Are you ever fooled by relief inversion?

Satellite sensors provide an unprecedented perspective on our planet. Some zoom in for spectacular detail, while others take the wide view. But while our eyes in the sky give us encyclopedias full of information, they can give us something else: optical illusions.

Many of us have an unconscious expectation to see objects illuminated from above. When looking at paintings or photographs, this means we often expect the light source to occur somewhere off the top edge of the picture. In satellite images, however, this is not always the case.

Earth Observatory generally follows the convention of orienting satellite images so that north is up. For images of the Southern Hemisphere, this rarely presents a problem. But for images of the Northern Hemisphere, sunlight usually comes from the south. Where sunlight illuminates south-facing slopes and leaves northern slopes in shadow, many viewers experience an optical illusion known as relief inversion.

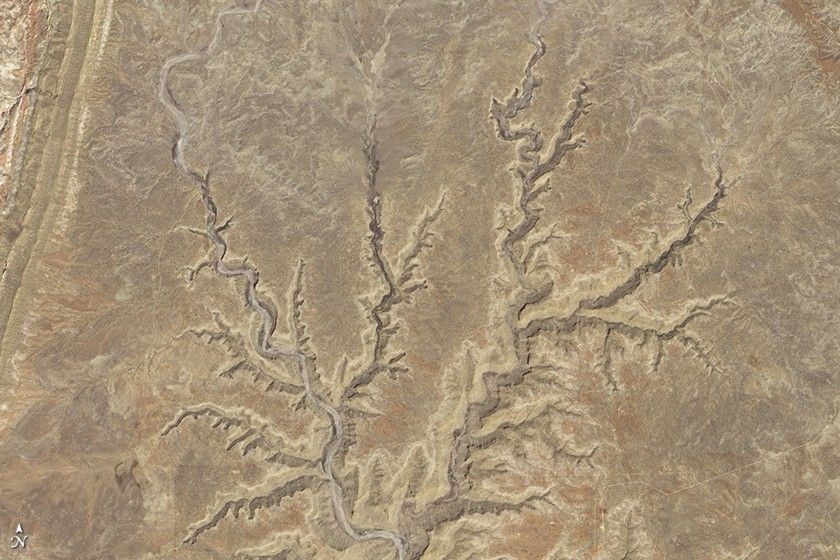

One example of relief inversion comes from the southwestern United States, in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. When north is up, an elaborate network of canyons in the national monument appear, to some viewers at least, to rise above the surrounding land.

When the image is rotated, the canyons look like canyons.

Relief inversion is also pronounced in images of mountainous areas, such as the Bhutan Himalaya.

As before, rotating the image 180 degrees alleviates the optical illusion and makes it easier to identify glaciers flowing downhill and terminating in the glacial lakes.

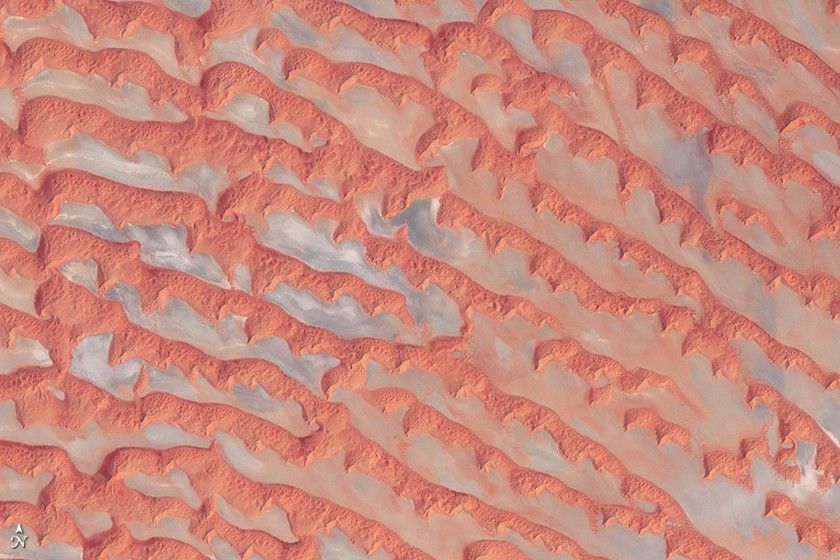

Perhaps the biggest hazard of relief inversion is that it’s possible to be misled without even realizing it. This is especially true when looking at images of unfamiliar landscapes that few of us encounter in person. The Arabian Peninsula’s Empty Quarter, known as Rub’al Khali, is a huge expanse of shifting sand dunes. When north is up, the salt flats between the dunes appear elevated.

When the image is rotated, this alien landscape is easier to interpret.

A simple solution to relief inversion is to view satellite images from multiple angles — such as printing a copy and turning the page upside down, or using a photo editing software program to rotate the image. If a landscape looks puzzling, try looking from a different angle.

For more information, read “Perceptual biases in the interpretation of 3D shape from shading,” or “Getting real: Reflecting on the new look of National Park Service maps” (PDF).