7 min read

Cassini is currently orbiting Saturn with a period of 12.7 days in a plane inclined 1.3 degrees from the planet's equatorial plane. The most recent spacecraft tracking and telemetry data were obtained on Nov. 18 using the newest of the Deep Space Network's stations, a 34-meter diameter antenna in Australia. The spacecraft continues to be in an excellent state of health with all of its subsystems operating normally except for the instrument issues described at http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/news/significantevents/anomalies .

Early on Wednesday, Cassini sped through periapsis, the closest point in its orbit around Saturn. Later that day it took advantage of a non-targeted encounter with Saturn's moon Tethys at a distance of 8,900 kilometers. Then on Thursday, Cassini carried out its targeted encounter T-114 with Saturn's planet-like moon Titan. By Tuesday, the spacecraft had coasted all the way "up" to apoapsis.

Cassini's Navigation team used the T-114 flyby for gravity assist, reducing Cassini's orbit period from 13.9 to 12.7 days. It also ratcheted up the inclination of Cassini's orbit slightly, from 0.6 to 1.3 degree measured from Saturn's equatorial ring plane. This small increase portends more to come. All future targeted Titan encounters will have their effect on Cassini's orbital inclination, until April 2017, when the inclination will be over 62 degrees. At that time, the final Titan encounter T-126 will modify Cassini's orbit so its next 22 periapses will occur in between the rings and Saturn's atmosphere.

Wednesday, Nov. 11 (DOY 315)

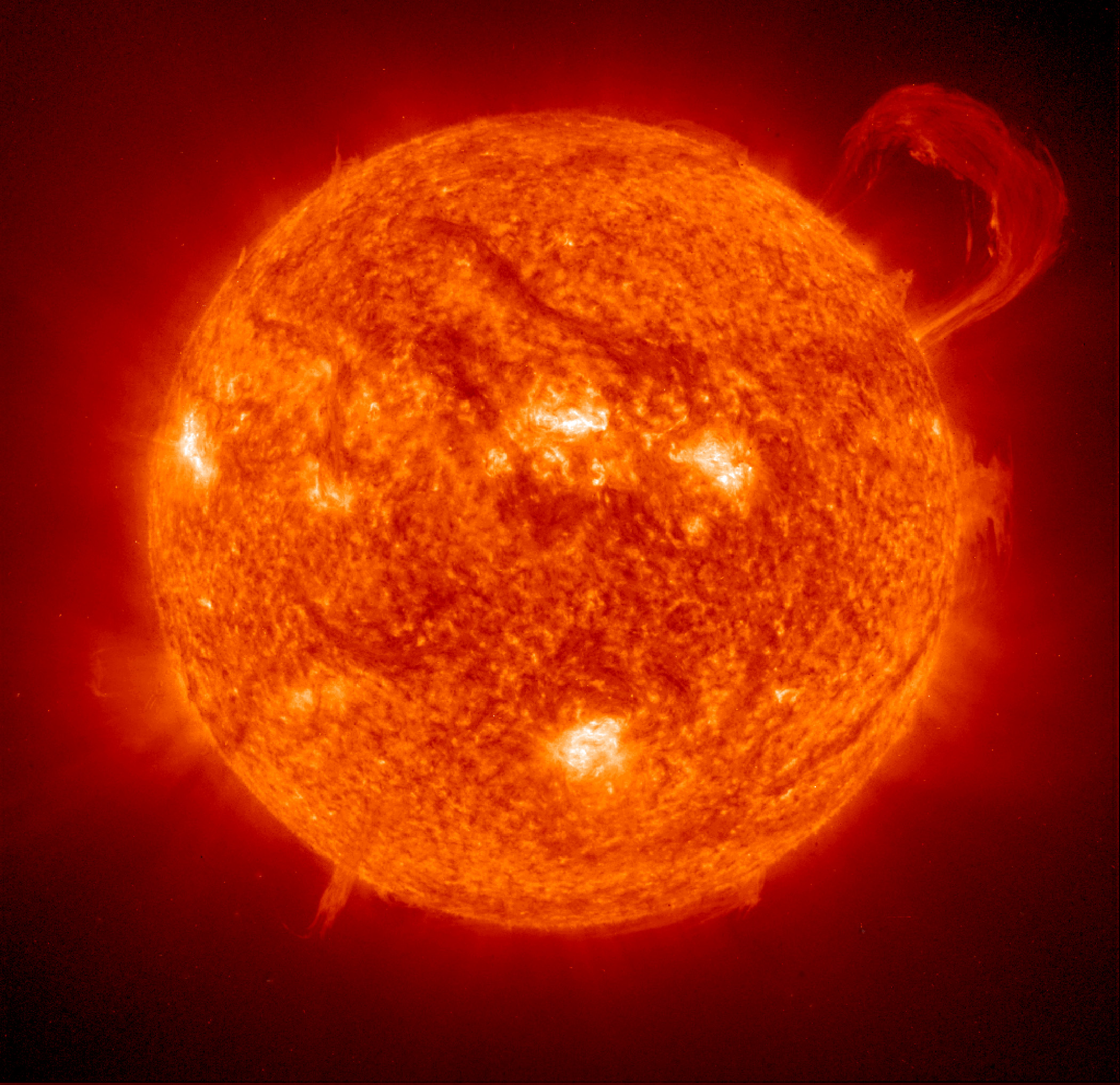

While speeding inward towards periapsis, Cassini's Cosmic Dust Analyzer (CDA) spent 2.5 hours studying in particular the relatively large grains of dust in that region. The Visible and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) then took over control of spacecraft pointing to observe the red star named 30 Piscium for nearly three hours while it was occulted by Saturn's rings. During this observation, Cassini passed periapsis, having come within 114,500 km of Saturn's visible edge. Its speed at that point was 72,026 km per hour relative to the planet.

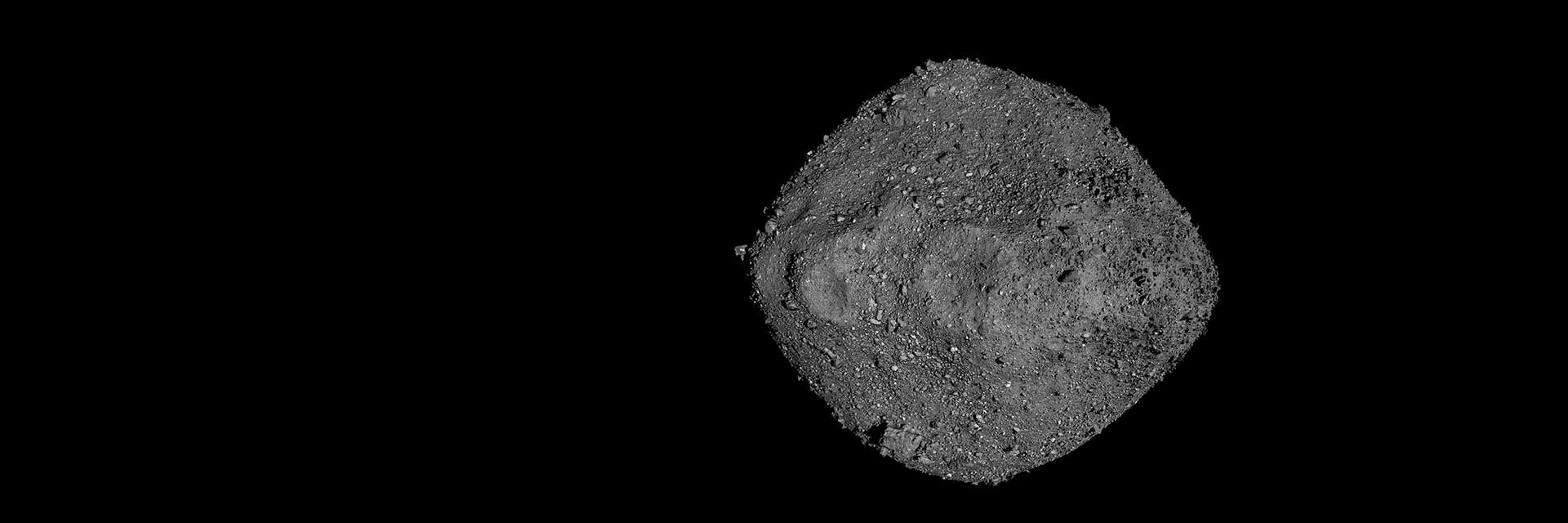

As soon as the VIMS stellar ring occultation experiment was completed, CDA took back control in order to sample the faint trail of dust that shares the orbit of Saturn's moon Pallene. Meteors impacting Pallene, which is around six km in diameter, dislodge the dust that forms the faint Pallene ring. This annotated image from 2006 identifies that fine ring: /resources/13313 .

Immediately following CDA's experiment, Cassini turned to point the optical remote-sensing instruments -- the telescopes -- to examine Saturn's moon Tethys, which is around 1,000 km in diameter. For 1.75 hours while the non-targeted encounter played out, the Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS), the Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS), the Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph (UVIS), and VIMS, made observations of the satellites' icy surface. They captured views and measurements of some very curious reddish-color streaks that Cassini discovered earlier on Tethys's surface. "Non-targeted" means that no propulsive maneuvers were devoted to achieving the encounter.

Finally, CDA resumed control for 4.25 hours to continue measuring the relatively large dust grains near periapsis.

High above Titan's south pole, an enormous cloud feature lingers, and Cassini has been watching it. Today's news feature highlights and discusses the prominent phenomenon: http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/news/cassinifeatures/feature20151111 .

Thursday, Nov. 12 (DOY 316)

CIRS and VIMS spent nearly 21 hours taking turns controlling the spacecraft pointing today, to study the atmosphere of Saturn's largest moon. ISS rode along, taking advantage of the pointing, and taking images. The infrared instruments were measuring the temperature and composition of the strange south-pole cloud mentioned above, as it continues to develop in the advancing southern autumn.

Only 35 years ago today, the Voyager-1 Spacecraft made its closest approach to Saturn on a fast but extremely productive flyby of the system. It also succeeded in conducting solar-occultation and radio-occultation experiments with Titan; had these experiments failed, Voyager 2 would have been re-targeted to attempt them, foregoing its ability to encounter Uranus and Neptune. The successful Voyager-1 encounter provided groundbreaking measurements of the huge moon's mass, and probed its atmosphere with the occultations. The dynamics of the encounter then flung the spacecraft on a northerly course, eventually into interstellar space. Both Voyagers continue to communicate with their flight team basically every day via the Deep Space Network; round-trip light-time to Voyager 1 today is 37 hours 8 minutes.

Friday, Nov. 13 (DOY 317)

The day after the anniversary of Voyager-1's historic encounter, Cassini, whose instruments were designed with better capabilities for observing Titan, encountered that body today. Now, of course, Titan is known to have rivers and lakes on its surface, as well as a complex atmosphere. The T-114 encounter page has the details, including an animation, of today's event: http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/flybys/titan20151113 .

Saturday, Nov. 14 (DOY 318)

Cassini's Radar instrument kept the spacecraft's high-gain antenna trained on Titan for two hours today, collecting data via its passive radiometer mode, both for science investigation and instrument calibration.

Sunday, Nov. 15 (DOY 319)

ISS took two minutes to make a storm-watch observation on Saturn, and then viewed Enceladus for 90 minutes to take images for optical navigation purposes. Next, CIRS observed Saturn’s atmosphere for twelve hours, collecting spectral data to better determine the atmosphere's composition. ISS and VIMS rode along with CIRS. Following this, ISS made another two-minute Saturn storm-watch observation. The spacecraft then turned to communicate with Earth.

Based on the latest iterations of the Navigation team's solutions, the flight team created and sent up commands to perform Orbit Trim Maneuver (OTM)-431. This maneuver turned the spacecraft and fired its hydrazine-fed rocket thrusters for 105 seconds. This provided a change in velocity of 103 millimeters per second needed to clean up Cassini's trajectory following the T-114 encounter.

Monday, Nov. 16 (DOY 320)

CDA took the reins for 15 hours today to sample dust that orbits Saturn in the retrograde direction.

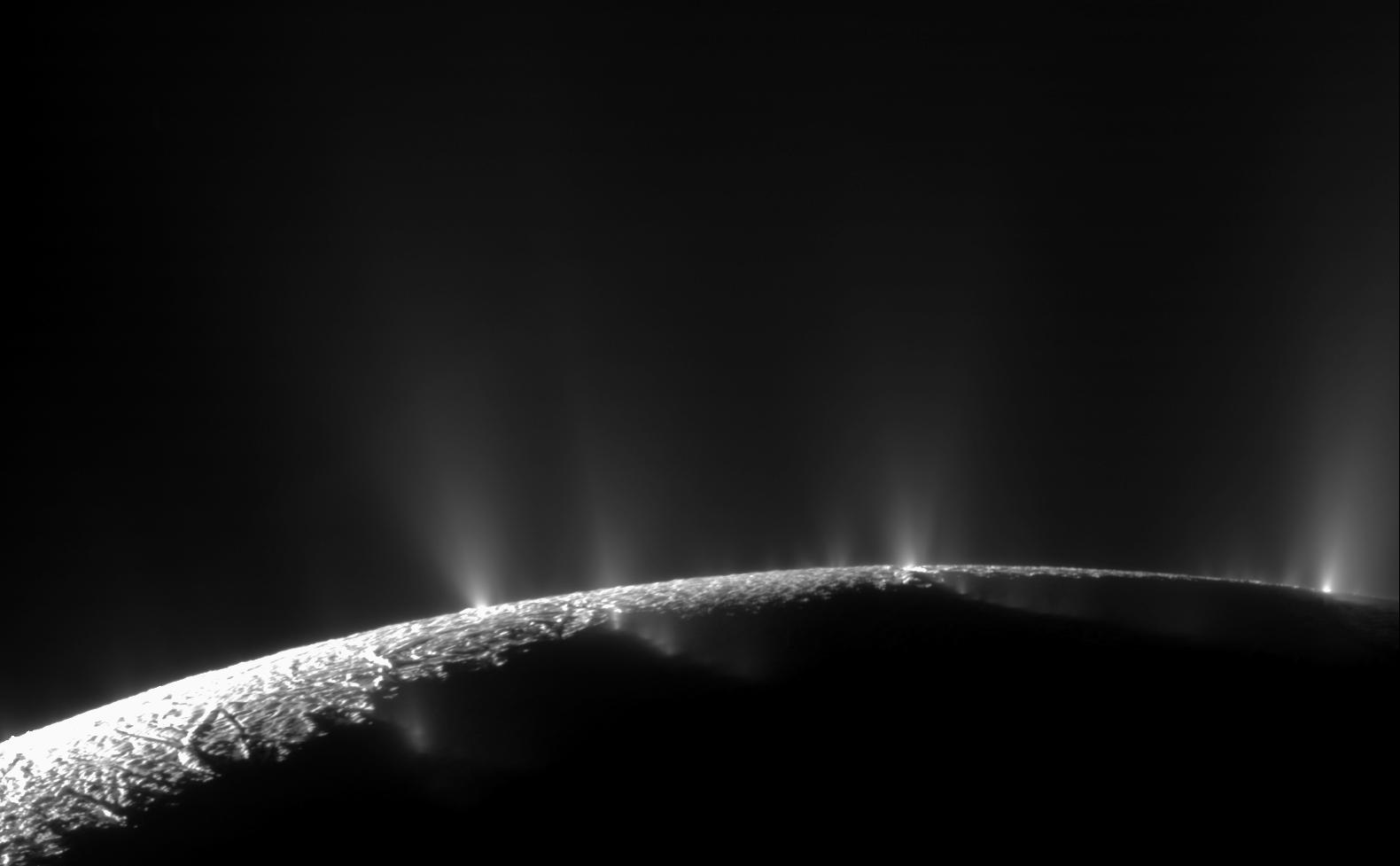

Even 35 years ago, Saturn's little icy moon Enceladus was known to be the most reflective body in our solar system, but the puzzle as to why remained to be resolved by Cassini. In an image featured today, Enceladus's high albedo is clear to see: /resources/16272 .

Tuesday, Nov. 17 (DOY 321)

ISS, CIRS and VIMS performed a 90-minute observation in the Titan monitoring campaign, from a distance of 1.9 million km. Next came another two-minute Saturn storm watch by ISS, and then ISS, CIRS and VIMS jointly made an 18-hour observation of Saturn's E ring, seen edge-on. The E ring is formed by the plume of material issuing from Enceladus's south-pole geysers.

While the E-ring observation was taking place, Cassini coasted through apoapsis, the high point in its orbit of Saturn. This marked the start of Orbit #226. The spacecraft had slowed to 6,059 km per hour relative to Saturn, and reached an altitude of 1.95 million km from the planet.

During the week, the Deep Space Network communicated with and tracked Cassini on five occasions, using stations in Australia. A total of 13,216 individual commands were uplinked, including commands that will support Cassini's instruments when the next ten-week command sequence S92 takes effect. About 1,331 megabytes of telemetry data were downlinked and captured at rates as high as 110,601 bits per second.

This illustration shows Cassini's position on Nov. 17: http://go.nasa.gov/1jOsKKv . The format shows Cassini's path over most of its current orbit up to today; looking down from the north, all depicted objects (except the background stars of course) revolve counter-clockwise, including Saturn along its orange-colored orbit of the Sun.