Introduction

Every day, all over the world, enthusiastic amateurs are making discoveries and valuable contributions to science—no fancy degrees or resumes needed. From a 15-year-old in Connecticut studying exoplanets to a furniture seller in the Philippines processing images of Jupiter at night, we’re shining the spotlight on how citizen science is helping us understand our universe.

1. The world of citizen science

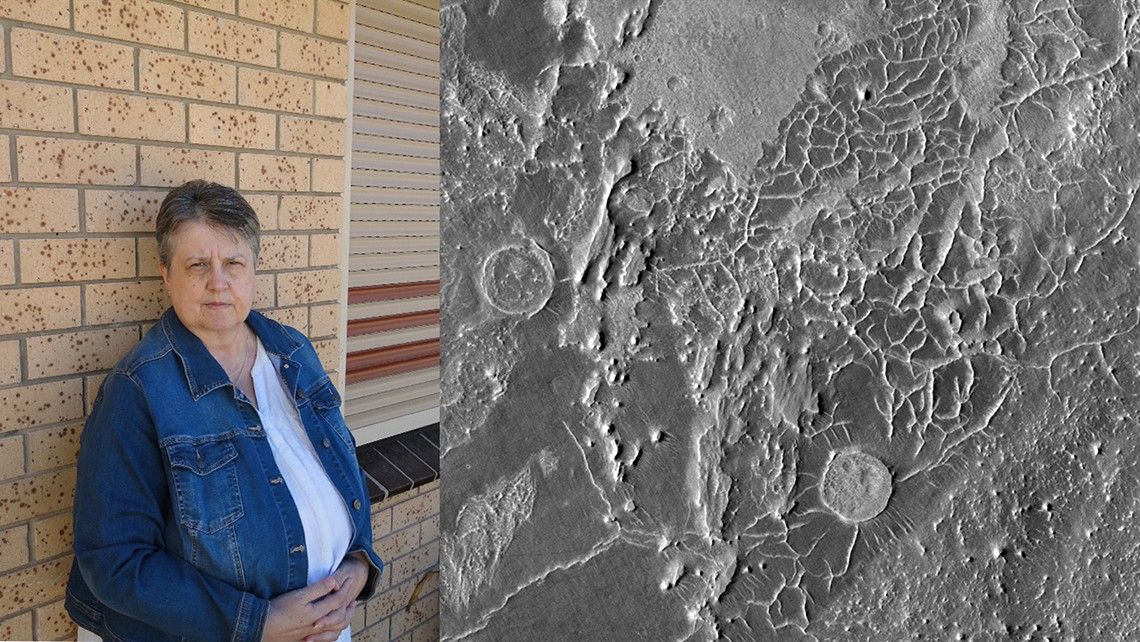

From Earth to Mars to beyond our Solar System, thousands of people worldwide participate in “citizen science” initiatives using NASA data that anyone, regardless of education or background, can use for real scientific research. We followed their journeys, beginning with Sylvia Beer, a 61-year-old woman with Parkinson’s disease studying ridges on Mars.

2. Day in the life

In Cebu, Philippines, Christopher Go wakes up at 3 a.m. (yes, you read that right) to start imaging Jupiter with his telescope before heading off to his day job selling furniture.

3. Purpose, found

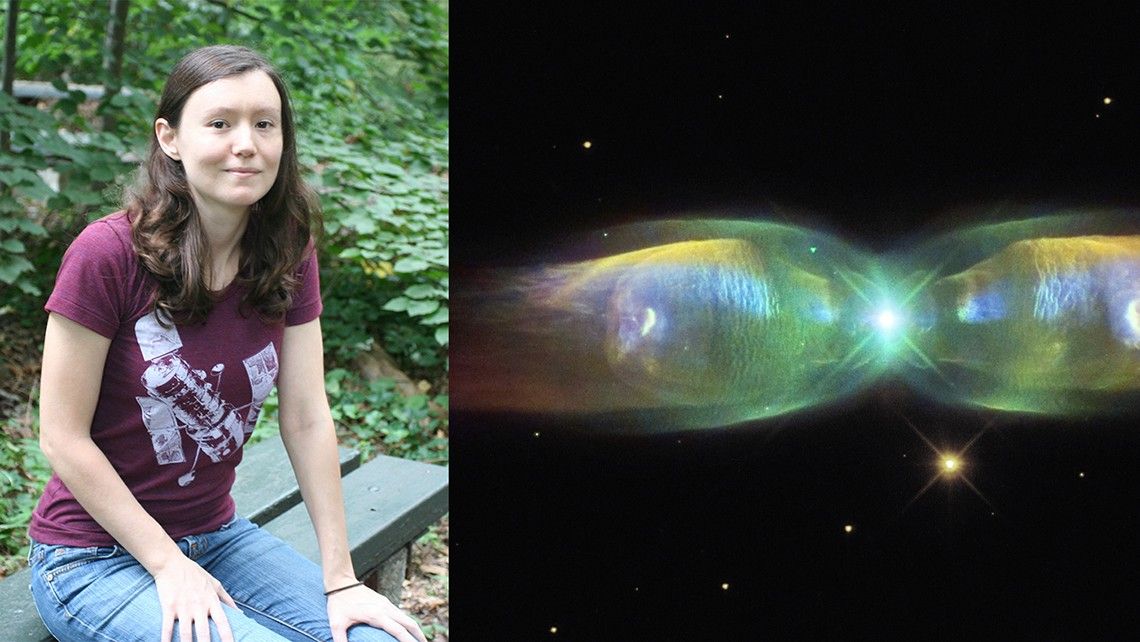

Judy Schmidt moved to New York City to be with her husband but found herself without a job in a strange new city, “bored and depressed,” as she puts it. So she decided to learn about astronomy. “I got into citizen science partly because I felt worthless and was looking for purpose.” Now, she processes spectacular images using NASA data.

4. And spacecraft found

Amateur astronomer Scott Tilley made an amazing discovery: He found a lost NASA spacecraft that had been missing since 2005 - NASA's IMAGE spacecraft.

5. From citizen scientist to NASA

Ocean McIntyre lost most of her vision to a rare neurological disorder. “My life as I knew it came to a screeching half. I had to get acclimated to life without a fully functioning brain and eyes,” she recalls. “At the same time, my disability forced me to appreciate the beauty of the sky and space even more, and I became even more inspired to make a difference in space science.” She went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in planetary science and astronomy three years ago. As of December 2017, she’s now on the Europa Clipper mission team. Read her full story.

6. Age is just a number

Alton Spencer was a 15-year-old high school sophomore in Connecticut when he started spending his free time looking for exoplanets. “I don’t feel like there’s an age restriction when it comes to making great discoveries,” he says. “Citizen science is a way for people in middle or high school, like me, to actually make contributions to science despite not being in college or having science careers yet.” Read Alton’s full Q&A.

7. Those who made history

Citizen science has been around for centuries. For example, Anna Atkins, a 19th century English botanist, laid the groundwork for scientific books illustrated with photography. She created cyanotypes, images made by placing objects directly onto light-sensitive paper.

8. Mysterious Steve

There were normal auroras—entrancing light shows in the sky caused by charged particles from the Sun interacting with Earth's magnetic field—and then there were the thin purple ribbons of light no one could explain. From 2015 to 2016, citizen scientists shared 30 reports of these mysterious lights in online forums and with a team of scientists running a project called Aurorasaurus. A study points out that the phenomenon, nicknamed STEVE, may be an extraordinary puzzle piece in our understanding of how Earth's magnetic fields interact with charged particles in space. More on citizen science discoveries.

9. Head in the clouds

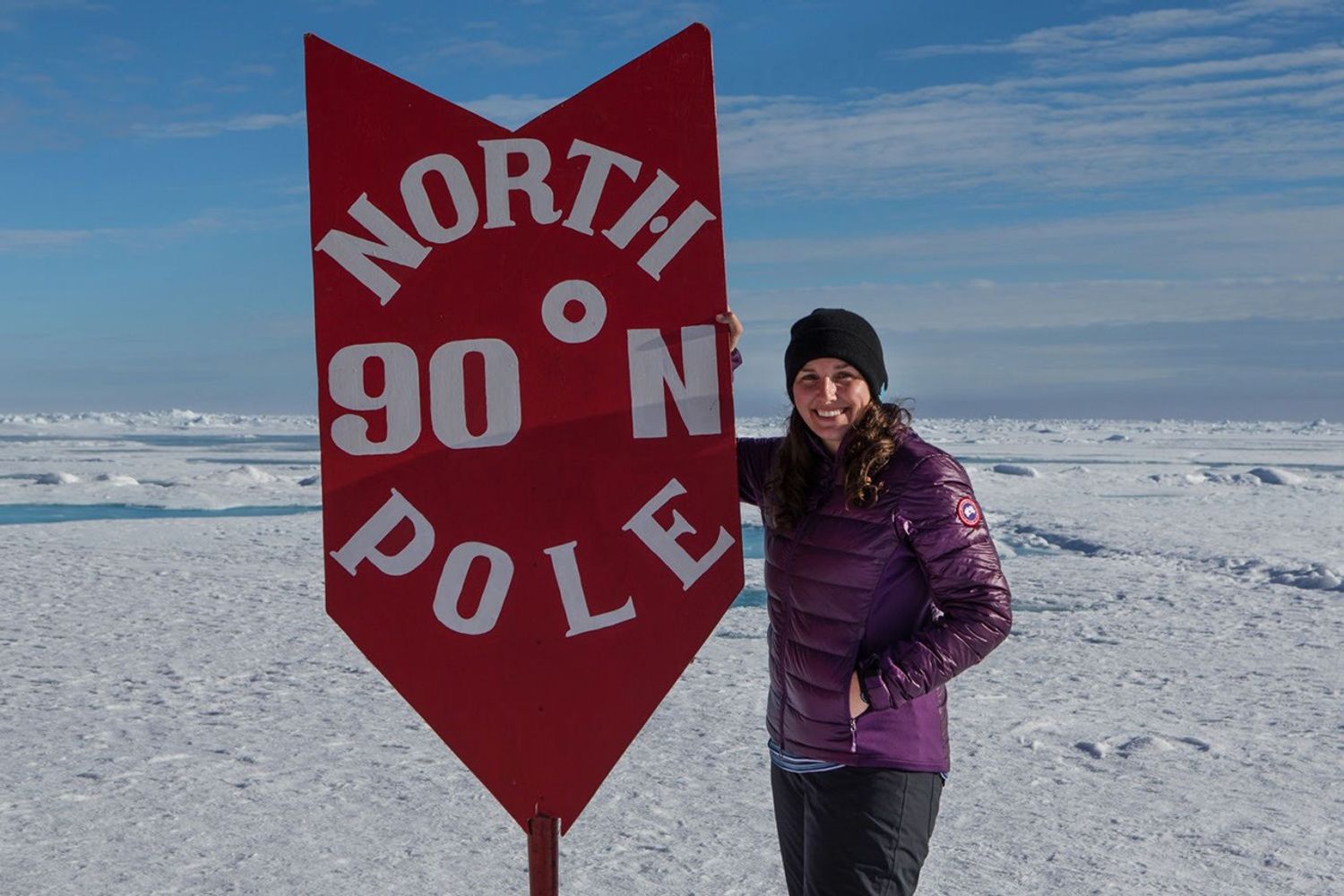

Lauren Farmer’s day job is definitely a dream job: As a polar guide in the expedition cruise industry, she introduces adventure travelers to the wildlife and icy landscapes of Antarctica and the Arctic. In her free time, though, she loves to observe clouds with NASA's free citizen science app GLOBE Observer. Read Lauren’s full Q&A.

10. Your turn

Ready to stop reading and get out there yourself? Here are all the ways you can join the citizen science movement, from exploring the surface of Mars to searching for exotic distant objects to taking stock of mosquito larvae in your hometown.