Sometimes a story about a NASA volunteer just grabs your heart and won’t let go. NASA Scientist Dr. Brian Day shared with us the incredible story of what first ignited his passion for involving the public in his scientific research. It’s a story about a boy named Amaey Shah.

“Through the NASA Speakers Bureau, I was paired with a local teacher, Leslie Herleikson, and her after-school science program for K-12 students” Brian began. “I’d talk to the students in the program periodically and take them on tours of the NASA Ames facilities.”

“One of the kids in Leslie’s elementary program, a young boy named Amaey Shah, was recovering from treatment for childhood leukemia when I first met him. He was feeling fatigued from the treatment. As we did the tours of Ames he sometimes had to rest. But he was a very precocious kid. He remained very excited about science, posing a rapid stream of very insightful questions, and always full of joyous enthusiasm for the new things that he would learn.

Over time, Amaey rallied and his strength improved, fueled by his insatiable curiosity. I continued to meet with Amaey and his fellow students, with our discussions spanning the Solar System and beyond.

Then, one day, I showed up at the after-school program and Amaey was not there. Leslie took me aside after my presentation and let me know that Amaey had had a relapse which seemed pretty serious. He was going to need a bone marrow transplant. This news hit me especially hard. Shortly before the class meeting, I had been diagnosed with cancer myself. Just as Amaey was going to be heading in for whole body radiation as part of his bone marrow transplant, I was going to be going in for radiation for my own cancer treatment.

Leslie shared my situation with Amaey and his parents. She also asked if I would be willing to come talk with him about our upcoming shared experience. The idea seemed strangely comforting and healthy. So I showed up at his house. Amaey and I sat down together, with his parents and older brother sitting off to the side in the same room.

I said: Well, I understand we have something in common.

He said, Well, we both like science!

I said: That’s true.

He said: And we both wear glasses.

I said: Yes.

Then, I said: And we’re both incredibly handsome!

We all had a good laugh. But then he looked at me and got serious.

He said: And we both have cancer.

I said: Yes, and we’re both going to get radiation.

And he said: Yeah.

So I said: How do we feel about that?

He told me what was bothering him most. He said that in his case, the radiation was to kill all of his bone marrow, and hopefully the cancer that was within it. Then he would get a transplant of new bone marrow. But during the period of time in between losing his old bone marrow and when his new bone marrow kicked in, he would essentially be without an immune system. He would become a bubble boy—confined to a room for a very long period of time. He expressed that he was really going to miss going out and exploring, going out and looking up at the night sky, because one of the things he really, really wanted to do was explore space.

I’d been given a warning about this from his parents, so I’d come prepared with my laptop. I pulled up MoonZoo. MoonZoo was a citizen science application that asked people to look at pieces of lunar real estate and identify and count craters. Crater counts are the primary way of estimating the ages of various lunar terrains. If we want to understand the history and evolution of the lunar surface, getting these crater counts and the ages they represent is a really critical endeavor.

Amaey was quite excited to work on MoonZoo. We played with that for a long while! Then I pulled up GalaxyZoo, another Zooniverse project.

We reviewed the fact that galaxies come in a great variety of sizes and shapes. And we see a mind-bending number of galaxies out there. To understand their formation and evolution, we must first understand what kinds of galaxies they are. So, we need people to help classify these galaxies---which involves looking at a lot of galaxies. Amaey really liked that too.

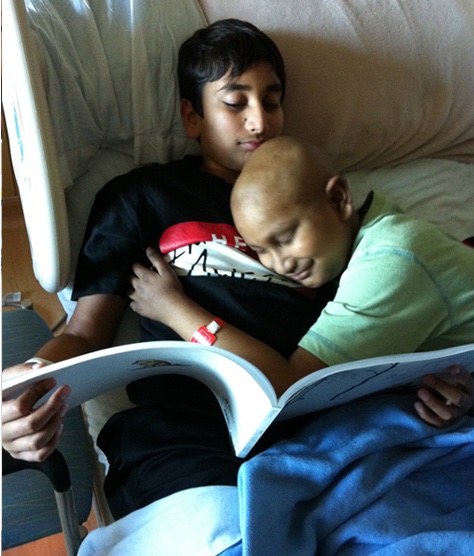

We went into our respective cancer treatments. Amaey did indeed become confined in isolation after his irradiation and transplant---but I heard from his teacher Leslie that from his room he was keeping himself busy exploring the Moon, counting craters with MoonZoo, and classifying galaxies with GalaxyZoo. Even though Amaey was physically confined to his room, his intellect and curiosity were free to roam the Solar System and the Universe, exploring limitless expanses, thanks to the citizen science tools that he put to such good use. Soon, I got distracted with my own treatment, and I wasn’t online as much as I would have liked to have been.

As I was going through my own treatment, I didn’t get the news. Amaey’s treatment didn’t work. His parents and teachers opted not to tell me that he had passed away while I was in the midst of fighting my own battle.

The day after I successfully finished my final radiation treatment, I remember talking to Leslie on the phone. I told her that I was done, and I wanted to come talk to the kids again as soon as I was feeling a bit stronger. She said she had something to tell me. She let me know that Amaey had passed away. I was devastated.

Leslie also told me that Amaey’s funeral service was coming up soon. Amaey’s parents then contacted me, asking me if I might be feeling well enough to come speak at the service. I had to go. There was no way I could not be there!

There were many people gathered together at the service and several speakers. At one point, Amaey’s grandfather got up and in a quiet, sorrowful way, explained how Amaey’s desire had always been to be a scientist. Amaey had wanted to study the stars, do research, and contribute. One of the great sadnesses of the grandfather’s own life was that Amaey never had the opportunity to become a scientist, to explore the Universe, and to contribute to the science like he had so loved.

Then it was my turn to speak. I stood up, and I said that I mean no disrespect---I fully understood the sorrow that the family was feeling. But the very important fact of the matter was that Amaey did not miss this opportunity! Amaey HAD realized his dream. He DID become a scientist. From his isolation room, Amaey DID explore. He DID do research. He DID make contributions. Amaey’s ambitions had been realized, and his discoveries had been added to the scientific record.

I said we can all take heart in knowing that under very difficult circumstances Amaey had achieved his dream. That seemed to become a source of comfort to Amaey’s family. And that’s because he stepped up to the role and adventure of being a citizen scientist.”

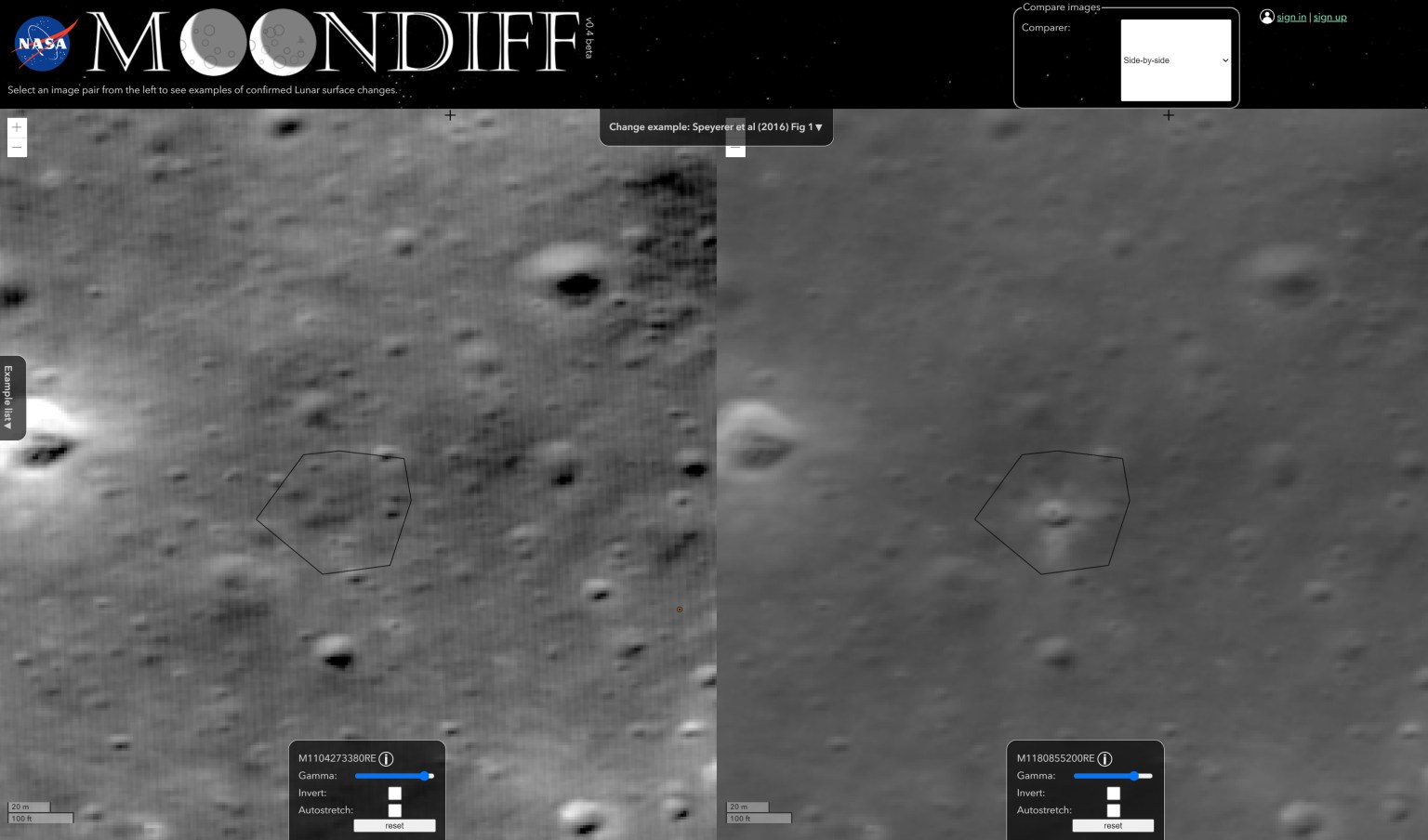

Brian Day is the staff scientist at NASA’s Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute, headquartered at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California. His duties include serving as science lead for NASA’s Solar System Treks Project a family of open science online portals that make it easy to analyze the surfaces of the Moon and other planetary bodies in our Solar System. The project has a citizen science component called MoonDiff, which invites you to help search for changes and newly formed features on the Moon.

You can make your own contributions to science! Check out Brian’s project, MoonDiff. And if you know any other children like Amaey, please share it with them.