Delta-X Field Stories: Collecting “Marsh Popsicles”

By Amanda Fontenot, Louisiana State University /NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA/

Although most of my work happens in the lab, office, or home, field days are some of the most important days of the year for my research. “Going to the field” is when we get to physically visit the wetlands that we spend so much of our time describing, researching, and caring about. Field days can require a lot of effort and time to execute, but they can also be a beautiful time to get out of the office and even have some fun with our colleagues.

I am a graduate student at Louisiana State University (LSU), and I am working towards my Masters of Science in Coastal and Ecological Engineering. I work with Dr. Robert Twilley in the Coastal Systems Ecology Lab at LSU, and my thesis research falls under NASA’s Delta-X Project. In October 2019, Dr. Andre Rovai and I laid a total of sixty-nine feldspar marker horizons at our seven Delta-X field sites in order to measure short-term sediment accretion. This March we traveled back to our markers in the Atchafalaya and Terrebonne basins of coastal Louisiana to measure this accretion.

We made these “markers” by pouring custer feldspar (a fine, white, mineral powder used in ceramics) on top of the soil surface. We use this material because it stays intact and provides a clear indication of when the experiment started. Over time, a soil layer forms on top of the white marker from both plant production and material that is deposited from rivers and the Gulf of Mexico. After placing the marker, our team comes back every 6 months and measures how thick that newly formed soil layer is on top of our marker. We then can divide that number by how many days it has been since we laid the marker, and we end up with a short-term sediment accretion rate. This rate is important in understanding how these wetlands will compete with increasing sea levels and local subsidence that threatens a majority of Louisiana’s coastal wetlands.

Most field days start pretty early in the morning, and this campaign was no exception. Our LSU team (Dr. Andre Rovai, Brandon Wolff, and I) left campus around 4:30 a.m. and headed to the boat launch to put our boat in the water. Since these sites are pretty mucky and we need to be careful to not step on our markers, we also travel with an airboat and our handy dandy airboat operator, Cade. After the boats are in the water, we drive to our sites and get to enjoy a nice sunrise on the water.

Depending on the morning, we usually get to our site around 9:00 or 10:00am and huddle up for a game plan. For this campaign, we needed to complete four tasks at each site: 1) measure accretion on top of our feldspar markers, 2) collect 50cm deep soil cores that help characterize the site, 3) deploy two water level recorders that collect data every 15mins, and 4) measure marsh elevation at varying points using our RTK instrument, which uses satellite-based positioning systems like GPS to estimate the elevation of a point. In the morning, we usually discuss in what order we might finish these tasks and who is in charge of each part of the process.

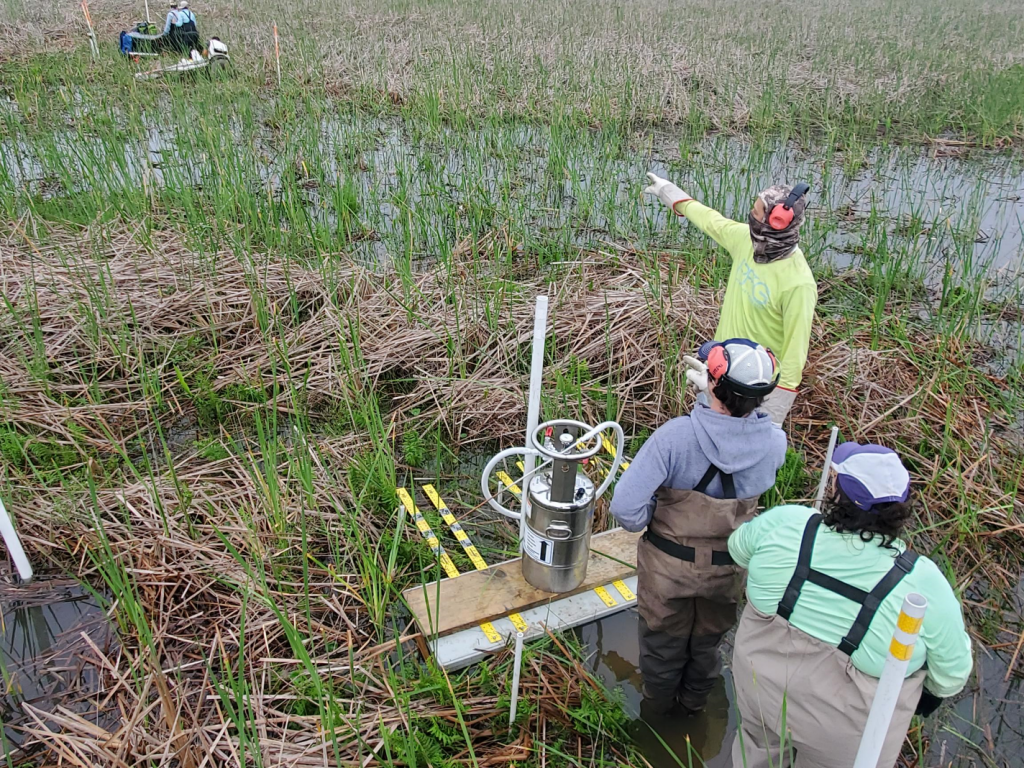

Most days, I am the one measuring and recording our accretion numbers for the feldspar markers. In order to minimize how much we disturb the soil around and within our feldspar marker, we use what’s called a “cryo-coring” technique – which we have affectionally named collecting “marsh popsicles.” In the field, we push a long, skinny copper pipe into the soil where we previously laid our marker and pump liquid nitrogen into the pipe. Since the liquid nitrogen gets so cold, some of the soil freezes around the pipe and ‘Voilà!’ we pull up our “marsh popsicle.”

On our popsicles, we see our feldspar marker as a white ring around the muddy popsicle. I measure the distance from the top of our popsicle (marsh surface) to that white ring (feldspar marker) with calipers and record it in my field notebook to look at later. Usually by the time we collect all the popsicles we need at the site, we go collect our soil cores and then are ready to eat lunch. We bring our own lunch to enjoy but what’s almost guaranteed is a plethora of light blue Gatorade and Andre’s signature glass bottle of Coke.

After lunch, we continue working on the other tasks for a few hours and try to help out the other field team from Florida International University (FIU) if we finish up before them. When we all finish up our field tasks, we start the long journey home. We pack up our supplies, put samples on ice, change clothes if we got too messy or wet in the field – those boat rides can get really chilly otherwise — and drive the boats back to the launch. At the launch, we get the boats back on the trailer and drive back to LSU, arriving later in the evening.

Depending on the weather, we might go out to another site the next day, meaning a meeting time of 4:30 a.m. back at the school. After we finish at campus, I race home to shower, eat dinner if we haven’t stopped somewhere on the drive back to Baton Rouge, clean my field clothes, and jump in bed to do it all over again the next day. Each team member plays an important role in the field, whether that be holding open bags to store samples, operating our liquid nitrogen tanks, or making sure everyone stays hydrated while we work. Although field days can be quite tiring and stressful, the work that our team accomplishes not only works towards the goals of the Delta-X project but increases the general knowledge of Louisiana’s coastal wetlands and the ecosystem services they provide.