7 min read

Cassini is currently orbiting Saturn with a period of 21.9 days in a plane inclined 0.4 degree from the planet's equatorial plane. The most recent spacecraft tracking and telemetry data were obtained on Sept. 16 using the 70-meter diameter Deep Space Network station in California. The spacecraft continues to be in an excellent state of health with all of its subsystems operating normally except for the instrument issues described at http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/news/significantevents/anomalies .

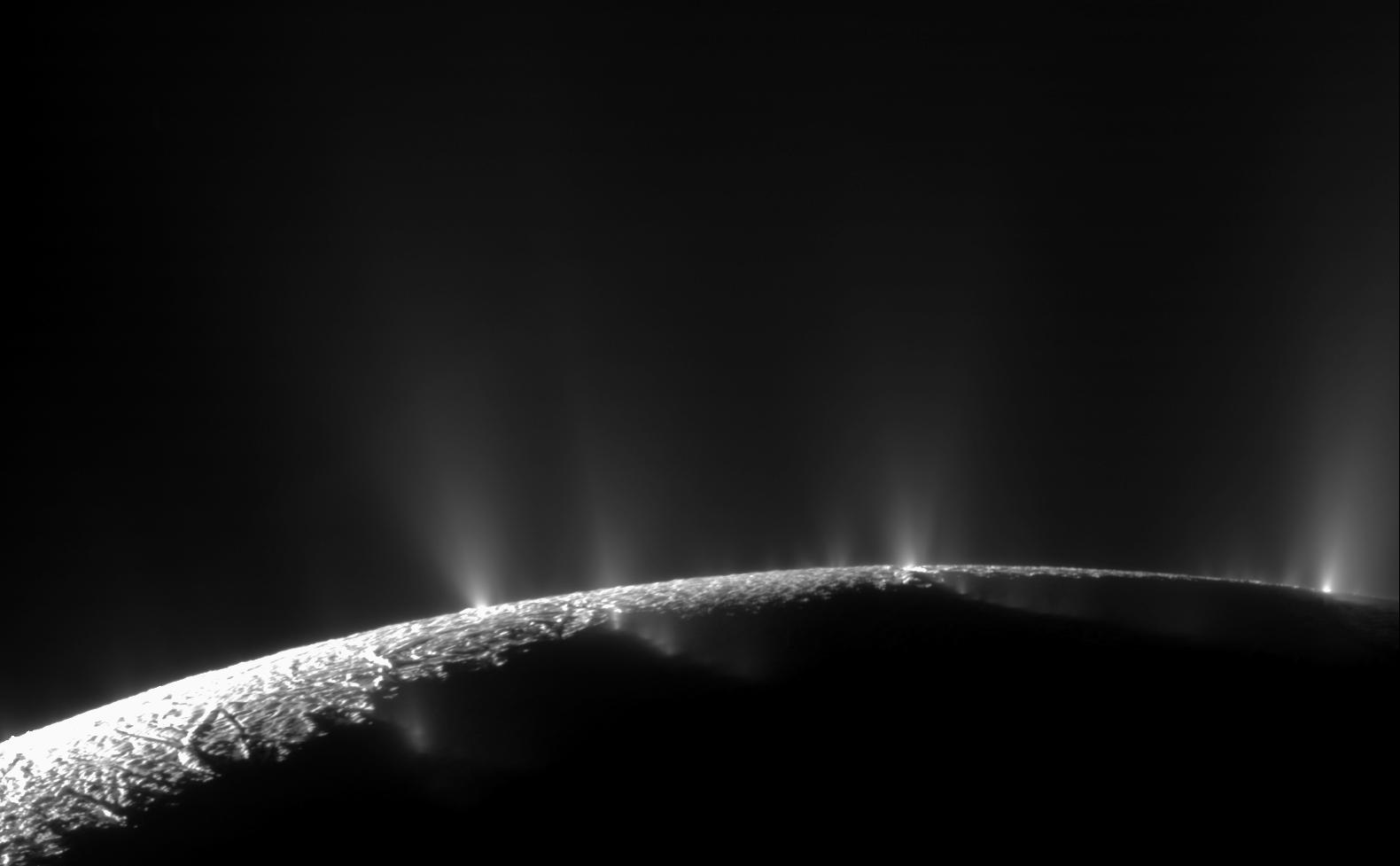

It was a surprise to learn that an object as small as Saturn's moon Enceladus, at just over 500 kilometers in diameter, would be geologically active. In 2005, though, Cassini discovered south-polar geysers. They were later found to be salty, hinting of deep hydrothermal activity. Traces of organic compounds were also measured in the plume material lending more credence to the presence of hydrothermal activity. But a global sub-surface ocean? The evidence is now solid, and Enceladus joins ranks with Jupiter's moon Europa as a water-world, with a water ice crust that floats above a layer of liquid water. The discovery is fully explored in a paper just published in Icarus; this exciting news was released on Tuesday: http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/news/newsreleases/newsrelease20150915 .

Having sped through periapsis last week, Cassini spent this week "falling up" toward a Sept. 19 apoapsis. While commands from the on-board S90 sequence controlled its activities, sequence implementation teams continued preparing the 10-week command sequences S92 and S93. Work on the S91 sequence was wrapped up on Friday with formal approval to send it to the spacecraft, so it can begin operating on Sept. 21. With the mission ending within two years from now, the flight team's planning activities are converging toward an exciting and scientifically unique Grand Finale.

Wednesday, Sept. 9 (DOY 252)

The flight team used the large DSN station in Australia early today to uplink the last of the "Instrument-Expanded Block" commands that will support the S91 sequence, which will begin executing next week. After a round trip of 170 minutes, telemetry confirmed that each of the 6,728 individual commands had been properly received.

Cassini's Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS) directed spacecraft pointing to examine Saturn's moon Dione for five hours. While CIRS mapped the thermally anomalous terrain on Dione's night side, the Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS) and the Visible and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) also acquired data while "riding along." Dione was around 425,000 km from Cassini's telescopes.

With the Dione observations finished up, Cassini turned to point the ISS's cameras to the small moon that made history this week. Enceladus was nearly twice as far away as Dione was, but ISS observed its plumes while they were brightly backlit by the Sun (raw images are always available here: http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/photos/raw ). VIMS and the Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph (UVIS) rode along. This 2.5-hour observation was repeated on the following day, at a distance of about one million km, and then again for 8.25 hours on Friday from about the same distance. These observations help characterize the variability in the plumes' activity.

Named after a giantess in Norse mythology, Saturn's irregular moon Greip is no giant at about six km in diameter. It has an unusual orbit that goes around the planet backwards, retrograde, while remaining in the equatorial plane. Its highly elliptical orbit takes it between 12.7 and 24.3 million km from Saturn. Today, Cassini's ISS began its only observation of this very small body. Lasting nearly 20 hours, it should reveal information about Greip including its rotation rate.

Thursday, Sept. 10 (DOY 253)

Some members of the Cassini Science team who were invited guests at the science-fiction convention DragonCon in Atlanta, Georgia, a week ago, reported having shared some cutting-edge, non-fiction, planetary science. Topics included Saturn, Europa, Pluto, Mars and more. More than 2,200 audience members attended presentations made by speakers from JPL.

Friday, Sept. 11 (DOY 254)

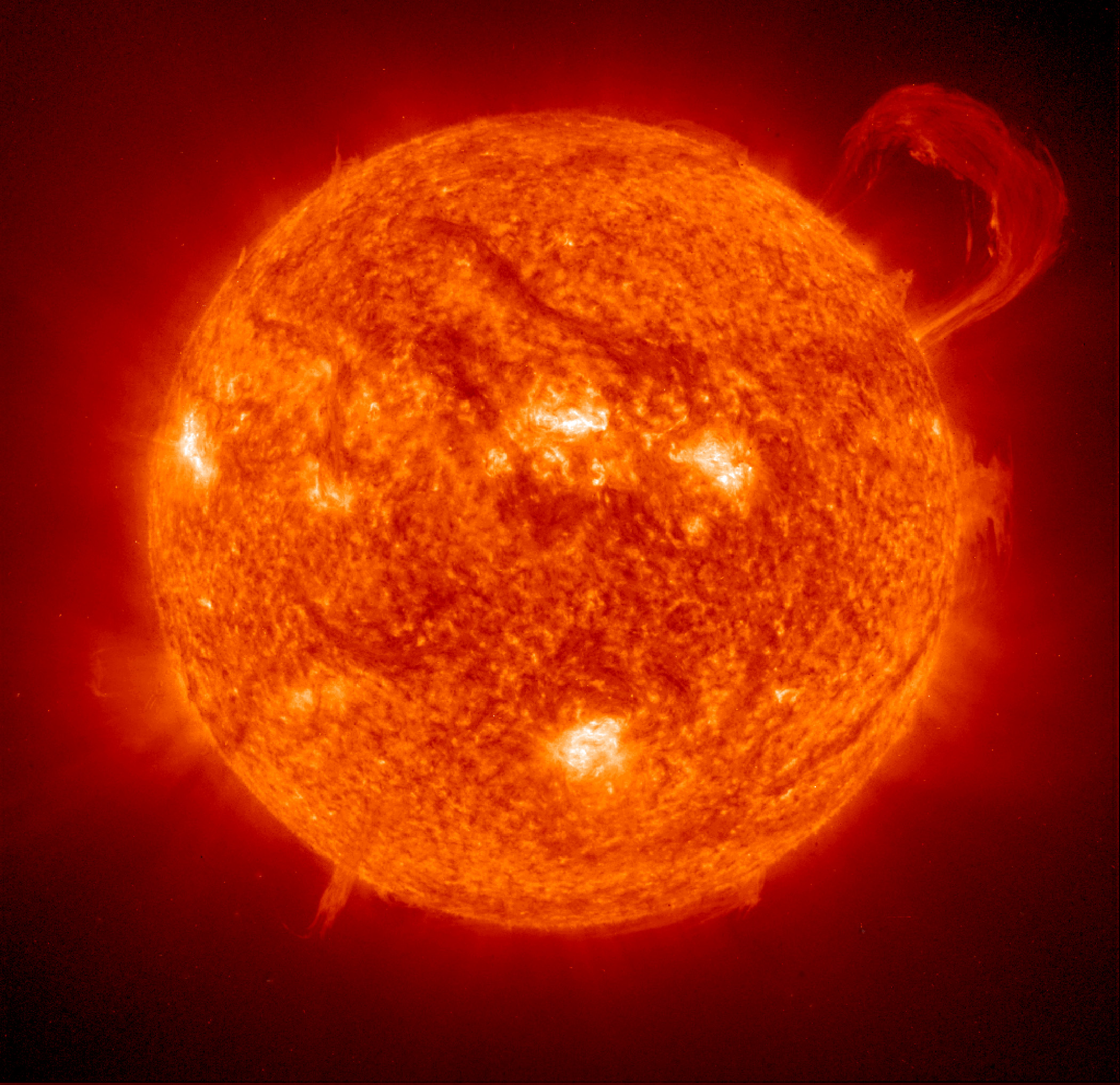

After today's Enceladus observation completed, UVIS took the reins for 15 hours to watch Saturn's auroral oval. All the other Optical Remote-Sensing (ORS) instruments participated as riders: ISS, CIRS and VIMS. "Taking the reins" means commands for UVIS, stored in the S90 sequence, initiated requests to the Attitude and Articulation Control Subsystem (AACS) to point the spacecraft. AACS then used its own stored vectors, and operated Cassini's three reaction wheels to orient the spacecraft in precisely the right directions.

Saturday, Sept. 12 (DOY 255)

It's hard to overstate how impressive a first look at Saturn is, in almost any telescope, especially when the rings are as wide open to us as they are this year. Saturn is the brightest object early these evenings in roughly the same position the Sun appeared at about 2 or 3 PM during the day, relative to any point on the horizon.

Sunday, Sept. 13 (DOY 256)

ISS started rotating the spacecraft slowly for 37 hours in such a way that its narrow-angle camera could track Saturn's irregular moon Bergelmir. The namesake of this Greip-size "irregular" was also a giant in Norse mythology; it reaches 22 million km from Saturn in its inclined retrograde orbit.

Monday, Sept. 14 (DOY 257)

To be able to carry out requests from the various instruments accurately, AACS needs to "know" precisely which way the spacecraft is facing. In addition to the nine telescopes that are part of Cassini's ORS science instruments, there are two more: one small refractor serves each of Cassini's Stellar Reference Units (SRU). These intelligent engineering devices are fixed in place with their views set 90 degrees from the views of the ORS instruments. They're always watching deep space and recognizing stars, and providing AACS the attitude reference information it needs. Today, the SRUs carried out a calibration exercise, which is typically done every nine months or so (though not always noted in these pages). The activity was accomplished while Cassini was carrying out a routine nine-hour communications and tracking session with the Deep Space Network; the SRUs' telescopes were carefully aimed away from bright sources like Saturn during the five-hour calibration.

A majestic view of Saturn's night side, ten times the diameter of Earth, is the featured image today. The enigmatic hexagon on Saturn's sunlit north pole, and some cloud bands deep below the haze are clearly seen on the huge crescent. The rings are dark only because of ISS's "infrared sunglasses" -- a special infrared filter that ISS had rotated into its optical path, rejecting much of the rings' reflected sunlight:

/resources/16242 .

Tuesday, Sept. 15 (DOY 258)

Today marks two years until the end of Cassini's incredible mission. One final distant flyby of Titan on Sept. 11 of 2017 will lower Cassini’s Saturn flyby altitude to the point where atmospheric capture is inevitable. Four days later, Cassini will enter Saturn’s atmosphere. Loss of communication, which will occur when the giant planet's atmosphere overcomes AACS's ability to control the spacecraft, is predicted to be within about an hour of 5:30 AM Pacific time (Earth-receive time). Disposing the spacecraft into Saturn will prevent any contamination of possibly habitable moons like Titan and Enceladus.

Cassini turned to an attitude favoring the Magnetospheric and Plasma Science (MAPS) instruments. The attitude was also convenient for CIRS, which then proceeded to map Saturn at mid-infrared wavelengths, measuring temperatures in the upper troposphere and at the tropopause.

ISS conducted three Saturn storm-watch observations this week: two on Friday and one on Saturday. VIMS rode along with Saturday's and one of Friday's; all were two-minute observations.

During the past week, the Deep Space Network communicated with and tracked Cassini on five occasions, using DSN stations in California and Australia. A total of 6,734 individual commands were uplinked, and about 781 megabytes of telemetry data were downlinked and captured at rates as high as 124,426 bits per second.

This illustration shows Cassini's position on Sept. 15: http://go.nasa.gov/1flNDtq . The format shows Cassini's path over most of its current orbit up to today; looking down from the north, all depicted objects revolve counter-clockwise, including Saturn along its orange-colored orbit of the Sun.