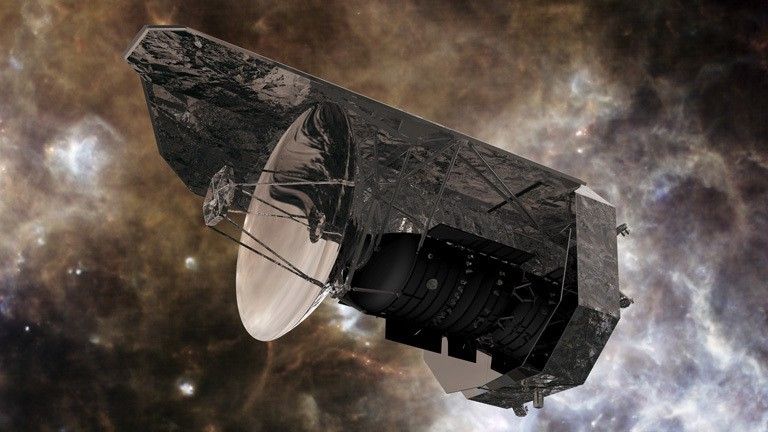

Herschel

Herschel Space Observatory

Type

Launch

Target

Objective

What Was Herschel?

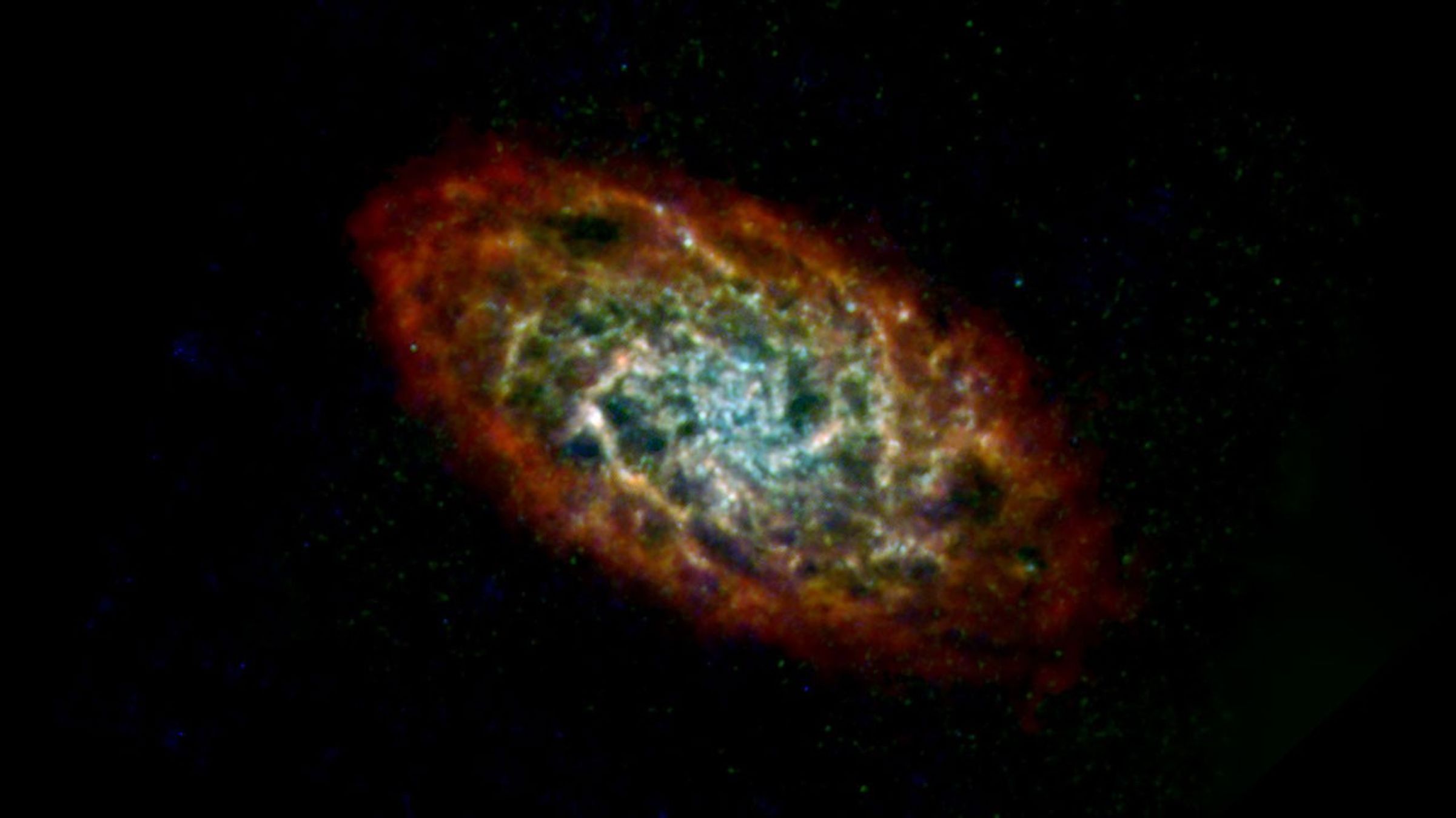

Herschel was an infrared space telescope that made important discoveries and vital contributions to almost every field of astronomy and planetary science. Herschel's main discoveries involved star formation, both in our Milky Way galaxy and in galaxies throughout cosmic history, and of key molecules – among them, water – that have made their way from interstellar clouds to burgeoning planetary systems.

| Nation | European Space Agency (ESA) |

| Objective(s) | Sun–Earth L2 Lagrange Point |

| Spacecraft | Herschel |

| Spacecraft Mass | 7,496 pounds (3,400 kilograms) |

| Mission Design and Management | ESA |

| Launch Vehicle | Ariane 5ECA (no. V188) |

| Launch Date and Time | May 14, 2009 / 13:12 UT |

| End of Mission | June 17, 2013 / 12:25 UT |

| Launch Site | Guiana Space Center, Kourou, French Guiana |

| Scientific Instruments | 1. Infrared Telescope 2. Heterodyne Instrument for the Far Infrared (HIFI) 3. Photoconductor Array Camera and Spectrometer (PACS) 4. Spectral and Photometric Imaging Receiver (SPIRE) |

In Depth: Herschel Space Observatory

Herschel was launched on the same Ariane rocket as the Planck space observatory. Both were ESA missions – with significant NASA contributions – but they had different science missions.

Herschel, at the time of launch, was the largest infrared telescope ever sent into space. It had a mirror spanning 11 feet, 6 inches (3.5 meters). It was designed to study the origin and evolution of stars and galaxies, the chemical composition of atmospheres and surfaces of solar system bodies, and molecular chemistry across the universe, to help understand the evolution of the universe.

Herschel’s mirror, one-and-a-half times bigger than the one on Hubble, was made almost entirely of silicon carbide, with 12 segments brazed together.

After launch, Ariane’s ESC-A stage sent both Herschel and Planck into a highly elliptical transfer orbit of about 168 x 744,000 miles (270 × 1,197,080 kilometers) at 6-degrees inclination to enable the spacecraft to reach the Sun-Earth L2 Lagrange Point, the local gravitationally stable point that is fixed in the Sun-Earth System, about 932,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) directly “behind” Earth as viewed from the Sun.

Herschel did not have a dedicated engine for major course changes but used its own small thrusters for minor corrections. Herschel’s operating lifetime was expected to be about three-and-a-half years, determined by the amount of coolant available for its instruments.

In mid-July 2009, about two months after launch, Herschel entered a Lissajous orbit with an approximately 497,000 miles (800,000 kilometers) radius around L2 and began active operations on July 21. (Herschel’s distance from Earth varied, depending on its orbital position, between 746,000 to 1.1 million miles (1.2 and 1.8 million kilometers).

The observatory’s operations were organized in 24-hour cycles where it communicated with ground control for three hours every day with the remainder of the time dedicated to scientific observations.

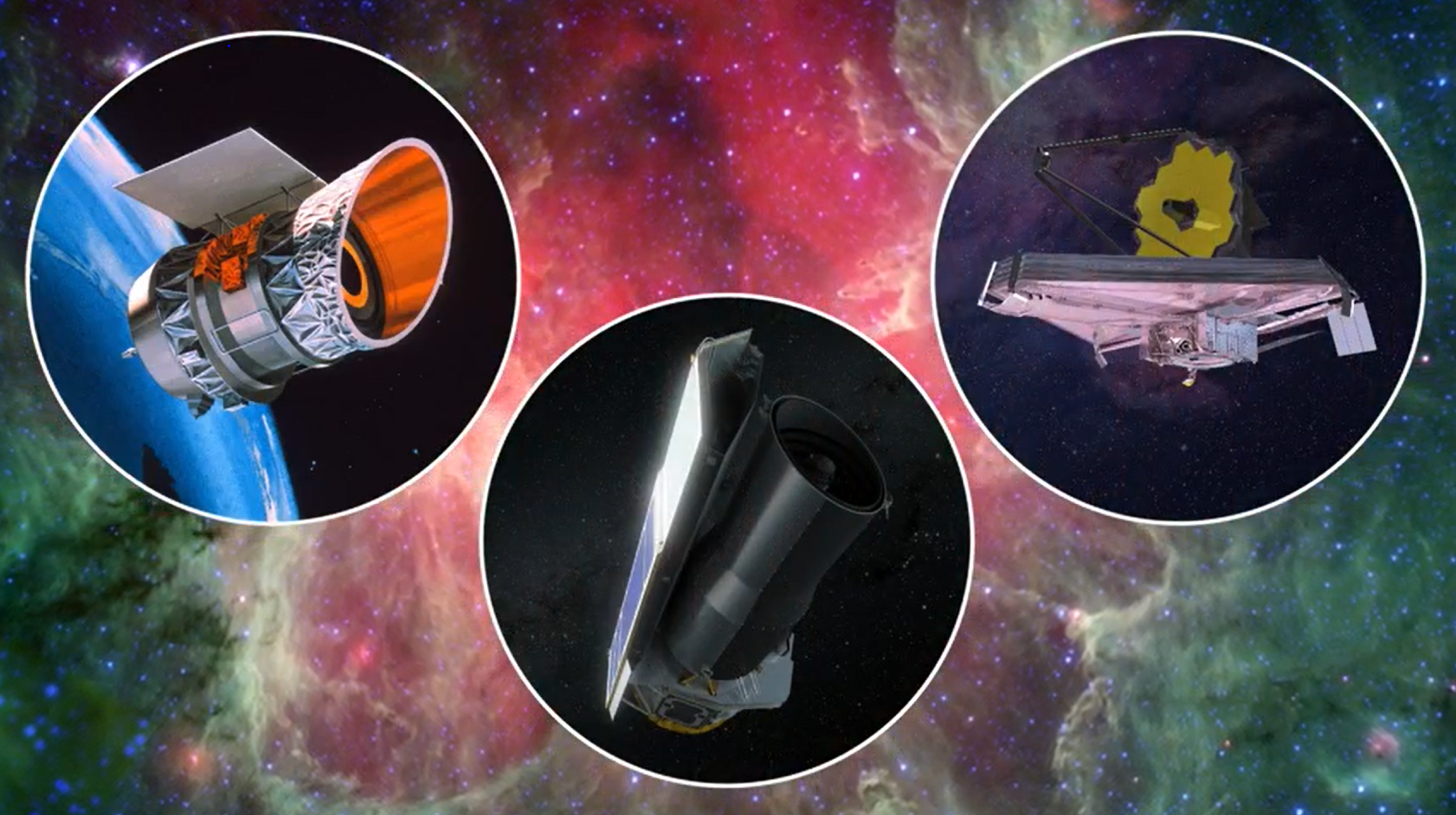

Less than a year later, at a symposium to discuss the first results of Herschel, scientists reported a number of major findings: Herschel had found high-mass protostars around two ionized regions in the Milky Way, showing an early phase in the evolution of stars; the HIFI instrument (which had actually been inoperable due to a glitch between August 2009 and February 2010) had investigated the trail of water in the universe over a wide range of scales, from the solar system to extragalactic sources; and Herschel found a previously unresolved population of galaxies in the GOODS (Great Observatories Origins Deep Survey) fields identified by the Hubble, Spitzer, and Chandra spacecraft.

In August 2011, Herschel mission scientists reported that they had identified molecular oxygen in the Orion molecular cloud complex, previously reported by the Swedish Odin satellite. Herschel data also suggested that much of Earth’s water could have come from comets, results suggested by observations of Comet Hartley 2 -- although this idea has been dispelled since. Observations by Herschel, in fact, confirmed that Comet Shoemaker-Levy’s impact into Jupiter in 1994 had actually delivered water to the gas giant.

One of the oldest objects in the universe was located in 2013. Scientists published results in April that showed the existence of a starburst galaxy that had produced over 2,000 solar masses of stars a year, originating only 880 million years after the Big Bang.

On April 29, 2013, Herschel finally ran out of the liquid helium coolant required to maintain the operational temperature of the instrument detectors. On May 13-14, the spacecraft conducted a maneuver with its thrusters to boost it out of orbit around L2 and into its final resting place in heliocentric orbit. (A possible end on the lunar surface was also contemplated but not chosen because of cost).

Following the last maneuver to deplete the propellant on board, at 12:25 UT on June 17, 2013, the final command to terminate communications was sent to Herschel, rendering the spacecraft dead. After a highly successful mission, the inert spacecraft will remain in heliocentric orbit.

Scientists continued analyzing the vast amount of data returned from the observatory. For example, in January 2014, scientists announced that data from Herschel indicated the definitive detection of water vapor on the dwarf planet Ceres, a discovery that came before the arrival of NASA’s Dawn mission at Ceres. This research was part of the Measurements of 11 Asteroids and Comets Using Herschel (MACH-11) program.

The observatory is named after British astronomers and siblings William Herschel (1738–1822) and Caroline Herschel (1750–1848).

Source

Siddiqi, Asif A. Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration, 1958-2016. NASA History Program Office, 2018.