A new analysis of 35 years of meteorological data confirms fire seasons have become longer. Fire season, which varies in timing and duration based on location, is defined as the time of year when wildfires are most likely to ignite, spread, and affect resources.

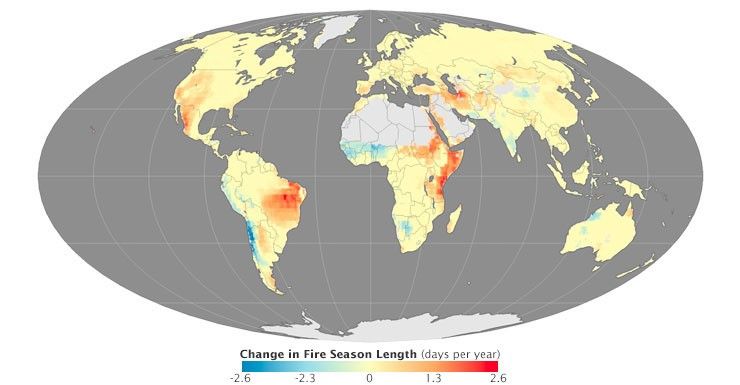

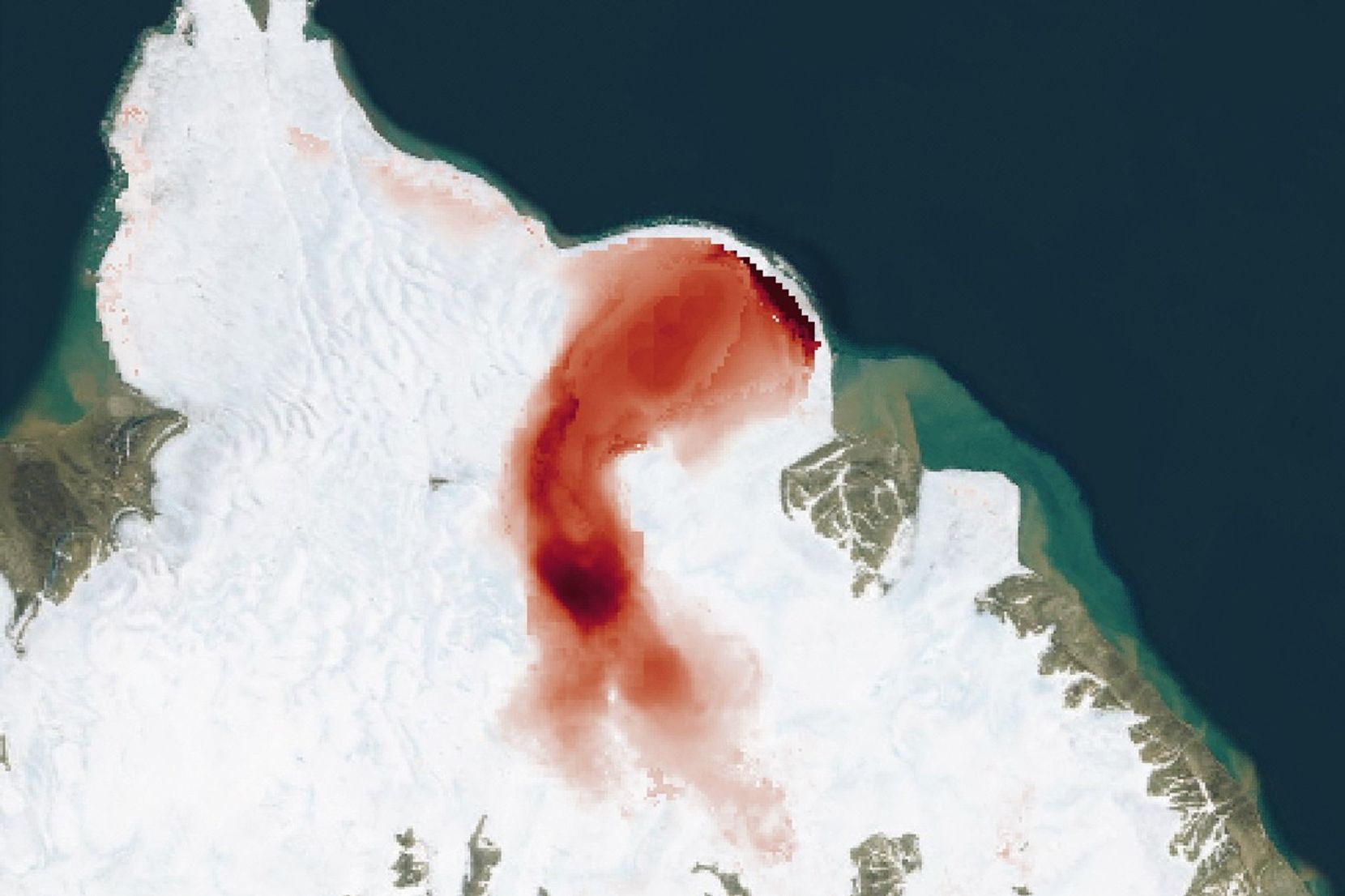

In the map above, areas where the fire season lengthened between 1979 and 2014 are shown with shades of orange and red. Areas where the length of the fire season stayed the same are yellow. Shades of blue show where the fire season grew shorter. Gray indicates that there was not enough vegetation to sustain wildfires.

The analysis, led by U.S. Forest Service ecologist Matt Jolly, focused on four meteorological variables that affect the length of fire season: maximum temperatures, minimum relative humidity, the number of rain-free days, and maximum wind speeds. A combination of high temperatures, low humidity, rainless days, and high winds make wildfires more likely to spread and lengthens fire seasons. Jolly and colleagues used data from NOAA’s National Center for Environmental Prediction Reanalysis, NOAA’s NCEP-DOE Reanalysis, and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Interim Reanalysis.

The researchers found that fire weather seasons have lengthened across one quarter of Earth’s vegetated surface. In certain areas, extending the fire season by a bit each year added up to a large change over the full study period. For instance, parts of the western United States and Mexico, Brazil, and East Africa now face wildfire seasons that are more than a month longer than they were 35 years ago.

The authors attribute the longer season in the western United States to changes in the timing of snowmelt, vapor pressure, and the timing of spring rains—all of which have been linked to global warming and climate change. On the other hand, the easing of droughts in Western Africa and the Pacific coast of South America likely contributed to the shortening of fire seasons in those areas.

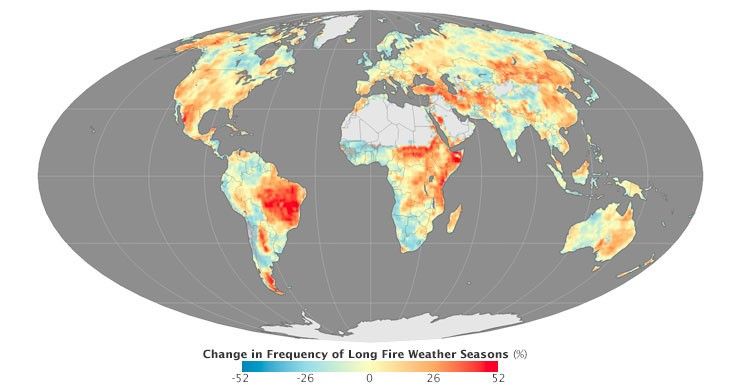

In some parts of the world, tough fire seasons have also become more frequent. “The map at the top of the page depicts steady trends in season length, while the map below shows changes in variability,” explained Jolly. “In other words, the map below shows where long seasons are becoming more frequent, even if they aren’t becoming steadily longer.”

While many of the same areas that saw fire seasons grow progressively longer also faced more frequent fires seasons, the two measures differed significantly in some areas. Australia, for instance, has not experienced an increase in the length of fire seasons. However, eastern Australia has seen the years with long and severe fire seasons become more frequent.

Overall, 54 percent of the world’s vegetated surfaces experienced long fire weather seasons more frequently between 1996 and 2013 as compared with 1979-1996, according to Jolly. This amounted to a doubling in the total global burnable area affected by long fire weather seasons. (For this calculation, “long fire season” was defined as a length that was one standard deviation above the historical mean.)

It is important to note that although the study shows many environments have become more prone to fires, it does not demonstrate that the wildfires burned more intensely or charred more acres. That’s because even with longer and more frequent fire seasons, other factors can affect whether fires occur and how they behave, such as: whether lightning or human activity ignites the fires; whether humans attempt to suppress them; and whether there is enough fuel to sustain them.

References

- Jolly, M. et al, (2015, July 14) Climate-induced variations in global wildfire danger from 1979 to 2013. Nature Communications, (6) 7537.

Further reading

- Scientific American (2015, July 14) More Wildfires Burning More Forest May Become the New Normal. Accessed July 21, 2015.

- The Washington Post (2015, July 15) Scientists say the planet’s weather is becoming more conducive to wildfires. Accessed July 21, 2015.

- Missoulan (2015, July 20) Missoula study: Climate change increasing length of wildfire seasons worldwide. Accessed July 21, 2015.

This article was reposted from NASA's Earth Observatory.