Sneak a Peek at the Sun’s Mysterious Atmosphere with a Coronagraph

By Lina Tran and Miles Hatfield

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

NASA’s STEREO spacecraft watches the Sun 24/7 — but the Sun it sees is not the one you and I see.

STEREO can see the Sun’s corona, or outer atmosphere. The only time we can see the corona from Earth with the naked eye is during a total solar eclipse, when the Moon blocks the much brighter photosphere below it.

The corona is a pretty peculiar place — following laws of physics unlike the ones we experience in our day-to-day lives. Somehow, it’s hundreds of times hotter than the Sun’s surface, and scientists don’t know why (this mystery is known as the coronal heating problem). It’s also a minefield of gigantic explosions, like solar flares and coronal mass ejections. These magnetically driven eruptions explode with the energy of a million hydrogen bombs, hurtling hot, electrically charged particles every which way — including towards Earth. Yet for most of human history, we had to wait around for an eclipse to see it.

Then in 1939, Bernard Lyot designed the coronagraph, a tool that created an artificial eclipse inside a telescope. Suddenly, the corona was open for viewing any time.

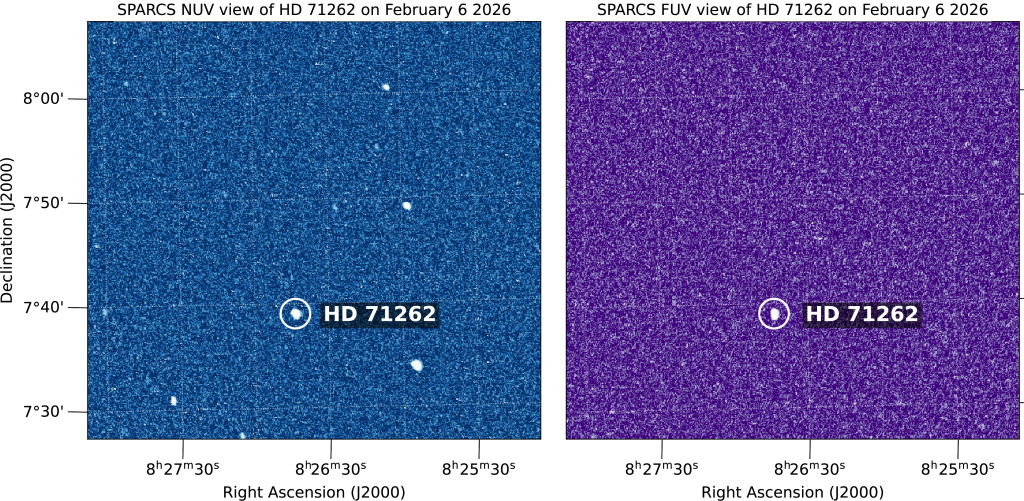

STEREO uses that technology to look at the corona to this day: for example, here’s an image taken by STEREO’s COR2 coronagraph yesterday.

Here’s all you need to know about how coronagraphs work, and what they can tell us about the Sun’s atmosphere.

How they work

Coronagraphs block out bright light from the Sun to reveal the dimmer areas right around it, including the corona, background stars and even passing comets. They do this in two steps. First, an occulting disk at the center of the coronagraph blocks out the photosphere. This gets rid of most of the Sun’s light, but not all — some light gets around it. So that light passes through another special part called a Lyot Stop, named after its inventor, which blocks out even more light towards the edges. That light is then refocused and after a few more corrections, we get an image where almost 99 percent of the Sun’s light has been removed.

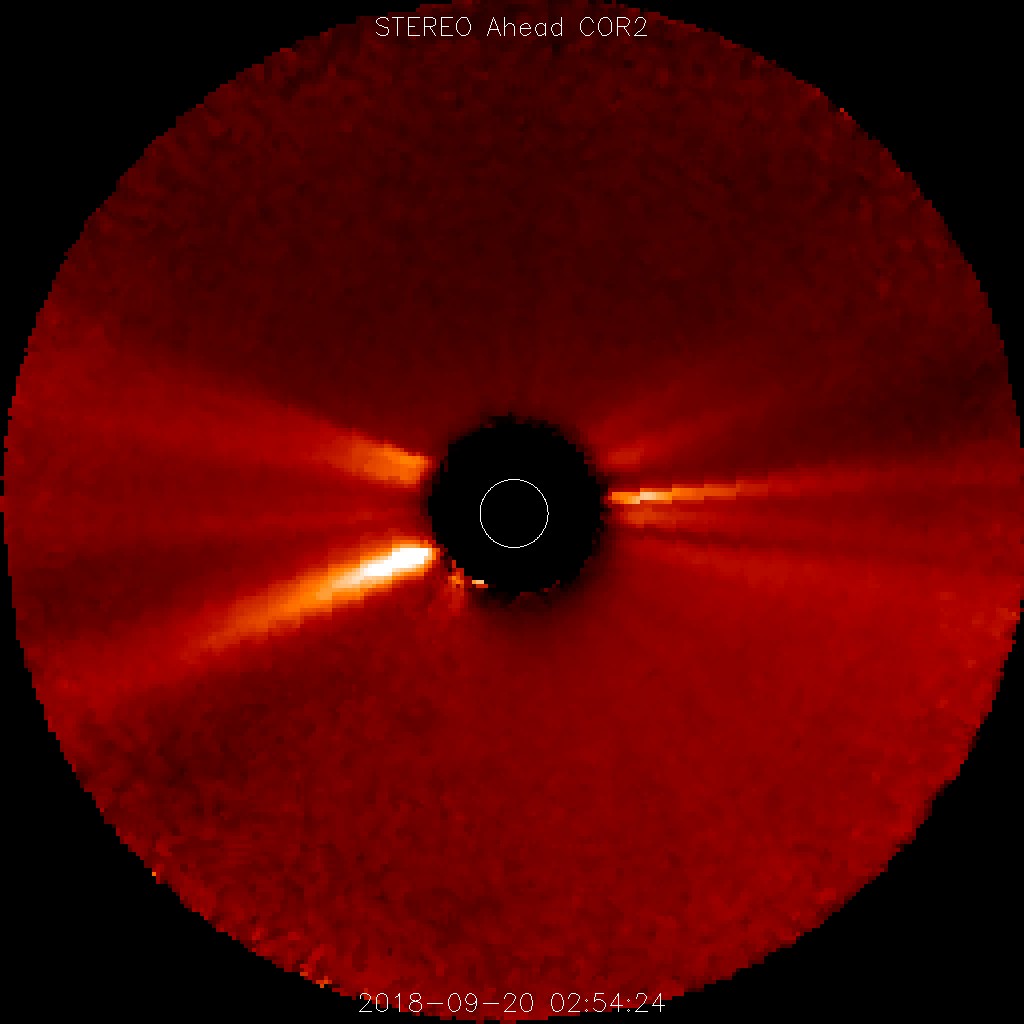

The occulting disk

The black circle in the middle of the image is the occulting disk, which acts like a fake Moon to block out the Sun’s photosphere. In the video above, it has a superimposed image of the Sun from another STEREO instrument, the Extreme UltraViolet Imager-A, on top of it. There are two STEREO spacecraft, and each one has two coronagraphs with occulting disks of different sizes: COR1 shows a part of the corona closer to the surface, from about 1.5 solar radii out to 4 solar radii, whereas COR2 shows the corona out to 15 solar radii. One solar radius is about 432,300 miles.

Blue space

It’s not really all blue out there. STEREO’S coronagraph images are taken in grayscale; false color is added afterwards to help researchers quickly tell which telescope the image is from and to make some features more visually apparent.

Occulting disk pylon

In some coronagraph images, like this one from ESA/NASA’s Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, or SOHO, you can see a dark streak across the image. That’s the shadow of the occulting disk pylon, which holds the occulting disk in place. In other coronagraphs, like STEREO’s COR1, there is no occulting disk pylon — the occulting disk is attached directly to the lens. In yet others like STEREO’S COR2, shown above, the occulting disk pylon is there, but so out of focus that you can’t see it.

Diffraction patterns

Faint ripples around the edge of the occulting disk result from diffracted light. When light enters the telescope, it hits the edge of the metal disk and bends, or diffracts, around the disk.

Coronal streamers

The bright, elongated streams of light jetting out from the disk are called coronal streamers, also known as helmet streamers for their resemblance to a knight’s pointy helmet. Streamers are loops of magnetic field lines that trap electrons within them, which create their bright appearance. The solar wind pushes against coronal streamers, stretching them out to pointy tips, where puffs of plasma can escape to form the solar wind.

Coronal mass ejections

The occasional puffs of material are coronal mass ejections, or CMEs — explosions of solar material being strewn from the Sun. The fastest CMEs can travel over two million miles per hour.

Particle snow

If a CME is directed at a spacecraft, a flurry of what looks like snow floods the image, like in the video shown above. These are high-energy particles flung out ahead of the CME at near-light speeds, striking the camera. The immediacy and intensity of this “snowstorm” reflects just how fast and strong the eruption is: Less than an hour after the start of the eruption shown in the video above, accelerated particles traversed approximately 93 million miles from the Sun to STEREO.

Background stars and comets

With the Sun’s bright light turned to low, you can see much dimmer background stars and comets. At the time of this writing, the STEREO mission has discovered 104 comets and viewed over 150.

Now you’re ready to view the very latest coronagraph images from SOHO and STEREO (scroll down). Keep watch!