What is Webb Revealing About the TRAPPIST-1 System?

Contents

- Why is TRAPPIST-1 interesting? How are scientists using Webb to learn about the planets?

- What has Webb revealed about the TRAPPIST-1 system and its planets? And what do we still not know?

- Will Webb be able to search for signs of life in the TRAPPIST-1 system?

- How does the TRAPPIST-1 system tie into the broader story of exoplanets?

- Suggested resources

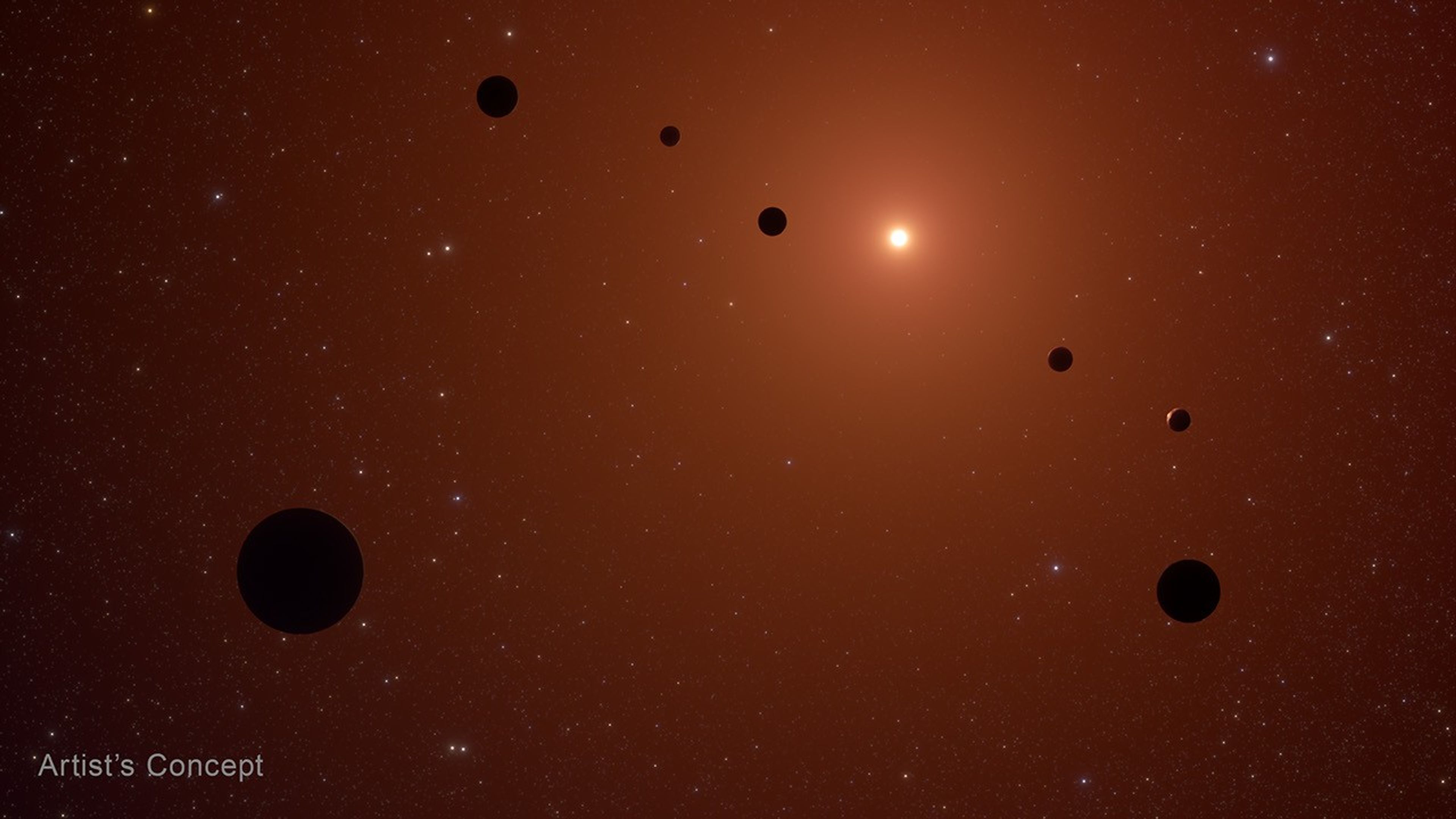

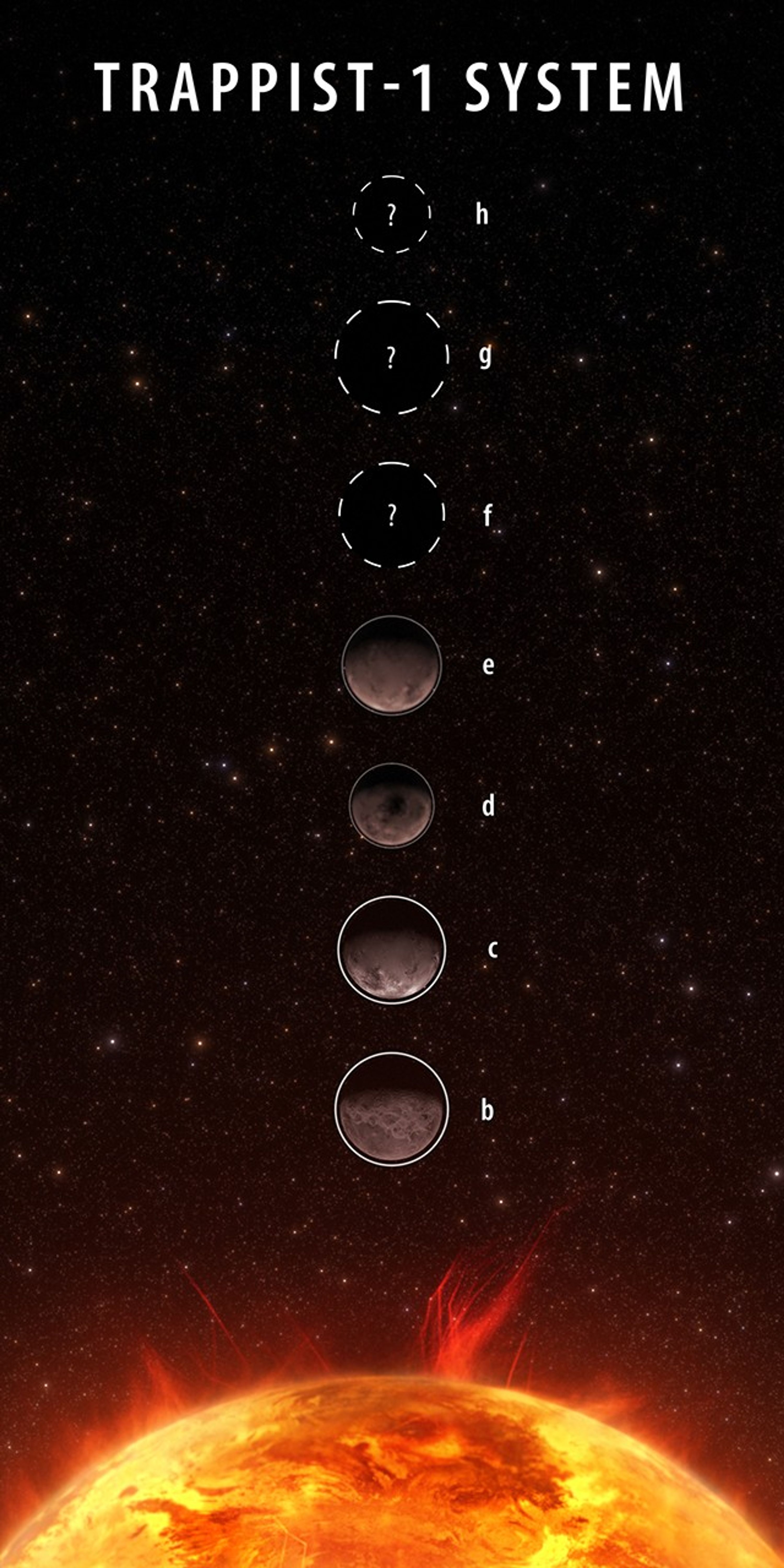

After scientists using the ground-based Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST) spotted what looked like three planets orbiting a red dwarf star in 2015, follow-up observations with space telescopes brought clarity: There are actually at least seven Earth-sized rocky worlds orbiting the star.

Named after the telescope, scientists have continued to observe the TRAPPIST-1 system with various space telescopes across different wavelengths of light, making it one of the most studied planetary systems aside from our own. With NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, a new chapter of the TRAPPIST-1 tale is underway — exciting and intriguing astronomers and the public alike.

Why is TRAPPIST-1 interesting? How are scientists using Webb to learn about the planets?

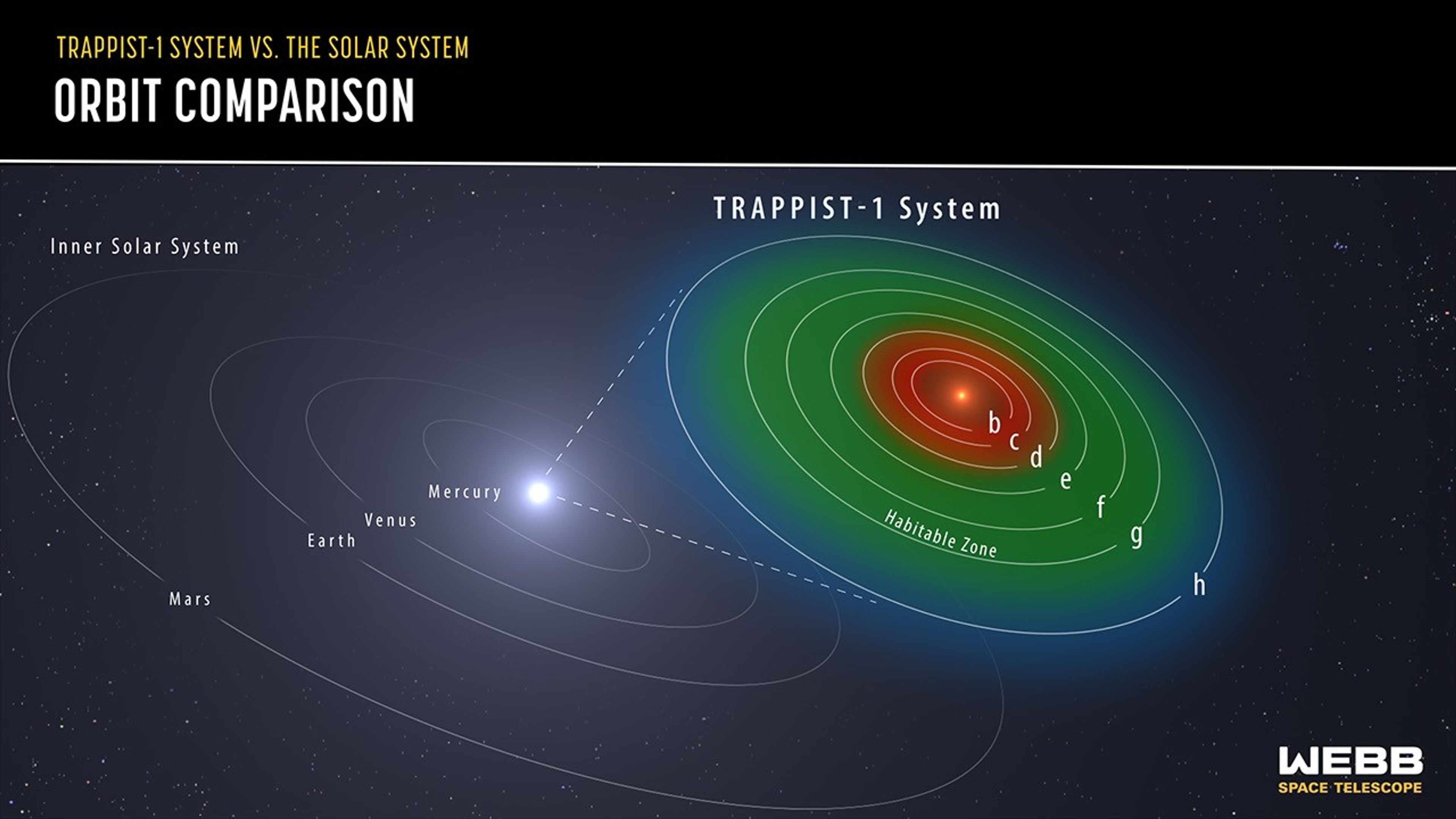

The TRAPPIST-1 system offers scientists the opportunity to study a relatively close planetary system that is both similar to and distinct from our own solar system. Based on NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope data, astronomers measured the planets’ sizes and masses, and calculated their densities. They discovered that all seven exoplanets (b to h) are Earth-sized and probably rocky like Earth.

However, the TRAPPIST-1 system does have qualities that differ from our own solar system, which make it favorable for study at a relatively close distance of 40-light years.

- Compactness. All seven planets orbit closer to their star than Mercury (the innermost planet in our solar system) does to the Sun.

- Orbital period. The planets’ orbital periods range from 1.5 to roughly 19 days. Data from the planets’ multiple transits across the face of their star can be collected over a short period of time.

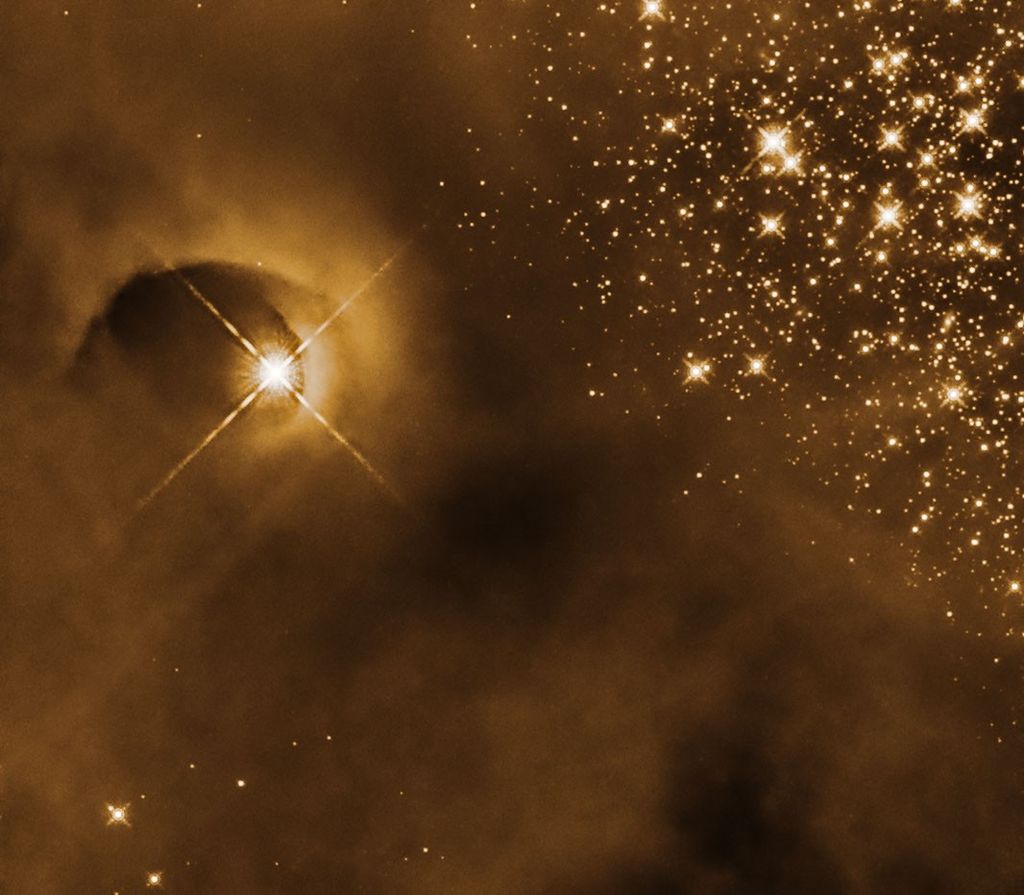

- Host star size. The ultra-cool red dwarf star is approximately 12 percent the radius of the Sun (so just slightly larger than Jupiter), making it easier to study the planets as they transit since they cover a larger fraction of the star’s surface than they would if the star was larger.

Spitzer data also indicated that three of the TRAPPIST-1 planets (e, f, and g) are in the habitable zone. This area around the host star is where the conditions are just right for liquid water to exist on a planet’s surface.

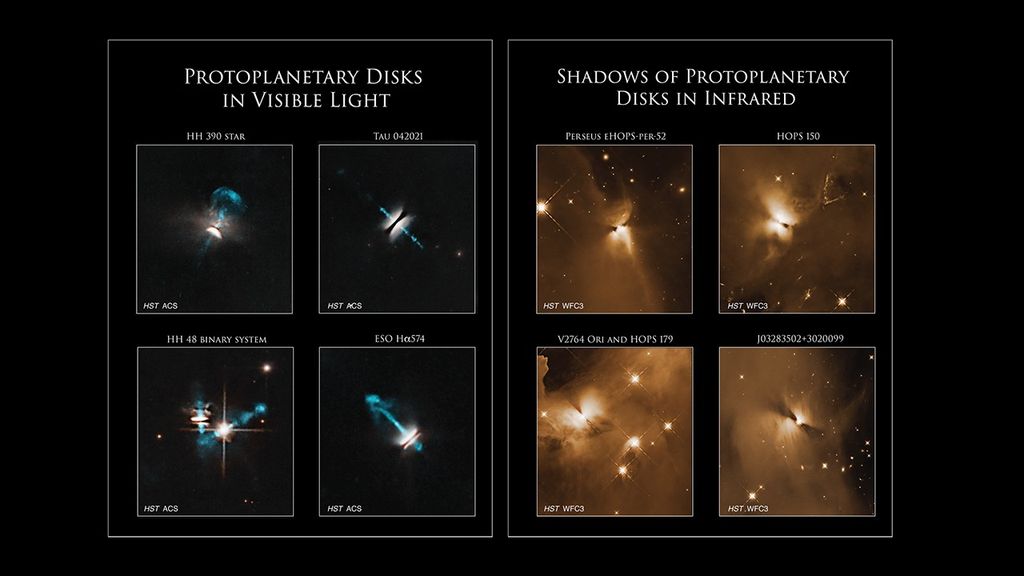

Whether these planets could have liquid water depends in part if they can hold an atmosphere. Astronomers used NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope to inspect their atmospheres, which ruled out the presence of puffy hydrogen-rich atmospheres similar to that of Neptune for some of the planets.

When Webb launched in 2021, it moved past the wavelength and stability limits of earlier observatories, opening up atmospheric study in a way they couldn’t. Webb’s position around L2, infrared sensitivity, and larger mirror make it the only telescope able to continuously lock onto an observational target, collect the optimal wavelengths of light, and observe the faint signals at a precision needed for exoplanet atmosphere characterization.

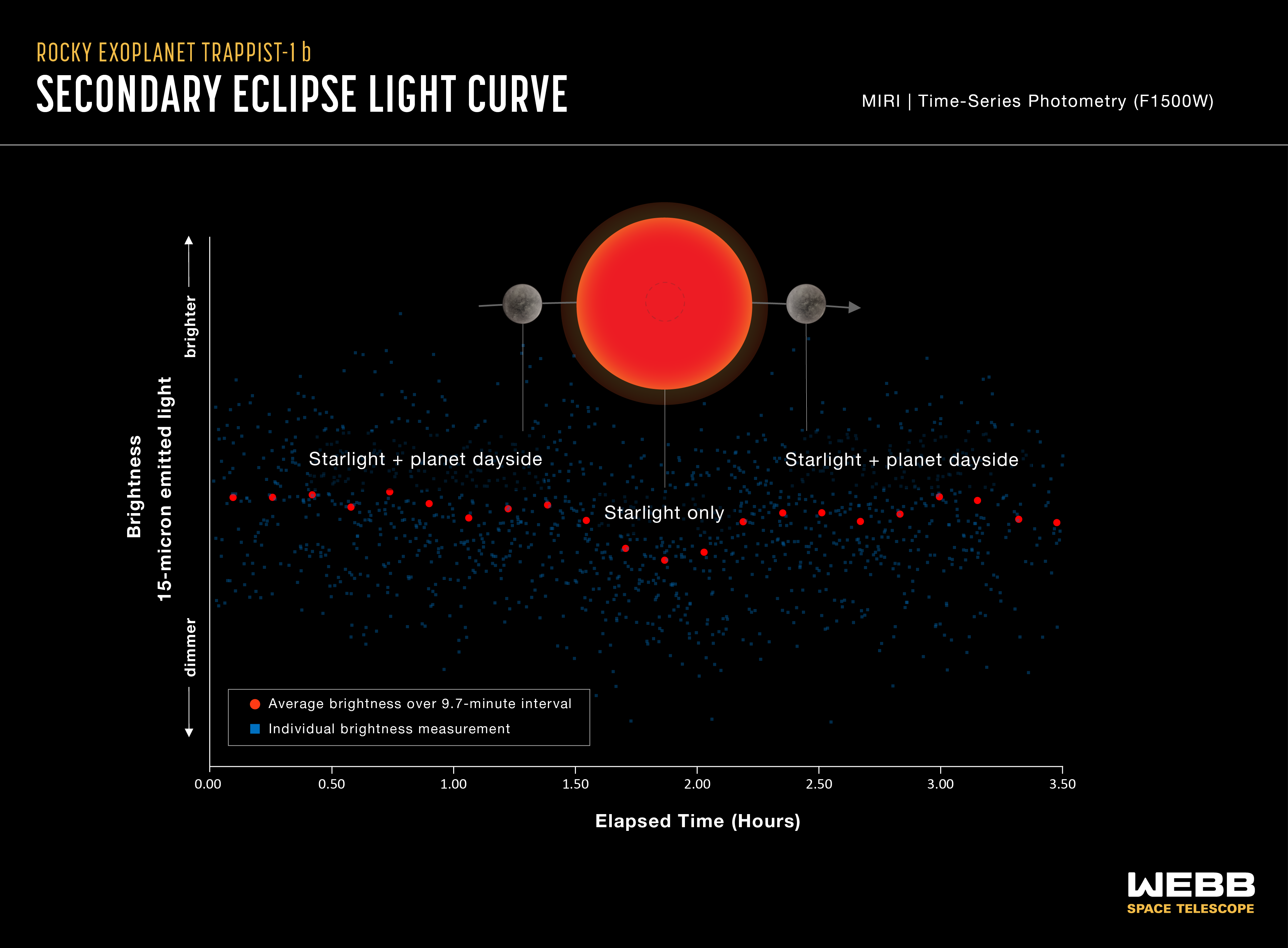

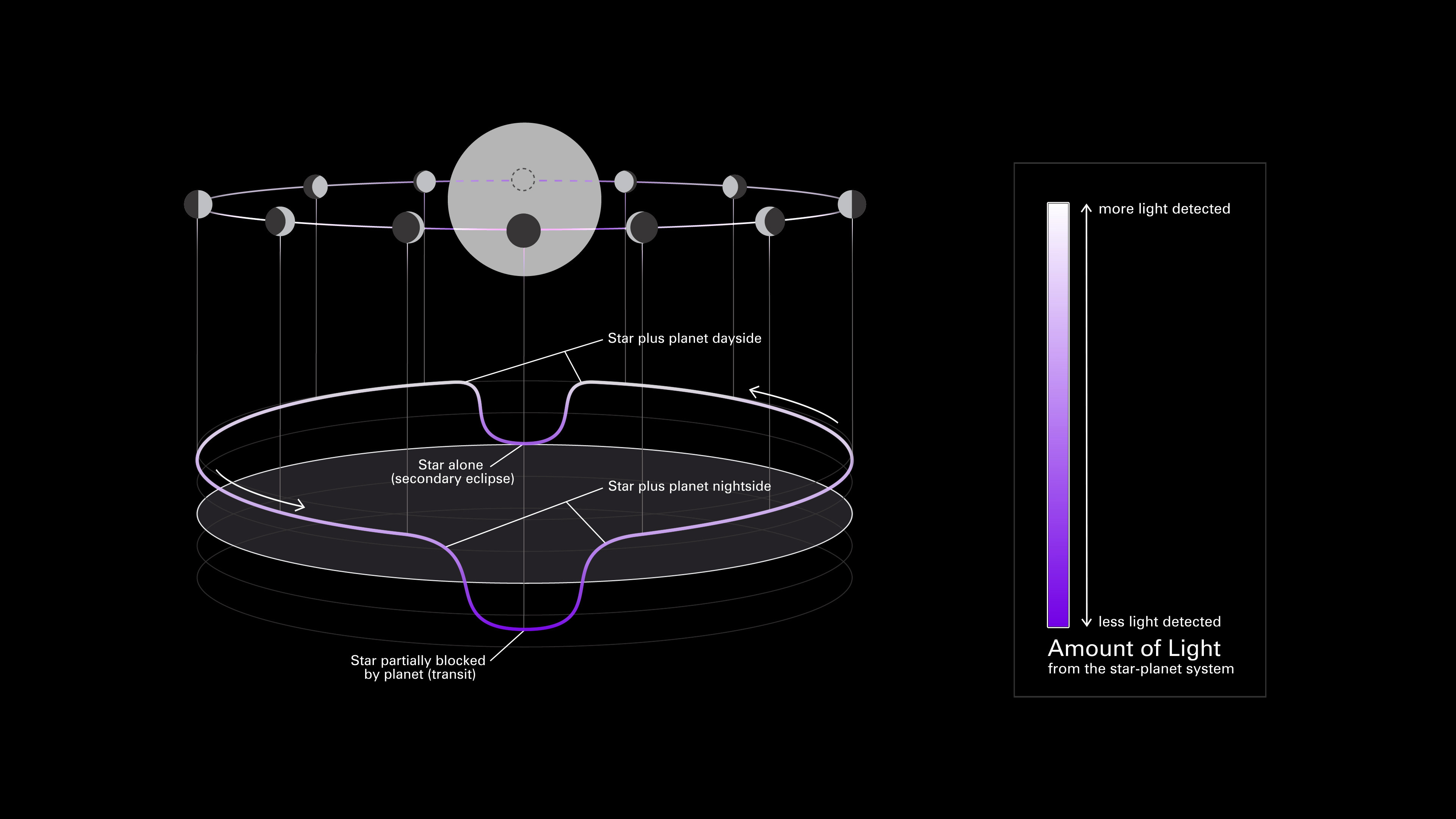

Since direct imaging of these planets is not possible because of how close they are to their host star, scientists use different approaches to learn about the system. Each method provides one piece of the puzzle that is necessary to determine whether the TRAPPIST-1 planets have atmospheres. Collectively, the data from Webb is providing scientists the ability to investigate the system’s formation and consider how common these environments are.

- Transit. When a planet moves between its star and the telescope, blocking some of the starlight.

- Secondary eclipse. When the planet moves behind the star and the light coming from the planet is blocked.

- Phase curve. The star-planet system’s changes in brightness as the planet orbits its star.

What has Webb revealed about the TRAPPIST-1 system and its planets? And what do we still not know?

Data has been successfully collected for all seven planets. As of December 2025, the science community has reported on their Webb observations for four of the seven TRAPPIST-1 planets: b, c, d, and e. So far, Webb hasn’t seen signs of thick atmospheres on TRAPPIST-1 b and TRAPPIST-1 c. The current data for b suggests it may be a bare rock with no atmosphere. If c does have an atmosphere, it’s very thin. For TRAPPIST-1 d and TRAPPIST-1 e, the data is still under study. For now, scientists have ruled out that these two planets have thick hydrogen atmospheres.

While scientists expected the red dwarf host star to be active, its activity is much more intense than originally predicted. TRAPPIST-1’s stellar flares and star spots make it challenging to distinguish between signals from the planets’ atmospheres and “contamination” from the star’s activity. To mitigate such challenging conditions, astronomers will have to take more observations than anticipated.

Advances in our scientific understanding are often gradual, and the study of the TRAPPIST-1 system is no exception. To become more certain in the atmospheric characterization of these planets will require follow-up observations of potentially hundreds of transits with Webb over several years.

Will Webb be able to search for signs of life in the TRAPPIST-1 system?

Webb will help scientists determine which planets do or don’t have atmospheres, therefore helping scientists understand some of the dynamics of atmosphere loss and retention.

If any of the planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system have atmospheres, Webb can begin to study their chemical compositions, which could offer tentative clues about habitability. However, Webb is not likely to detect biosignatures on these planets.

How does the TRAPPIST-1 system tie into the broader story of exoplanets?

TRAPPIST-1 is an exciting case study, serving as a rich data point that ties into our larger interest in exoplanets. The currently underway Rocky Worlds Director’s Discretionary Time program is a Webb-Hubble collaboration to answer whether planets around red dwarf stars (like TRAPPIST-1’s star) are able to retain atmospheres.

Astronomers will learn even more about the population of Earth-sized exoplanets with the future Habitable Worlds Observatory, and will continue studying TRAPPIST-1 and other planetary systems with the European Southern Observatory’s upcoming Extremely Large Telescope.

The scientific tale of TRAPPIST-1 is still being written. Each observation by Webb brings forth new information, gradually building our knowledge and shaping how we perceive these distant worlds, and driving our shared sense of excitement for what’s yet to come. We can’t help but wonder: What will we discover next about this system?

By Abigail Major

Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, MD

Suggested resources

- Science Explainer: Webb’s Impact on Exoplanet Research

- Science Explainer: Can Rocky Worlds Orbiting Red Dwarf Stars Maintain Atmospheres?