Lately, it feels like we’re hearing about wildfires erupting in the western United States more often. But how have wildfire occurrences changed over the decades?

Researchers with the NASA-funded Rehabilitation Capability Convergence for Ecosystem Recovery (RECOVER) have analyzed more than 40,000 fires from Colorado to California between 1950 to 2017 to learn how wildfire frequency, size, location, and a few other traits have changed.

Here are six trends they have observed in the western United States:

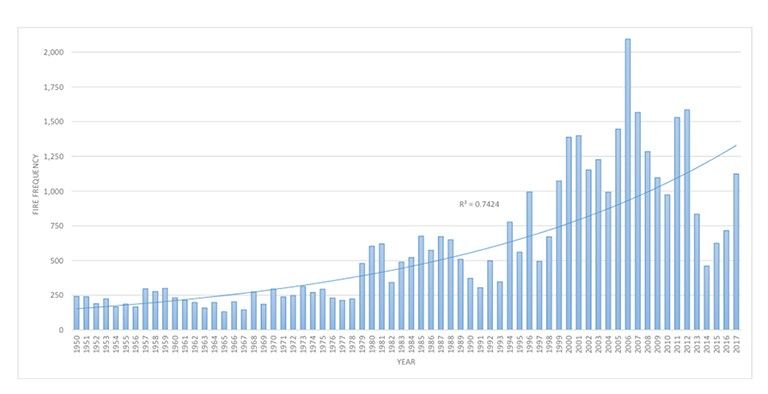

1. There are more fires.

Over the past six decades, there has been a steady increase in the number of fires in the western U.S. In fact, the majority of western fires—61 percent—have occurred since 2000 (shown in the graph below).

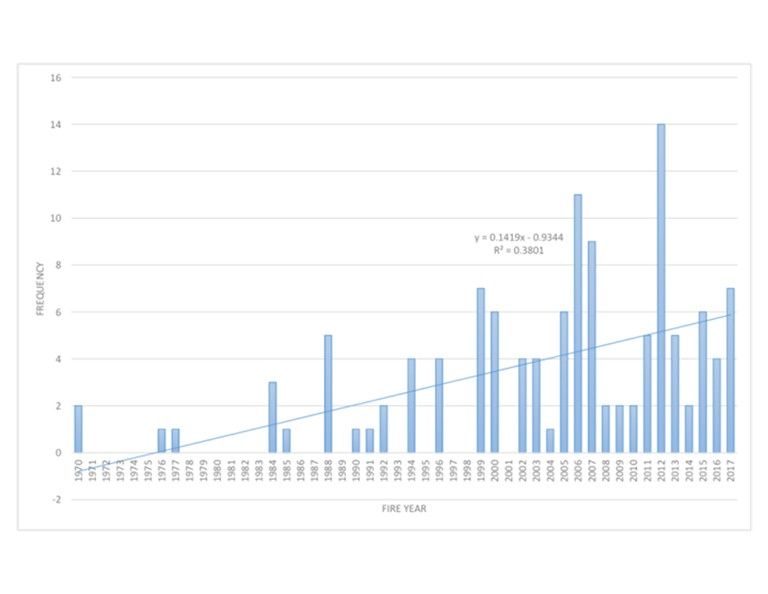

2. And those fires are larger.

Those fires are also burning more acres of land. The average annual amount of acres burned has been steadily increasing since 1950. The number of megafires—fires that burn more than 100,000 acres (156 square miles)—has increased in the past two decades. In fact, no documented megafires occurred before 1970.

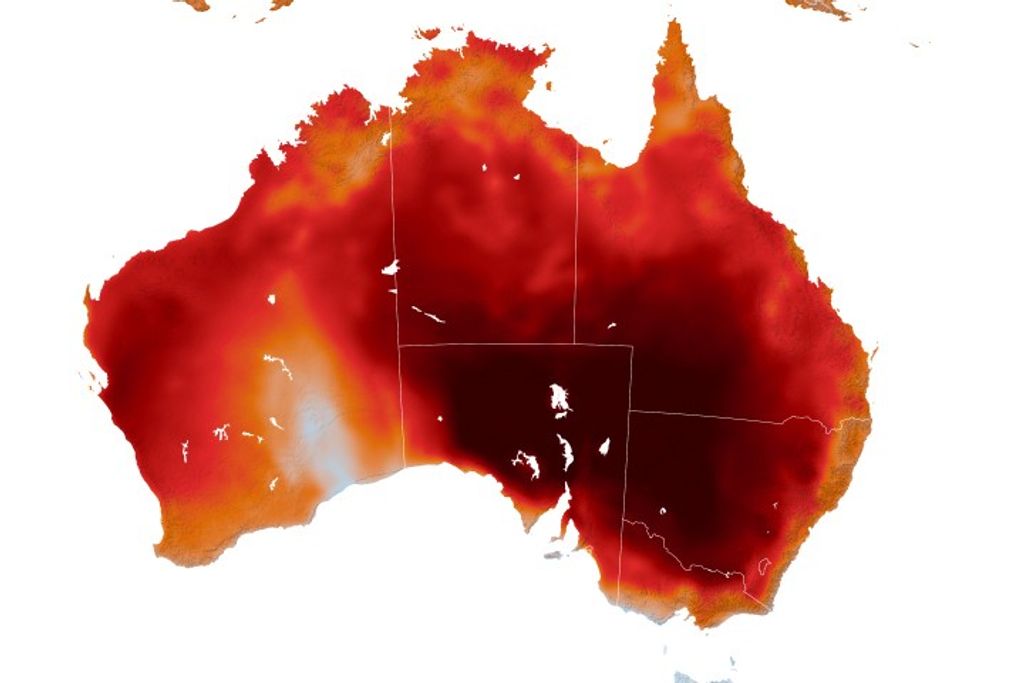

The recent increase in fire frequency and size is likely related to a few reasons, including the rise of global temperatures since the start of the new millennia. Seventeen of the 18 warmest years on record have occurred since 2001.

Global temperatures can affect local fire conditions. Amber Soja, a wildfire expert at NASA’s Langley Research Center, said fire-weather conditions—high temperatures, low relative humidity, high wind speed, and low precipitation—can increase dryness and make vegetation in the west easier to burn. “Those fire conditions all fall under weather and climate,” Soja said. “The weather will change as Earth warms, and we’re seeing that happen.”

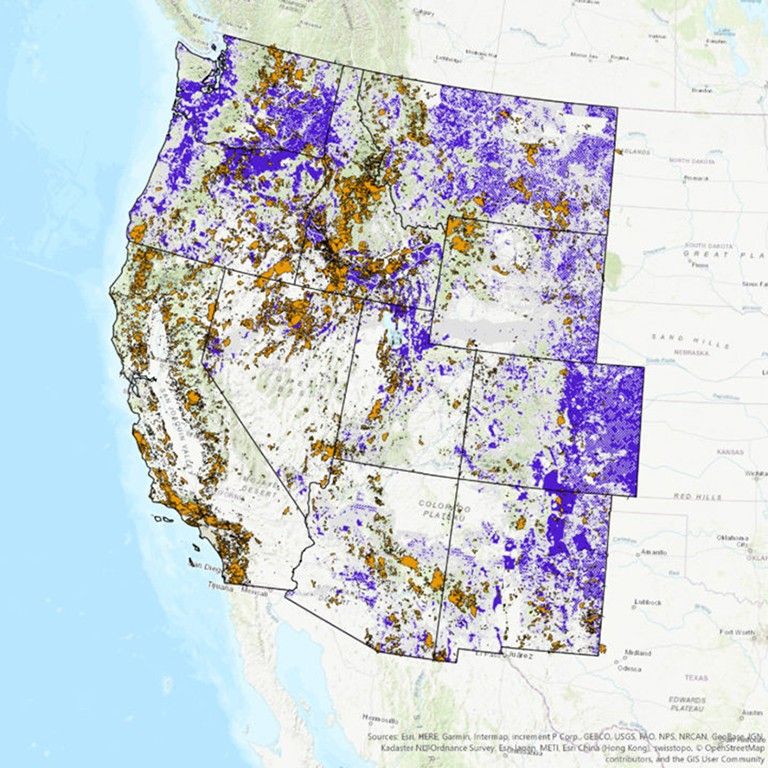

3. A small percentage of the West has burned.

Even though fire frequency and size has increased, only a small percentage of western lands— 11 percent—has burned since 1950. In this map, wildfires are shown in orange. Private lands are shown in purple while public lands are clear (no color). The location of wildfires was random; that is, there was no bias toward fires affecting private or public land.

Keith Weber, a professor at Idaho State University who led the analysis, was surprised at the 11 percent figure. There’s no clear reason yet for why more of the region hasn’t burned. “Some of the 89% may not burn because it has low susceptibility—not dry enough or it has low fuel (vegetation),” said Weber. “Some areas may be really ripe for a fire, but they have not had an ignition source yet.”

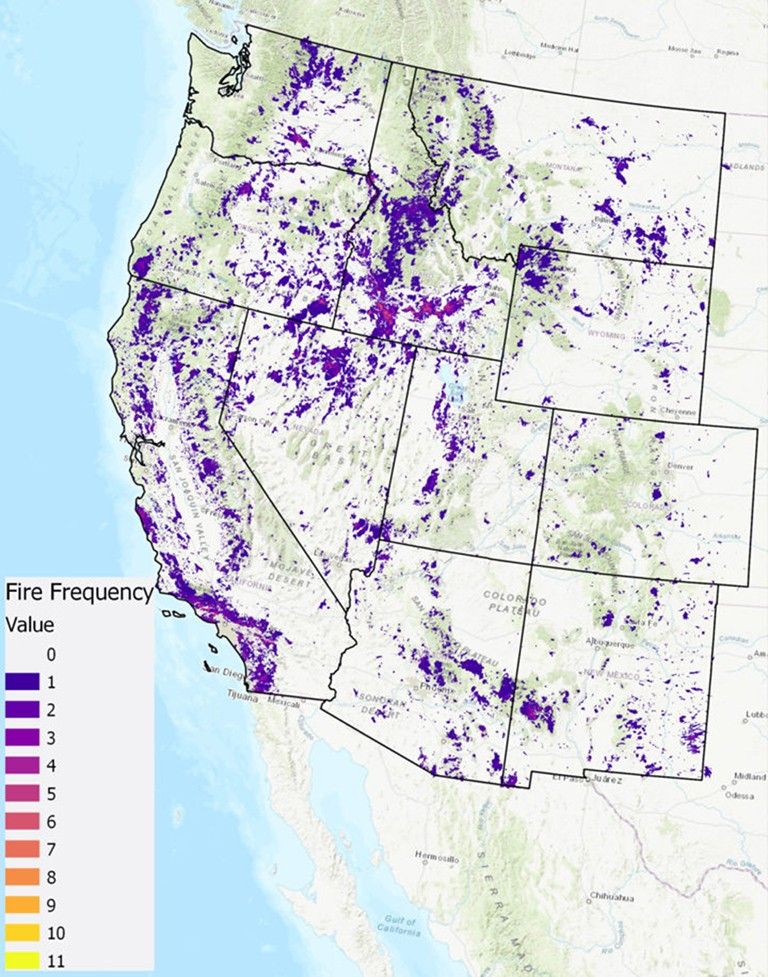

4. The same areas keep burning.

How has only 11 percent of the west burned, yet the annual number of acres burned and the frequency of fire increased? It turns out that many fires are occurring in areas that have already experienced fires, known as burn-on-burn effects. About 3 percent—almost a third of the burned land—has seen repeated fire activity.

The map here shows the locations of repeated fire activity. While you can’t see it at this map’s resolution, some areas have experienced as many as 11 fires since 1950. In those areas, fires occurred about every seven years, said Weber, which is about the amount of time it takes for an ecosystem to build up enough vegetation to burn again.

5. Recent fires are burning more coniferous forests than other types of landscape.

Since 2000, wildfires have shifted from burning shrub-lands to burning conifers. The Southern Rocky Mountains Ponderosa Pine Woodland landscape has experienced the most acres burned—more than 3 million.

The reason might lie within the tree species. Ponderosa Pine is a fire-adapted species. With its thick and flaky bark, the tree can withstand low-intensity surface fires. It also drops branches lower as they age, which deters fire from climbing up the tree and burning their green needles. “The fire will remove forest undergrowth, but will be just fine for the pines,” said Weber. “We are starting to see Ponderosa Pines thrive in those areas.”

6. Wildfires are going to have a big impact on our future.

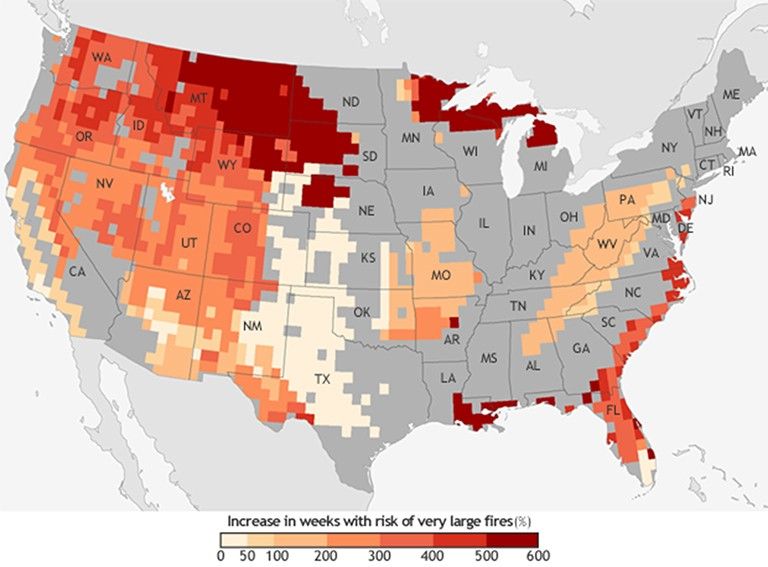

Research suggests that global warming is predicted to increase the number of very large fires (more than 50,000 acres) in the western United States by the middle of the century (2041-2070).

The map below shows the projected increase in the number of “very large fire weeks”—periods where conditions will be conducive to very large fires—by mid-century (2041-2070) compared to the recent past (1971-2000). The projections are based on scenarios where carbon dioxide emissions continue to increase.

According the Fourth National Climate Assessment, wildfires are expected to affect human health and several industries:

- Wildfires are expected to further stress our nation’s “aging and deteriorating infrastructure.”

- Smoke from wildfires is expected to impair outdoor recreational activities.

- Wildfires on rangelands are expected to disrupt the U.S.’s agricultural productivity, creating challenges to livestock health, declining crop yields and quality, and affecting sustainable food security and price stability.

- Increased wildfire activity is “expected to decrease the ability of U.S. forests to support economic activity, recreation, and subsistence activities.”

More about the source data:

Unless otherwise stated in the article, these data come from NASA’s Rehabilitation Capability Convergence for Ecosystem Recovery. RECOVER is an online mapping tool that pulls together data on 26 different variables useful for fires managers, such as burn severity, land slope, vegetation, soil type, and historical wildfires. In the past, fire managers might need several days or weeks to assemble and present such a large amount of information. RECOVER does so in five minutes, with the help of sophisticated server technologies that gather data from a multitude of sources. Funded by NASA’s Applied Science Program, RECOVER provides these data on specific fires to help fire managers to start rehabilitation plans earlier and implement recovery efforts quickly.

The researchers used the data layer showing historical fires since 1950, which were compiled from comprehensive databases by the U.S. Geological Survey Geospatial Multi-Agency Coordination, National Interagency Fire Center, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, and various state agencies such as the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. The historical fires do not include prescribed fires and undocumented fires. Learn more about the RECOVER program and its recent involvement with the Woosley Fire.

The piece was originally published on the NASA Earth Observatory "Earth Matters" blog.