4 min read

Extreme weather predictions on the West Coast could become more accurate with help from NASA's remotely piloted Global Hawk. Flights to look at Pacific storms as they develop began Feb. 12.

The mission will show how Global Hawk could augment satellites and routinely fly vast areas of the ocean, said Robbie Hood, director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Unmanned Aircraft Systems program.

"How do you use Global Hawks and actually chase storms?" Hood asked. "That's what we are looking at with these missions."

NOAA, NASA and the National Weather Service are partnering on an El Niño field research campaign "to get data in the hands of forecasters and for our weather models," said Robert Webb, Physical Science Division director of the Office of Ocean and Atmospheric Research for NOAA.

Webb and a panel of experts from NASA, NOAA and the National Weather Service detailed elements of the campaign at NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center in California Feb. 5.

The observation flights are part of an ongoing NOAA mission called Sensing Hazards with Operational Unmanned Technology, or SHOUT. SHOUT is a multi-year mission to show how the use of autonomous vehicles can fill in gaps in weather modeling and as a potential backup in case a satellite is unable to capture data.

This SHOUT mission is being conducted in collaboration with NOAA's larger El Niño Rapid Response Field campaign. In addition to the Global Hawk, NOAA also is using a Gulfstream IV research plane and the NOAA ship Ronald H. Brown.

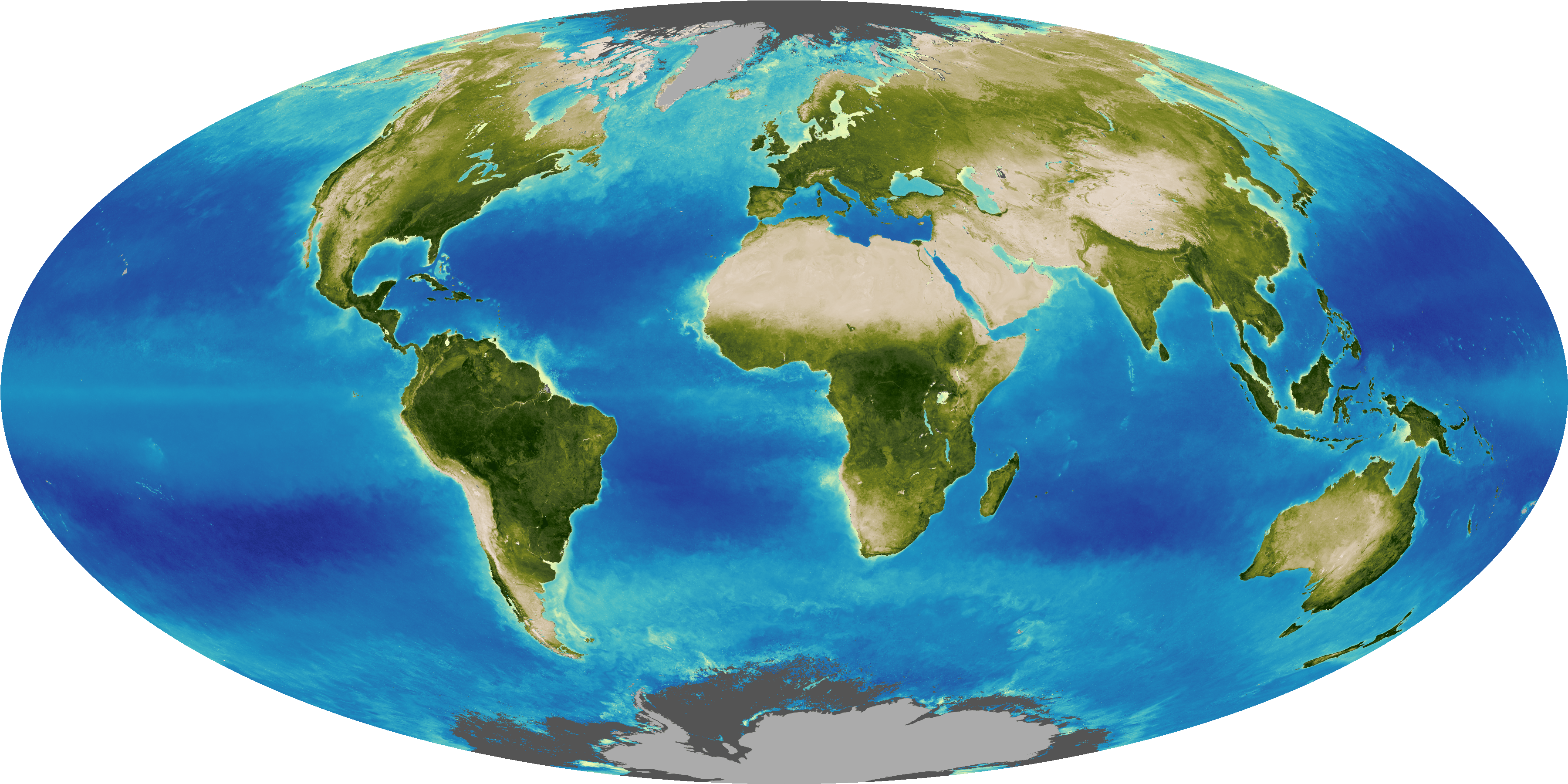

El Niño is a recurring climate phenomenon, characterized by unusually warm ocean temperatures in the equatorial Pacific, which increases the odds for warm and dry winters across the Northern United States and cool, wet winters across the South.

Based at NASA Armstrong, the Global Hawk is scheduled to fly four to six, 24-hour flights in February at 60,000 feet altitude. The aircraft is expected to provide detailed meteorological measurements from a region in the Pacific that is known to be the origin point of El Niño storms and particularly critical for interactions linked to West Coast storms and rainfall.

The Global Hawk can help fill a void over the Pacific Ocean that other assets, like satellites, cannot easily study, especially in the upper atmosphere where clouds can obscure observations, Webb said.

"It gives us a chance to really get ahead of the storm," he added.

Some of that data is collected through the use of tools resembling paper towel tubes called dropsondes. These devices are dropped from the Global Hawk into the weather to gather temperature, moisture and wind speed and direction, Webb said.

Also onboard the Global Hawk is the High Altitude Imaging Wind and Rain Airborne Profiler (HIWRAP) instrument, operated and managed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and the High Altitude MMIC Sounding Radiometer (HAMSR) instrument, managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The instruments will collect remote observations of the area, producing data similar to satellite observations.

The final instrument, NOAA-O3, will measure ozone at the altitude the aircraft is flying. Doppler radar is also used to track wind speed and direction.

"Every place the Global Hawk flies is like a layer cake and we see how it stacks up," Hood said. "The data can be cross referenced and map areas in and around the storm, and we can watch how it develops. We are interested in understanding the data that can improve our ability to predict extreme weather."

Gary Wick, lead NOAA scientist for the SHOUT mission, said the long-endurance flights provide information over a large area of the ocean like satellites do, but with greater resolution because the instruments are that much closer to the weather.

"The SHOUT campaign will provide unprecedented information that will improve hurricane predictions and add to weather models in areas of prediction that the models just don't get right," said Jason Sippel, a National Weather Service scientist.

Frank Cutler, the Armstrong Global Hawk project manager, said NASA Armstrong's role extends beyond providing the aircraft. Armstrong staff members are responsible for integrating the instruments into the aircraft, planning the missions as directed by the science team and then flying those missions.

Although the aircraft is autonomous, the Global Hawk can be sent instructions in flight to alter course to better observe items of interest based on changing conditions and "complete the mission with a perfect landing every time," Cutler explained.

As the current El Nino situation evolves, the Global Hawk will help determine what the storms look like and provide information for models to help better predict how the big storms develop.