6 min read

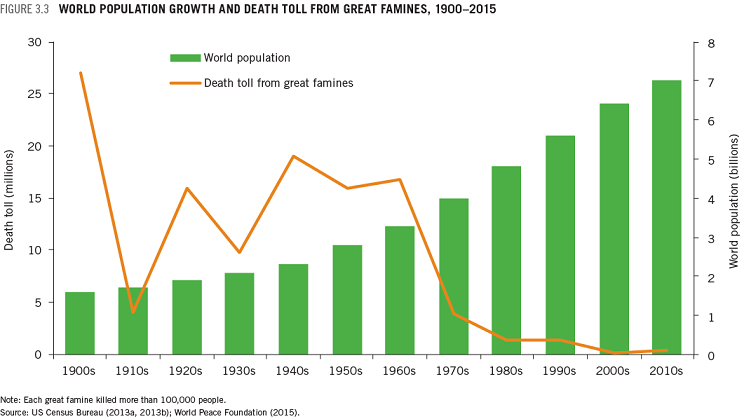

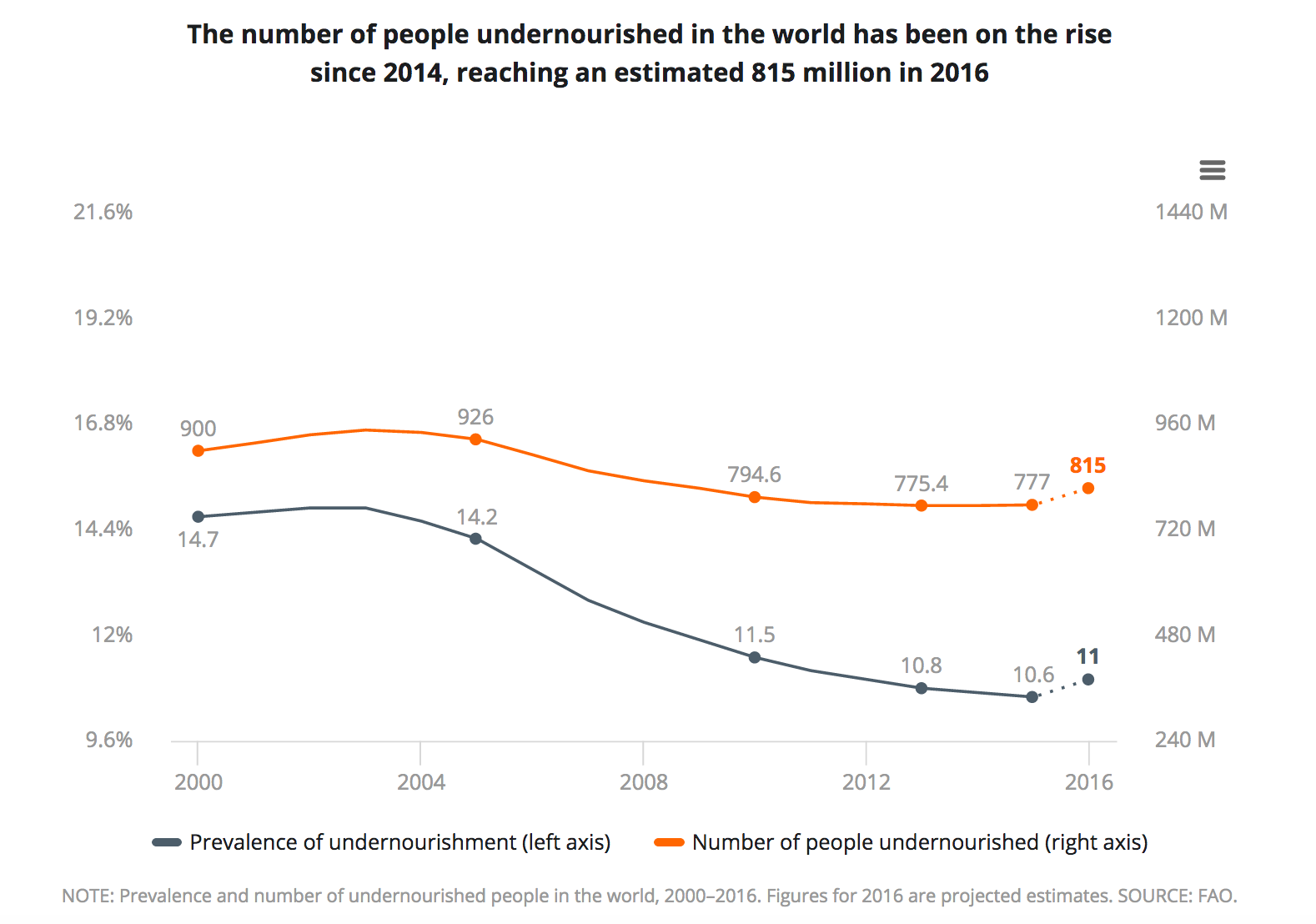

If you take the long view, our world is much better fed than it used to be. In the 1970s, about one-third of people in developing countries were undernourished; today the number is 13 percent. Even as global population has increased, it has been a long time since the horrific famines that claimed 5 million lives or more in the Soviet Union, China, Europe, and India during the 20th Century.

However, serious food shortages remain a fact of life. Roughly 815 million people were undernourished in 2016, according to the UN Food and Agricultural Organization. That is an increase of 38 million people from 2015, making 2016 the first year in more than a decade that the world grew hungrier. The grim trend was driven largely by armed conflicts in South Sudan, Yemen, Nigeria, and Syria.

Meanwhile, other problems loom. Climate change is already starting to exacerbate famines, as temperature and precipitation patterns shift. Many experts worry that food production systems may struggle to adapt in coming decades. Even if problems caused by climate change turn out to be modest, global populations are expected to increase to 10 billion people by 2050, and the demand for food will likely go up by 50 percent or more as people in the developing world increase their income and consume foods that require more resources to produce.

Solving global problems sometimes requires a global view, so NASA’s Applied Sciences Program is working to make sure the world’s food systems are ready for the future. Researchers and program managers have created an agency-wide initiative to put remote sensing data and knowledge into the hands of people who can advance agriculture and reduce world hunger.

Earth Matters sat down with Sean McCartney, the coordinator of NASA’s new Food Security Office, to learn more.

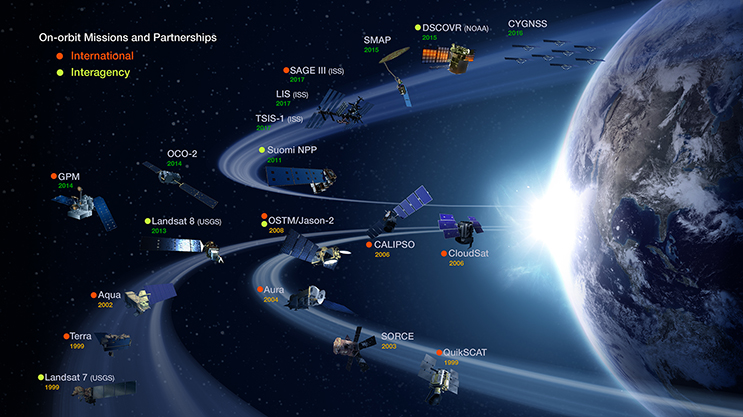

McCartney: People sometimes forget that NASA’s charter states that one of the agency’s key objectives is “the expansion of human knowledge of the Earth and of phenomena in the atmosphere and space.” There are currently around 20 Earth-observing satellites that collect data on the hydrosphere, biosphere, and atmosphere. NASA has been able to leverage this data through scientific analysis and modeling to better understand food systems on a global scale.

The food security initiative is part of our Applied Sciences Program, which does outreach with end users and showcases Earth observations. Through this program, NASA began to work with the United Nations on Sustainable Development Goals (SGDs), a global effort to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure prosperity for all. Some of the goals relate to water and food security, and NASA leadership believed that that was an area where Earth observations could really contribute. Getting involved with the SGDs dovetailed with the establishment of the Food Security Office.

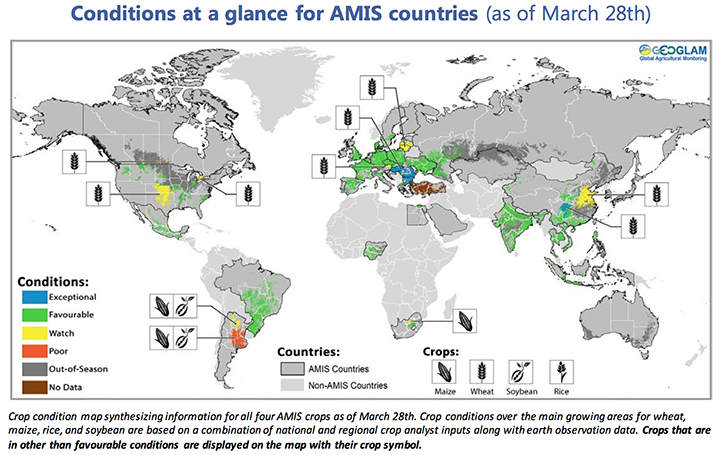

We already do a lot with satellites to monitor major commodity crops like rice, maize, wheat, and soy. We can use satellites to help track key crop characteristics, such as the “greenness” of vegetation (NDVI), crop type, the acreage and distribution of crops, precipitation, soil moisture, evapotranspiration, and more. This sort of environmental data is incorporated into important crop assessment reports, such as the GEOGLAM Crop Monitor, a monthly bulletin on conditions for major crops around the world.

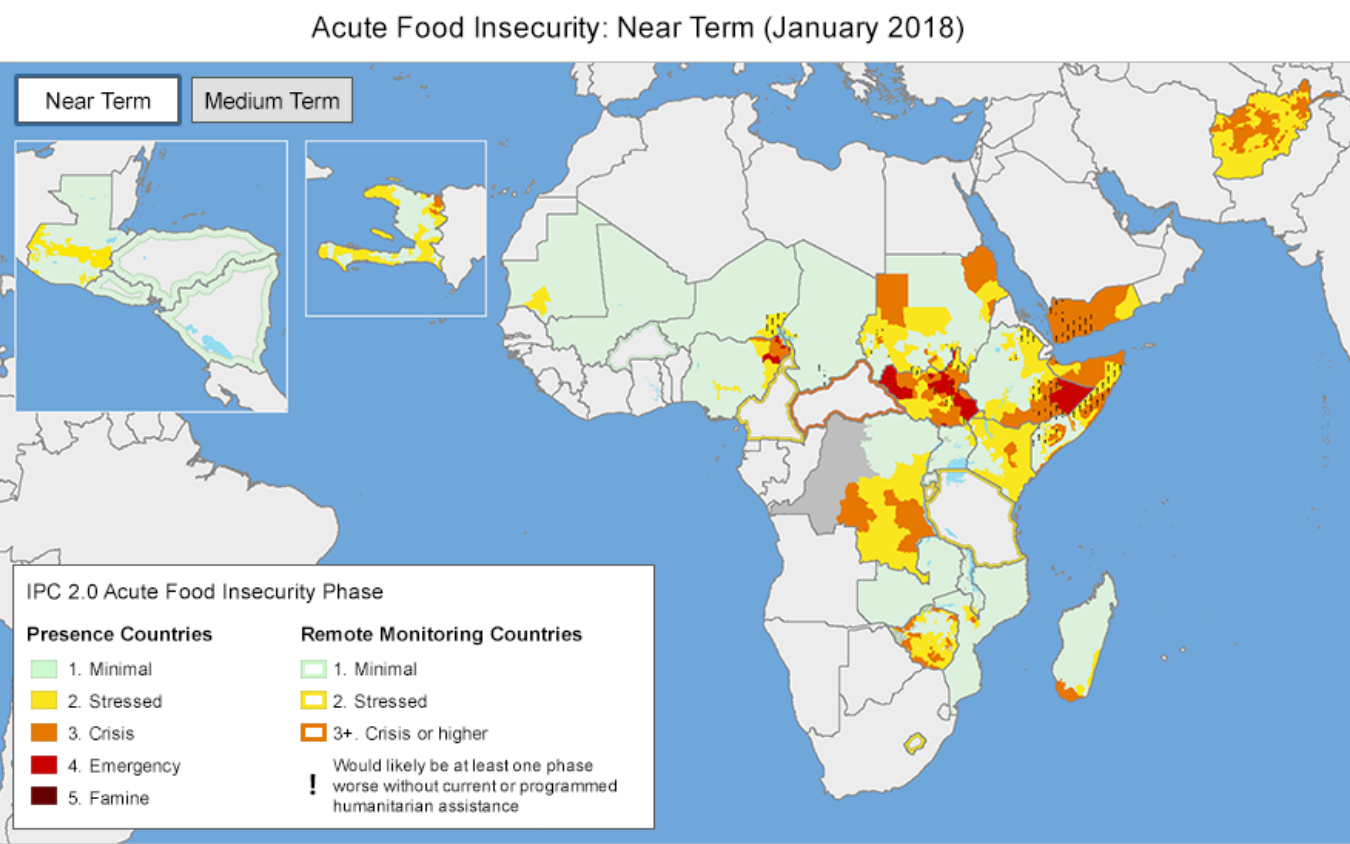

Likewise, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) uses satellite data as part of its Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), which produces frequent reports on food conditions in 34 of the most famine-prone countries in the world.

What we’re trying to do is optimize programs and tools like these — and develop others — and get them into the right hands at the right time. NASA assets help inform governments, NGOs, the private sector, and other stakeholders to anticipate and react to food shortages.

A lot of our efforts so far have been through the Earth Observations for Food Security and Agriculture Consortium (EOFSAC), a program led by the University of Maryland. It really is a multidisciplinary group, which is what makes the program so exciting. The consortium has roughly 40 partner organizations from government, NGOs, international organizations, universities, and the private sector all working together. You can see a full list of the partners here.

Partnering with both the private and public sector—for instance, USDA and USAID—is one focus. They are going to be looking at innovative ways where Earth observations can provide value to end users. That might involve working with the reinsurance industry to provide them with a broad view of crops or working with USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service to develop ways of incorporating more satellite data into their workflow.

In February 2018, the consortium sponsored a workshop at the National Agricultural Library focusing on emerging technologies in Earth observations. Presenters highlighted several new sensors and data sets that are now being applied to agriculture — such as soil moisture, solar induced fluorescence, and satellite-derived precipitation. For a full account of the meeting, you can read the minutes here.

Yes. A lot of what the folks at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies are doing is modeling that assimilates Earth observations into long-term forecasts. They’re studying how climate change will affect crop productivity in the future. There’s an international effort called the Agricultural Model Intercomparison Project (AGMIP) that is focused on this and is a rich source of information.

It really depends on the country. If you look at overall food production, even in countries that are in need, they might be producing adequate food, but they don’t have access to markets, so they can’t get that food to people before it spoils.

Yes, check out @EOFSAC, @GEOCropMonitor, @FEWSNET, @G20_GEOGLAM, and @AgMIPnews.

This piece was originally published on NASA Earth Observatory's Earth Matters blog.