From the Archives: NASA’s Goddard Instrument Field Team on the Island of Hawaii

Editor’s note: This blog entry is adapted from content originally published on NASA social media accounts in September 2022.

In September 2022, researchers from NASA’s Goddard Instrument Field Team (GIFT) were guests on the island of Hawaii, studying volcanoes and caves. The team investigates our planet’s most otherworldly places, working to answer questions about our solar system’s history and the search for life beyond Earth.

Special thanks to Hawaii Volcanoes National Park and the Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI-SEAS) for hosting us as visiting researchers. We’re all visitors here. Hawaii’s volcanoes and caves have been cherished cultural landscapes since long before NASA existed.

Hawaii’s volcanic terrain has much to teach us about our planet and our place in the universe. Volcanic activity is common throughout our solar system, and Earth rocks are very similar to rocks on other worlds.

Searching for life (or not-life)

At the very beginning of the expedition, before the rest of the team arrives and breathes all over the work site, the astrobiologists get to work. Human contamination could get in the way of their search for signs of tiny life forms.

Inside the lava cave, scientists Bethany Theiling and Jen Stern of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center set up a makeshift lab. Their questions: What kinds of microbial (invisibly small) life might these cavern walls hold? What gases do those life forms release? Can we find out by testing the air in the underground chamber?

They’re also on the lookout for false positives, or things that appear to be signs of life but actually aren’t. For example, some parts of the cave wall are coated with a veiny texture. These patches could be evidence of microscopic life or just cracks in the rock face.

Get the full story of this expedition’s astrobiology research in the next episode of NASA’s Our Alien Earth.

Lava caves: not just an Earth thing

The space where Theiling and Stern are working is an empty tunnel left behind by flowing lava after a volcanic eruption. Lava caves like this one are found on the Moon, on Mars, and in many places on Earth.

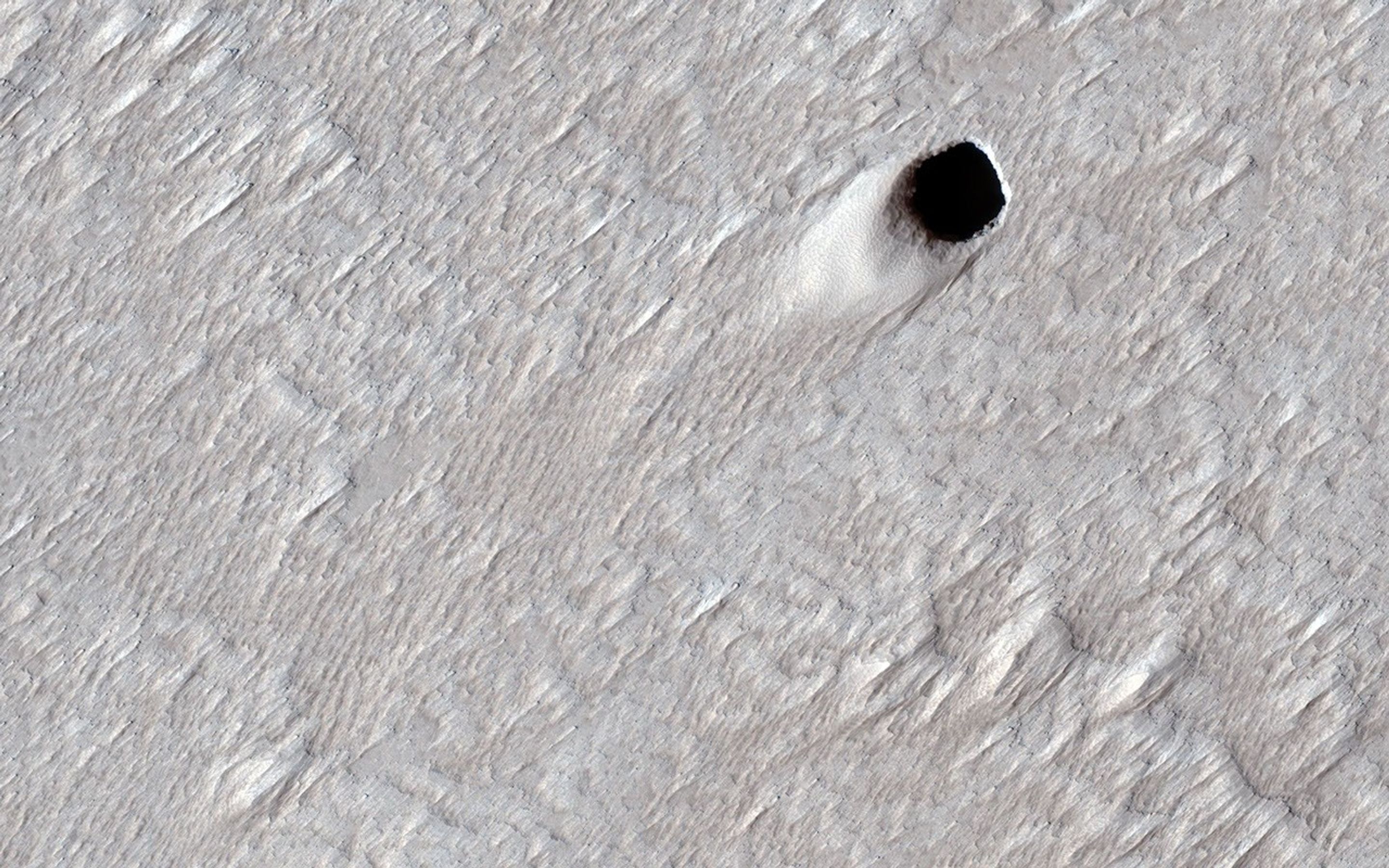

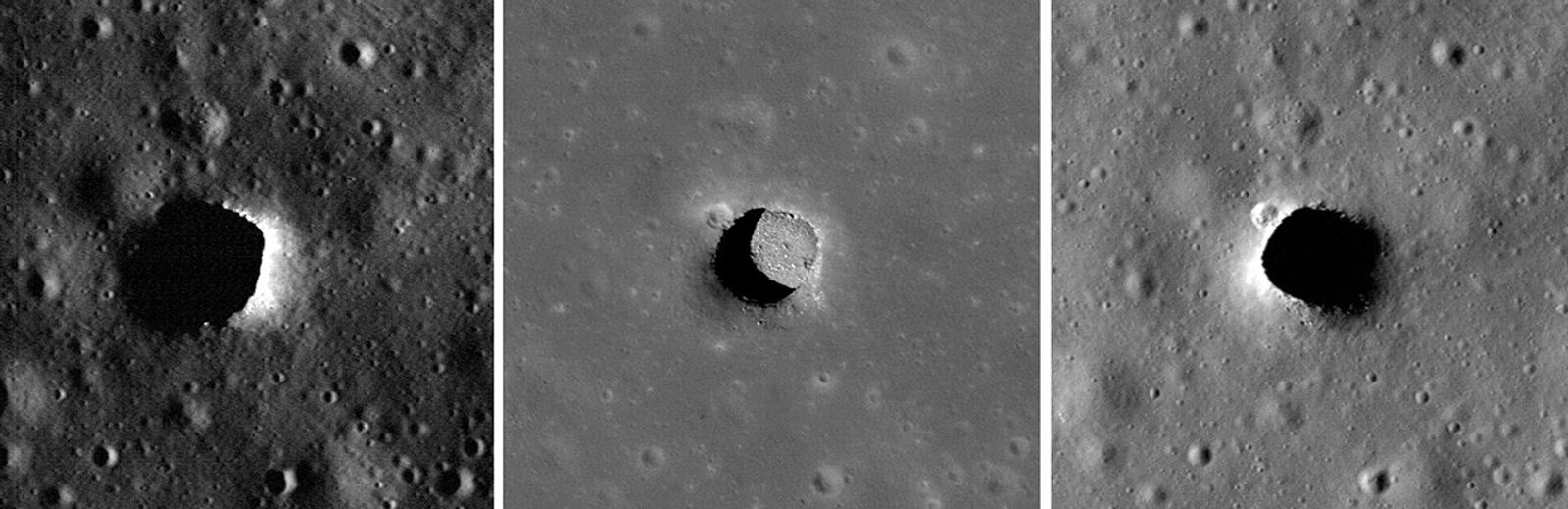

Here’s an example of a lava cave opening on Mars, photographed from orbit. The mouth of this cave is about 150 feet (50 meters) across, or roughly half the length of a soccer field—several times wider than the entry to the cave where we’re working on Earth.

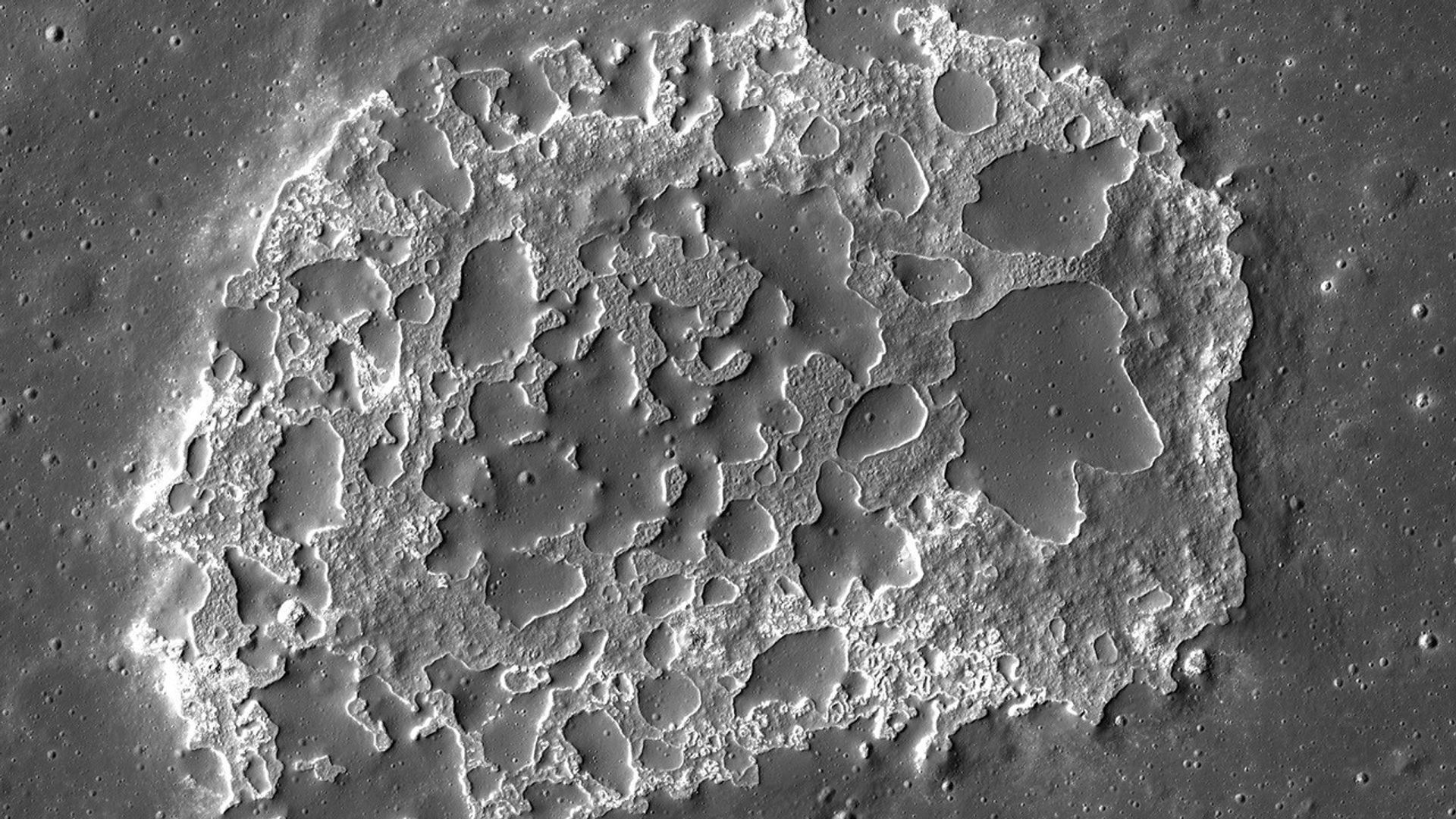

And here are three views of a single lava tube opening on the Moon, captured from orbit at different times of the lunar day. In July 2022, scientists discovered that the temperature inside of this cave always hovers around a comfortable 63 F (17 C).

Underground caves on the Moon create natural shelter from harsh space radiation, and are spaces where human and robotic explorers could someday seek refuge. That’s why we’re testing tools and techniques here on Earth that could help astronauts to detect and investigate caves on other worlds.

Headlamps below ground, magnetic field detector above

Above ground, several team members get ready to enter the lava tube. It takes about 20 minutes to gear up and get underground safely. Each person’s protective equipment includes a helmet, headlamp plus two backup light sources, high-visibility vest, knee pads, and work gloves.

We can’t see it from the first worksite, but another giant tunnel lies nearby beneath this lava landscape. The magnetometer team uses a portable magnetic field detector to look for telltale signs to detect it from above ground. As they walk over the cave roof, the detector’s readout changes, revealing the tunnel below.

We’ve been refining this magnetic field detector all year and working hard to make it better. It can already collect measurements 10 times faster than it did a few months ago. This is just one of the kinds of tools that future Moon explorers could use to detect caves hidden under the lunar surface.

From Moon IMPs to modeling MAHLI

In Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, Marie Henderson of NASA Goddard and Hunter Vannier of Purdue University analyze clumps of foam-like volcanic glass. These delicate, bubbly rocks may unlock a Moon mystery.

The device in Vannier’s hand is a spectrometer. It sends a beam of light towards a test object, like the ground or a foamy piece of volcanic rock, and measures the signal that bounces back. The readout tells us what the target material is made of.

Henderson and Vannier are working to solve a science mystery: irregular mare patches, or IMPs. These patches are weird places on the Moon that appear much younger than the land around them, and we’re not sure why. Finding out will tell us more about how lunar geology works. As usual, our search for answers starts here on Earth.

Close-up observations of Earth rocks help us understand what we see in orbital images of the Moon. Some scientists think the Moon’s IMPs might contain rocks made of fragile air bubbles, like the one shown above. We’ll compare field data with data collected in lunar orbit to test the theory.

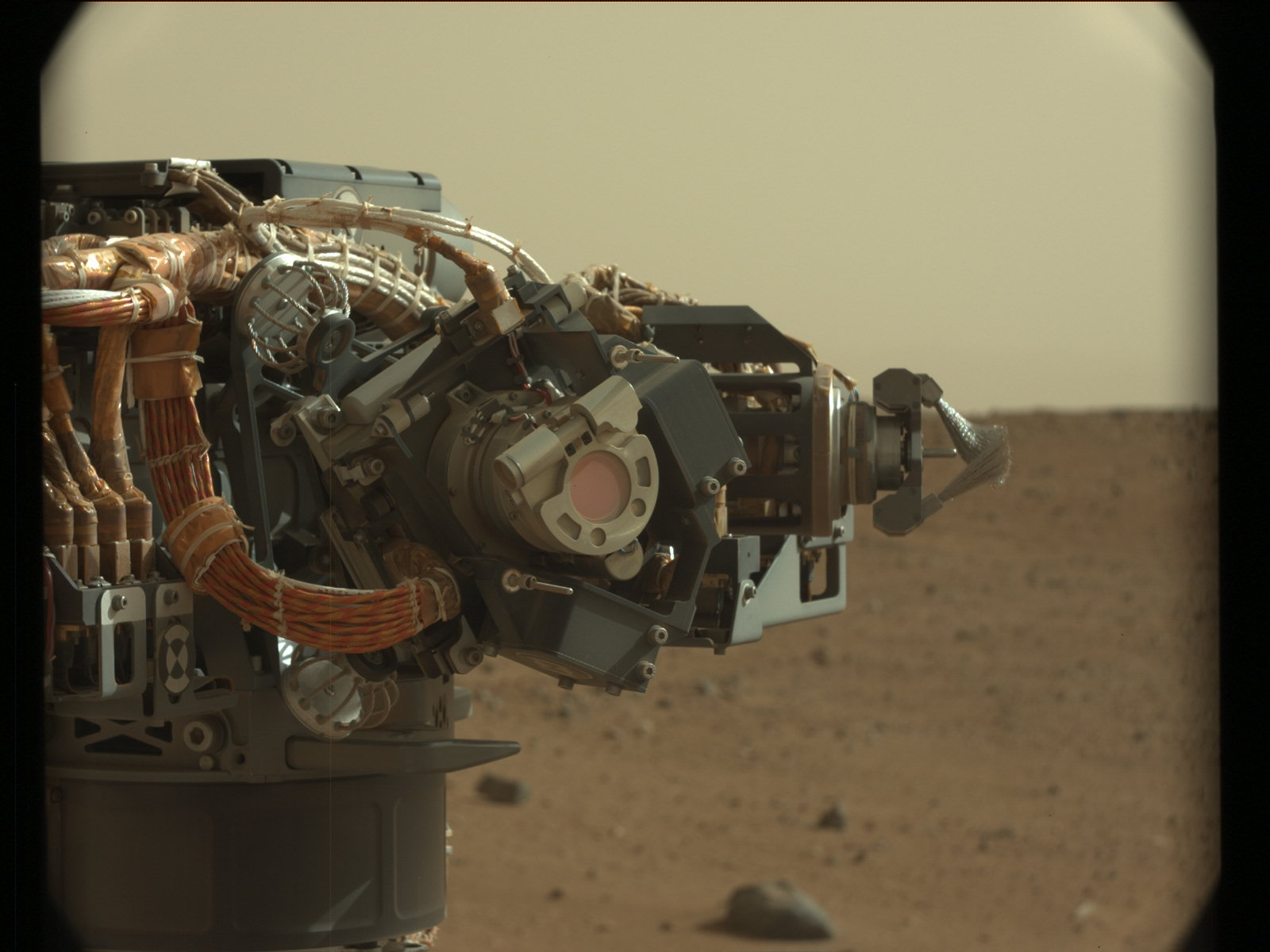

Henderson also uses a camera and specially designed tripod to take pictures of sample materials from 25, 10, 5, and 1 centimeters away, revealing intricate details. This is a lot like what the Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI) camera on NASA’s Curiosity rover does on the Red Planet.

Searching for sulfur

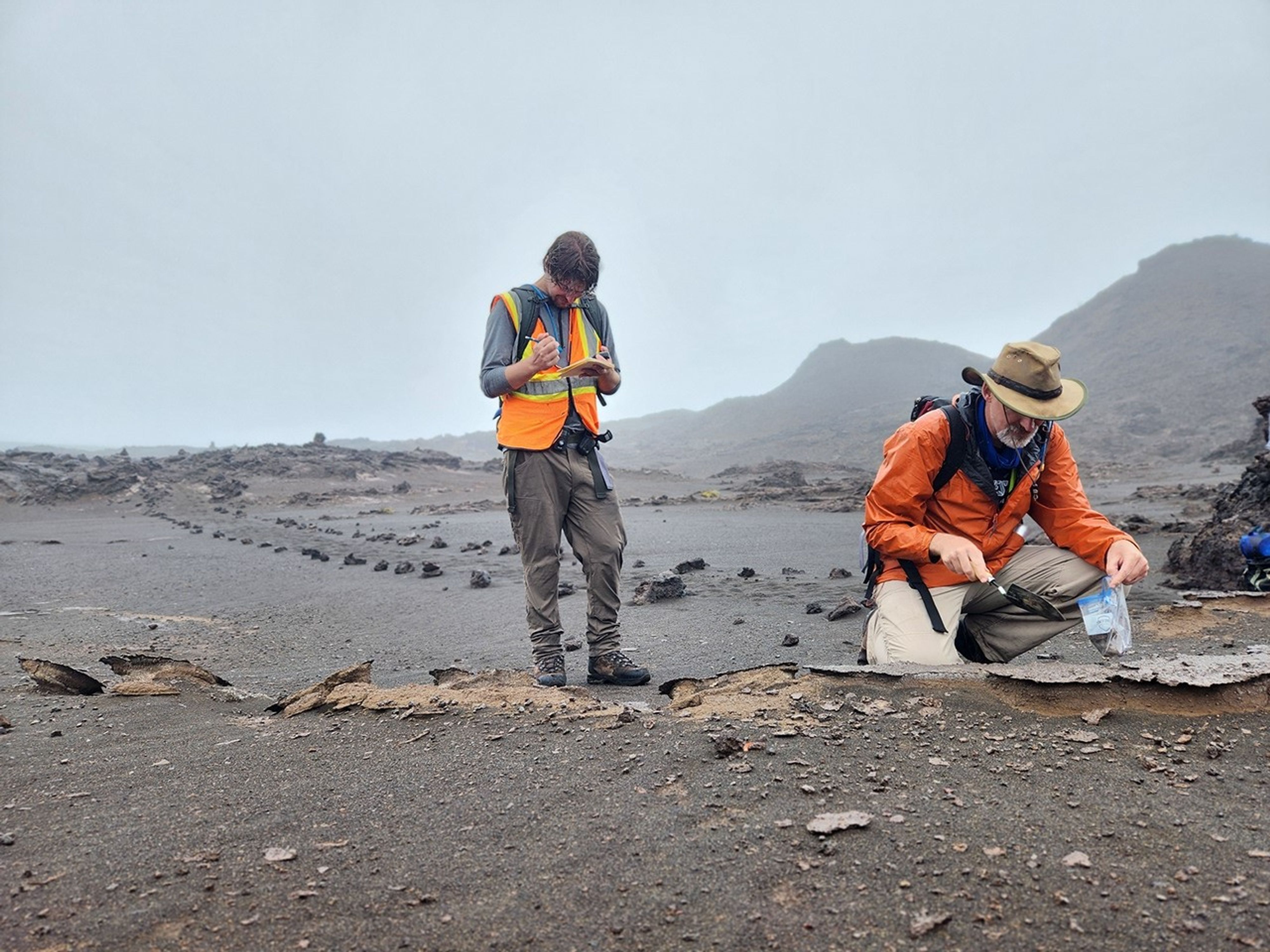

Elsewhere in the National Park, Paul Niles and Justin Hayles of NASA’s Johnson Space Center hike into the Kaʻū Desert, working closely with a National Park Service archaeologist to minimize the impact of their research. They’re trying to understand how sulfur, a fundamental building block of life, changes when it goes through a volcanic eruption.

Sulfur reactions near volcanoes on Earth hold secrets about our planet’s ancient atmosphere. Mars, too, has abundant sulfur from volcanic sources. Our research here will help us understand how to analyze samples returned from the Martian surface.

Mapping Kīlauea Iki

Kīlauea Iki, now a gigantic basalt crater, was once filled with molten lava. Brent Garry and Kat Scanlon of NASA Goddard use a portable laser scanner to make a 3D map of the area, while Ernie Bell (also of NASA Goddard) measures the magnetic field near a hill of volcanic rock.

Their robotic assistant? Lidar — light detection and ranging! It uses millions of tiny laser beams to map the inside of the crater in 3D.

Meanwhile, Bell walks the terrain with a magnetometer collecting evenly spaced lines of data. When this volcanic crater cooled, each landform was left with an invisible magnetic field. Bell’s backpack-mounted detector measures the strength of the field along his path. We’ll compare this volcanic landscape with places on the Moon that may have a similar history.

Revealing invisible patterns with ultraviolet light

Back at the HI-SEAS worksite, Stephen Scheidt and Zach Morse of NASA Goddard capture 360-degree panoramic images and 3D scans of the cave walls. Their first panorama uses white light, so the cave walls appear in their true colors. Next, they’ll take 108 digital photographs to map materials that fluoresce (glow) under ultraviolet light.

The scientists shine ultraviolet light all around the inside of the lava tube, revealing color patterns on the cave wall that are usually invisible to the eye. Other research teams can use these observations to decide where they’ll take samples and look for signs of microbial life.

Scheidt and Morse will use the data they collect to build augmented reality (AR) environments. Imagine entering a cave, opening an AR app on a cell phone, and clicking on each rock to learn about it. Future astronauts may use similar digital tools to help with science decisions on the Moon.

Our Alien Earth: Hawaii

In extreme environments like Hawaii's lava caves, the Goddard Instrument Field Team works to understand life's limits and inform the search for habitable places beyond our planet. Follow the team underground in the latest episode of NASA's Our Alien Earth documentary series.

Watch Now

About Planetary Analogs

Our planet isn't the only place with volcanoes, impact craters, quakes, and erosion. Studying extreme environments on Earth helps us to understand other worlds better, too.

Learn More