5 min read

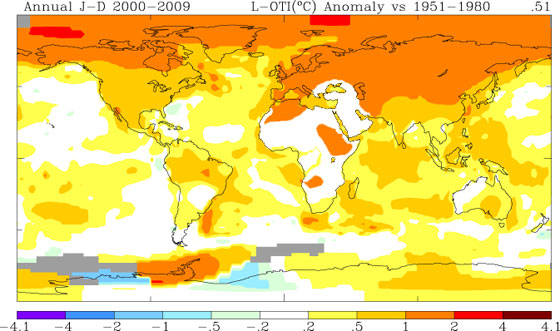

This map, produced by scientists at the Goddard Institute for Space Studies, shows the 10-year average (2000-2009) temperature change relative to the 1951-1980 mean. The largest temperature increases are in the Arctic and the Antarctic Peninsula.

Interview by Adam Voiland,

NASA Earth Science News Team

Dr. Gavin Schmidt, a climate researcher at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) in New York City, studies why and how Earth's climate changes. He spoke to Adam Voiland about the surface temperature record, a dataset that’s generated considerable interest — and some controversy — in the past. GISS updated its surface temperature record with 2009 data this week, and reported that the last decade was the warmest on record.

In fact, for any individual year, the ranking isn't particularly meaningful. The difference in temperature between the second warmest and sixth warmest years, for example, is trivial. The media is always interested in the annual rankings, but whether it’s 2003, 2007, or 2009 that’s second warmest doesn't really mean much because the difference between the years is so small. The rankings are more meaningful as you look at longer averages and decade-long trends.

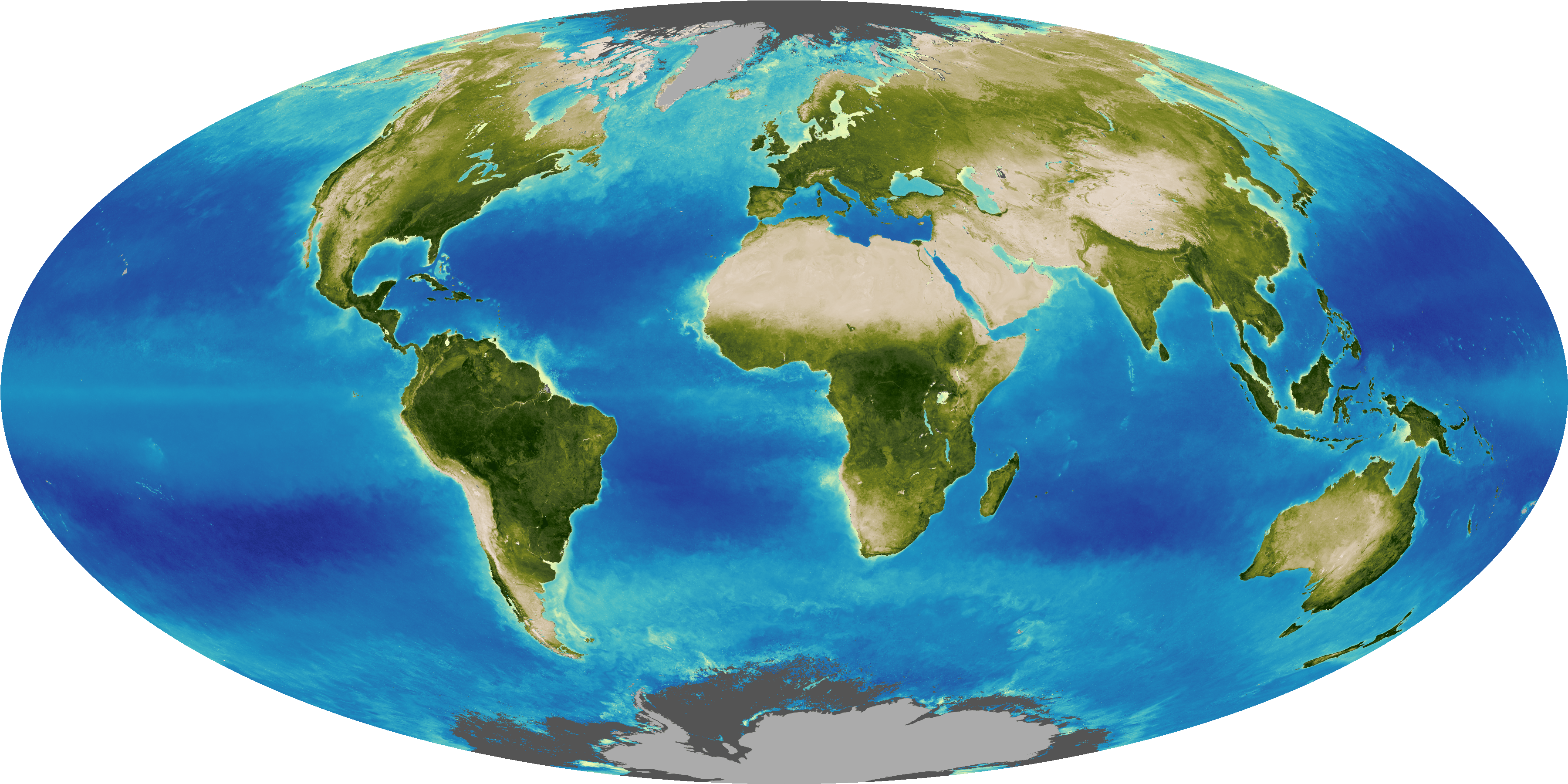

It’s mainly related to the way the weather station data is extrapolated. The Hadley Centre uses basically the same datasets as GISS, for example, but it doesn't fill in large parts of the Arctic and Antarctic regions where fixed monitoring stations don't exist. Instead of leaving those areas out from our analysis, you can use numbers from the nearest available stations, as long as they are within 740 miles (1,200 kilometers). Overall, this gives the GISS product more complete coverage of the Earth’s polar regions.

The assumption involved in this is simply that the Arctic Ocean as a whole is warming at the average of the stations around it. What people forget is that if you don't put any values in for the areas where stations are sparse, then when you go to calculate the mean temperature for the globe, you’re actually assuming that the Arctic is warming at the same rate as the global average. So, either way you are making an assumption.

Which one of those is the better assumption? Given all the changes we’ve observed in the Arctic sea ice with satellites, we believe it’s better to assume the Arctic Ocean is changing at the same rate as the other stations around the Arctic. That’s given GISS a slightly larger warming, particularly in the last couple of years, relative to the Hadley Centre.

No, it doesn't, though you can't dismiss people's concerns and questions about the fact that local temperatures have been cool. Just remember that there's always going to be variability. That's weather. As a result, some areas will still have occasionally cool temperatures — even record-breaking cool — as average temperatures are expected to continue to rise globally. Also keep in mind that that the contiguous United States represents just 1.5 percent of Earth's surface.

Indeed, there are people who believe that GISS uses its own private data or somehow massages the data to get the answer we want. That's completely inaccurate. We do an analysis of the publicly available data that’s collected by other groups. All of the data is available to the public for download, as are the computer programs used to analyze it. One of the reasons the GISS numbers are used and quoted so widely by scientists is that the process is completely open to outside scrutiny.

Global weather services gather far more data than we need. To get the structure of the monthly or yearly temperature changes over the United States, for example, you’d need just a handful of stations, but there are actually some 1,100 of them. You could throw out 50 percent of the station data or more, and you’d get basically the same answers. Individual stations do get old and break down, since they're exposed to the elements, but this is just one of things that NOAA [the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] has to deal with. One recent innovation is the set up of a climate reference network alongside the current stations so that they can look for potentially serious issues on the large scale — and they haven't found any yet.

- Feature Story: "2009: Second Warmest Year on Record; End of Warmest Decade"

- Video: Global Temperature Update 2009

- NASA GISS Surface Temperature Analysis Website

- Raw Station Data

- NASA GISS Surface Temperature Analysis Software Source Code and Documentation

- List of NASA GISS Surface Temperature Analysis References

- U.S. Climate Reference Network