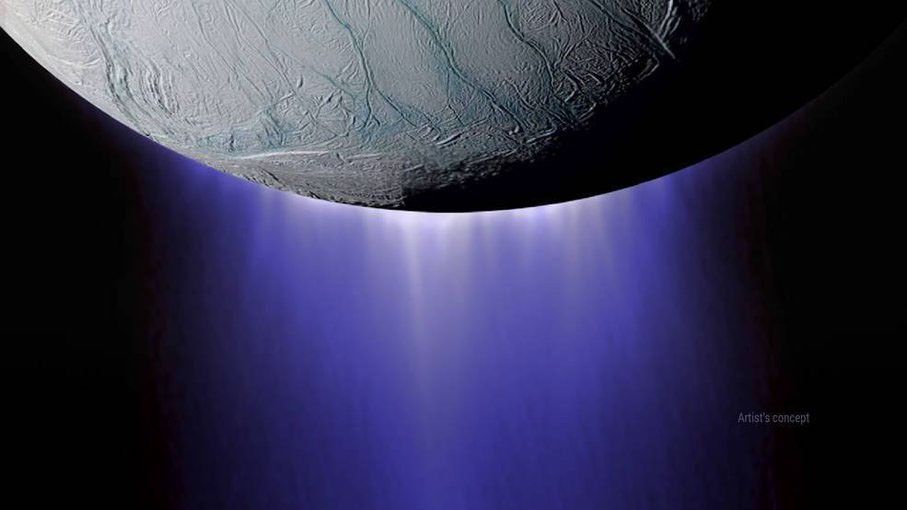

Geysers venting from Saturn's moon Enceladus give clues that its subsurface saltwater ocean could be a possible habitat for life.

Contents

Overview

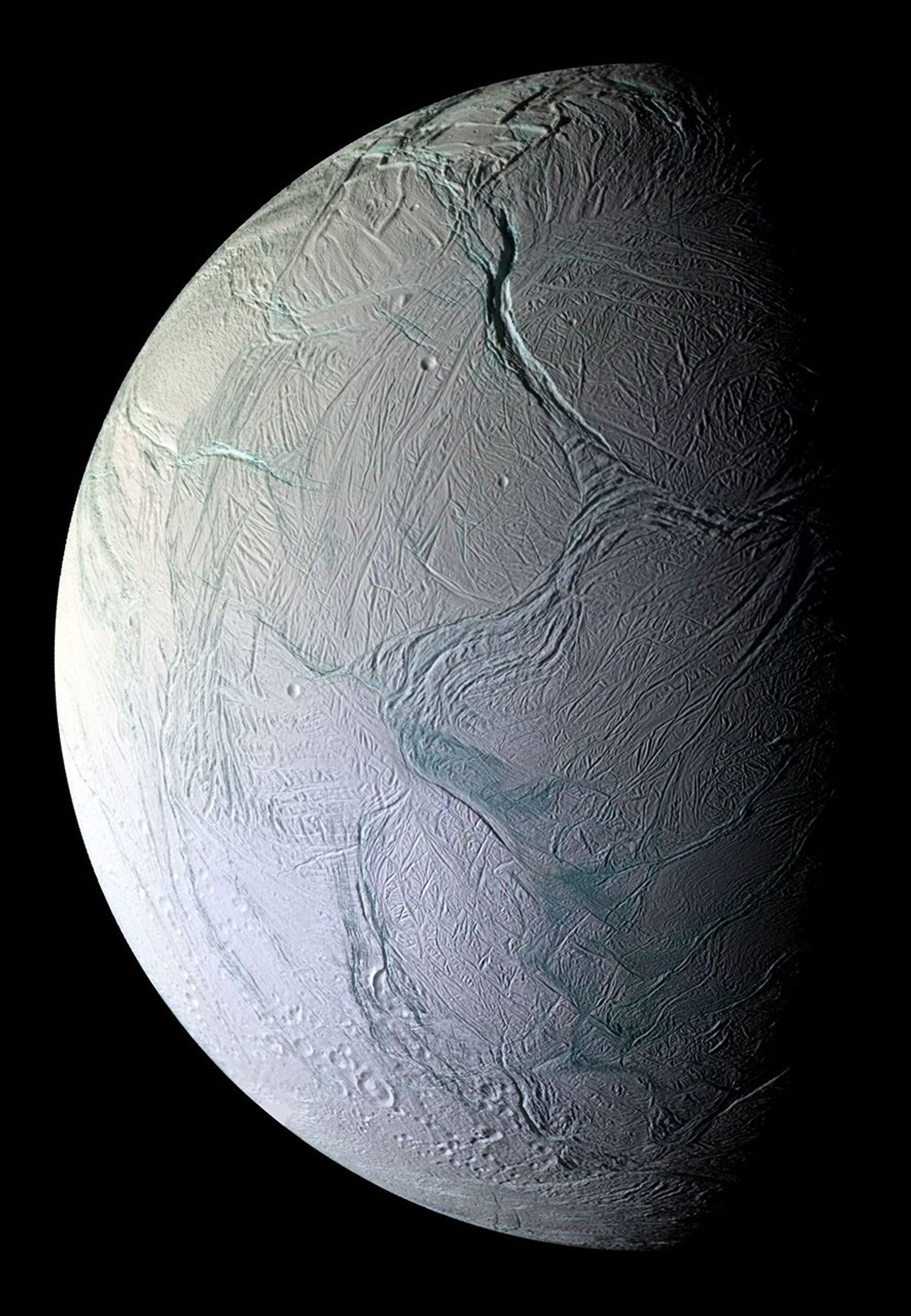

Saturn’s moon Enceladus is a small, icy world that has geyser-like jets spewing water vapor and ice particles into space.

Few worlds in our solar system are as compelling as Enceladus. A handful of worlds are thought to have liquid water oceans beneath their frozen shell, but Enceladus sprays its ocean out into space where spacecraft can sample it. From these samples, scientists have determined that Enceladus has most of the chemical ingredients needed for life, and likely has hydrothermal vents releasing hot, mineral-rich water into its ocean.

About as wide as Arizona, Enceladus also has the whitest, most reflective surface in the solar system. The moon creates a ring of its own as it orbits Saturn—its spray of icy particles spreads out into the space around its orbit, circling the planet to form Saturn’s E ring.

Enceladus is named after a giant in Greek mythology.

Pictures from the Voyager spacecraft in the 1980s indicated that although this moon is small—only about 310 miles (500 kilometers) across — its icy surface is remarkably smooth in some places, and bright white all over. In fact, Enceladus is the most reflective body in the solar system. For decades, scientists didn’t know why.

Because Enceladus reflects so much sunlight, the surface temperature is extremely cold, about minus 330 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 201 degrees Celsius). But it is not as cold and inactive a place as it appears.

Enceladus orbits Saturn at a distance of 148,000 miles (238,000 kilometers) between the orbits of two other moons, Mimas and Tethys. Enceladus is tidally locked with Saturn, keeping the same face toward the planet. It completes one orbit every 32.9 hours within the densest part of Saturn's E Ring. Also, like some other moons in the extensive systems of the giant planets, Enceladus is trapped in what’s called an orbital resonance, which is when two or more moons line up with their parent planet at regular intervals and interact gravitationally. Enceladus orbits Saturn twice every time Dione, a larger moon, orbits once. Dione’s gravity stretches Enceladus’ orbit into an elliptical shape, so Enceladus is sometimes closer and other times farther from Saturn, causing tidal heating within the moon.

Parts of Enceladus show craters up to 22 miles (35 kilometers) in diameter, while other regions have few craters, indicating major resurfacing events in the geologically recent past. In particular, the south polar region of Enceladus is almost entirely free of impact craters. The area is also littered with house-sized ice boulders and regions carved by tectonic patterns unique to this region of the moon.

In 2005, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft discovered that icy water particles and gas gush from the moon’s surface at approximately 800 miles per hour (400 meters per second). The eruptions appear to be continuous, generating an enormous halo of fine ice dust around Enceladus, which supplies material to Saturn's E-ring. Only a small fraction of the material ends up in the ring, however, with most of it falling like snow back to the moon’s surface, helping keep Enceladus bright white.

The water jets come from relatively warm fractures in the crust, which scientists informally call the “tiger stripes.” Several gases, including water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, perhaps a little ammonia and either carbon monoxide or nitrogen gas make up the gaseous envelope of the plume, along with salts and silica. And the density of organic materials in the plume was about 20 times denser than scientists expected.

From gravity measurements based on the Doppler effect and the magnitude of the moon’s very slight wobble as it orbits Saturn, scientists determined that the jets were being supplied by a global ocean inside the moon. Scientists think that the moon’s ice shell may be as thin as half a mile to 3 miles (1 to 5 kilometers) at the south pole. The average global thickness of the ice is thought to be about 12 to 16 miles (20 to 25 kilometers).

Since the ocean in Enceladus supplies the jets, and the jets produce Saturn’s E ring, to study material in the E ring is to study Enceladus’ ocean. The E ring is mostly made of ice droplets, but among them are peculiar nanograins of silica, which can only be generated where liquid water and rock interact at temperatures above about 200 degrees Fahrenheit (90 degrees Celsius). This, among other evidence, points to hydrothermal vents deep beneath Enceladus’ icy shell, not unlike the hydrothermal vents that dot Earth’s ocean floor.

With its global ocean, unique chemistry and internal heat, Enceladus has become a promising lead in our search for worlds where life could exist.

Discovery

British astronomer William Herschel spotted Enceladus orbiting Saturn on Aug. 28, 1789.

How Enceladus Got Its Name

Enceladus is named after the giant, Enceladus, of Greek mythology. William Herschel's son John Herschel suggested the name in his 1847 publication Results of Astronomical Observation made at the Cape of Good Hope, in which he suggested names for the first seven Saturnian moons discovered. He chose these names in particular because Saturn, known in Greek mythology as Cronus, was the leader of the Titans.

Ocean Worlds Resource Package

Explore this page for a curated collection of resources, including activities that can be done at home, as well as videos, animations, printable graphics, and online interactives.

Learn More