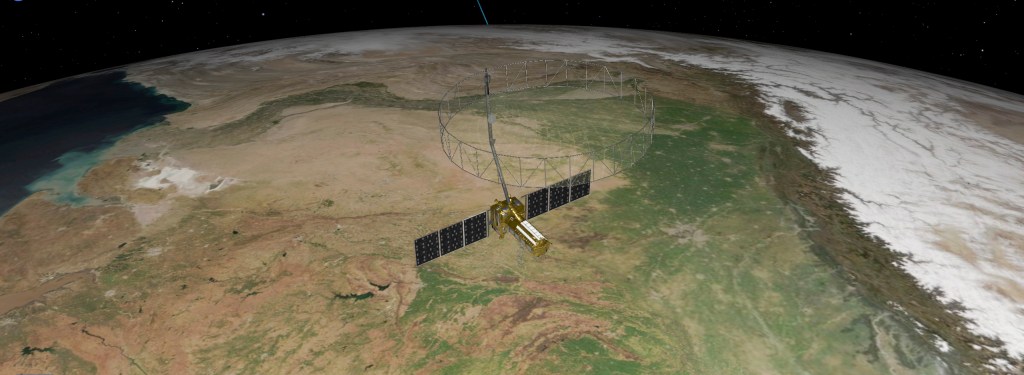

Interplanetary driving school requires a good vehicle, and few have proven as instructive and dependable as Cassini for hundreds of young engineers.

They are the Cassini cohort. Joan Stupik was in high school when Cassini arrived at Saturn. A bachelor’s and a master’s degree later, as a fresh guidance and control engineer at the Lab, she slipped into whatever non-descript chair in Building 230 passed for the driver’s seat of the nearly 20-year-old craft.

The scientists want to push the limits of the spacecraft as much as they possibly can, whereas the engineers—we’re in charge of the health of the actual hardware.- Joan Stupik, Cassini Mission Engineer

After more than three years, Stupik has absorbed valuable lessons from her time at the wheel. Some were expected but still novel, like the nearly three hours of lag between transmission of a command and receipt of an answer from the craft. When the reply did arrive, it had the fast-fading charm of a string of digits unspooling across a monitor.

Watching engineers and scientists argue—that was educational.

“One of the things that never occurred to me until I was actually working here was that there’s a very interesting relationship between the engineers who are operating the spacecraft and the scientists who are using the data,” Stupik said. “The scientists want to push the limits of the spacecraft as much as they possibly can, whereas the engineers—we’re in charge of the health of the actual hardware.”

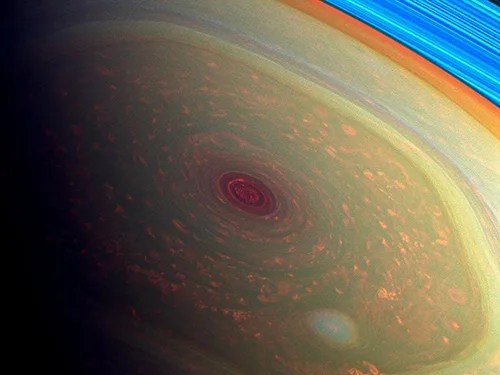

These days the scientists are winning, because when your vehicle is headed to the Saturnine scrap yard in less than six months, you may as well take a hard corner.

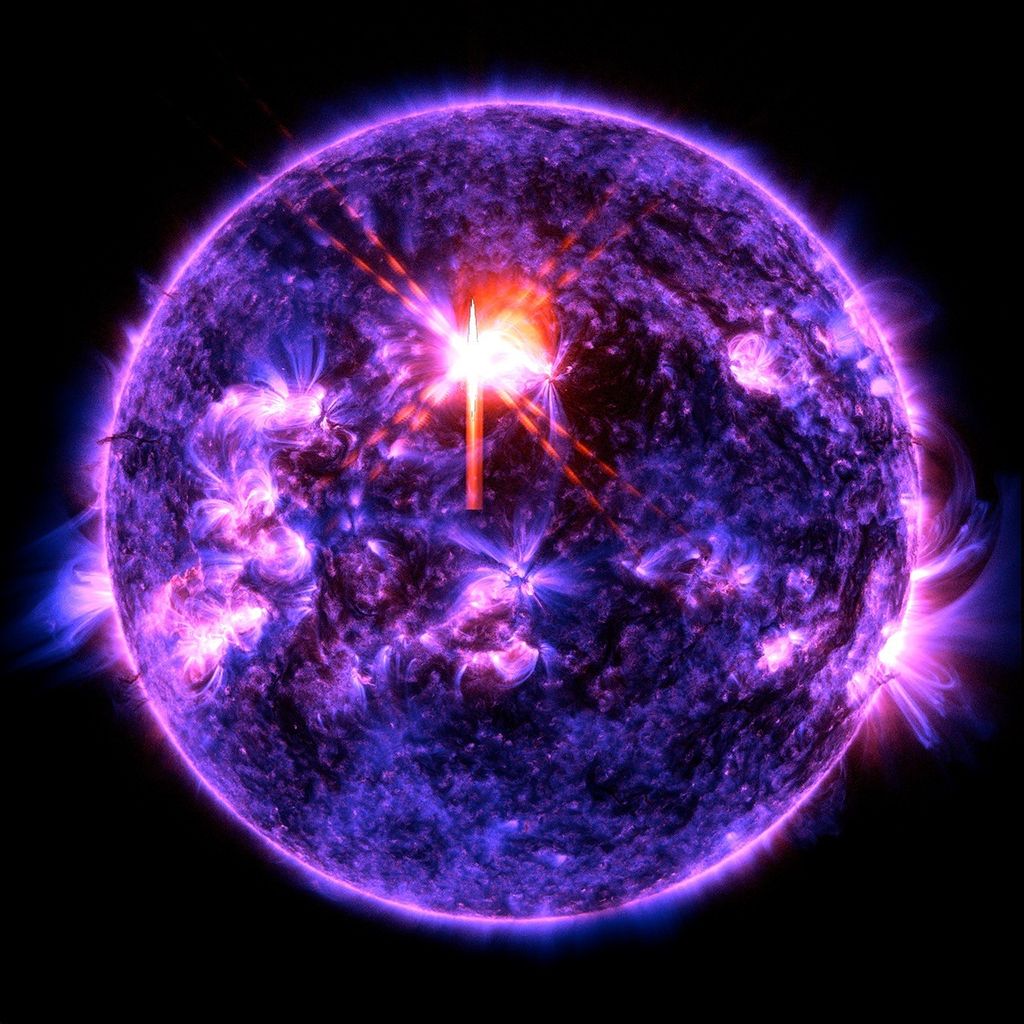

Or several. The Grand Finale consists of repeated dives to explore Saturn’s cluttered rings—maneuvers too risky to attempt when the craft was studying the planet and its moons. It was Cassini that discovered liquid water under the icy sheath of Enceladus, upending scientific consensus and raising a new candidate in the search for life.

“All of our hardware is still working really well, so we have relaxed a lot of the constraints that we used to put on the scientists, for how fast they could turn and that kind of thing. At this point everything’s going to be fine—engineering-wise,” Stupik qualified with a laugh, because for once the demise of the craft is part of the plan.

Cassini has graduated several hundred alumni at JPL alone, with thousands more around the world on teams dedicated to instruments aboard the spacecraft. The mission supported hundreds of doctoral and post-doctoral students during its flight years.

Stupik is spending only half her time on Cassini these days. With the other half, she is taking her experience to the design team for her next vehicle: the Europa Clipper.

Why Cassini Matters

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft and ESA’s Huygens probe expanded our understanding of the kinds of worlds where life might exist and eight more reasons the mission changed the course of planetary exploration.

Nine Reasons Cassini-Huygens Matters

Grand Finale Resources

A collection of graphics, documents, videos and other resources that showcase the Cassini mission's Grand Finale on Sept. 15, 2017.