4 min read

From peering into hurricanes to tracking El Niño-related floods and droughts to aiding in disaster responses, the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission has had a busy decade in orbit. As the GPM mission team at NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) commemorates its Feb. 27, 2014 launch, here are 10 highlights from the one of the world's most advanced precipitation satellites.

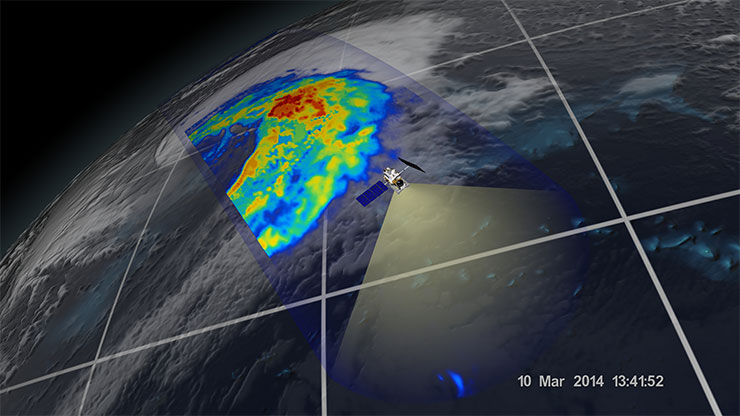

Less than a month after launch, NASA and JAXA released the first images captured by the GPM Core Observatory. It measured precipitation falling inside a March 10, 2014, cyclone over the northwest Pacific Ocean, approximately 1,000 miles east of Japan.

Combining data from a constellation of satellites that together observe every part of the world roughly every three hours, the GPM team mapped how rain and snow storms move around the planet. As scientists have worked to understand all the elements of Earth’s climate and weather systems – and how they could change in the future – GPM has provided comprehensive and consistent measurements of precipitation.

The GPM Core Observatory flew over Hurricane Arthur five times between July 1 to 5, 2014 – the first time a precipitation-measuring satellite was able to follow a hurricane through its full life cycle with high-resolution measurements. In the July 3 image, Arthur was just off the coast of South Carolina. GPM data showed that the hurricane was asymmetrical, with spiral arms (rain bands) on the eastern side of the storm but not on the western side.

In 2017, NASA used assets and expertise from across the agency to help respond to Hurricane Harvey in southern Texas. The agency’s GPM mission team produced rainfall accumulation graphics and unique views of the structure of Harvey during various phases of development and landfall.

Predicting floods is notoriously tricky, as the events depend on a complex mixture of rainfall, soil moisture, the recent history of precipitation, and much more. Snowmelt and storm surges can also contribute to unexpected flooding. With funding from NASA, researchers developed a tool that maps flood conditions across the globe.

A NASA-based team built a new tool to examine the risk of landslides. They developed a machine learning model that combines data on ground slope, soil moisture, snow, geological conditions, distance to faults, and the latest near real-time precipitation data from NASA’s IMERG product (part of the GPM mission). The model has been trained on a database of historical landslides and the conditions surrounding them, allowing it to recognize patterns that indicate a landslide is likely.

For the first time, scientists collected three-dimensional snapshots from space of raindrops and snowflakes around the world. With this detailed global dataset, scientists started to improve rainfall estimates from satellite data and in numerical weather forecast models. This is particularly helpful for understanding and preparing for extreme weather events.

The GPM team amassed and analyzed data to show the various changes in precipitation across the United States due to the natural weather phenomenon known as El Niño.

University researchers turned to data from NASA’s fleet of Earth-observing satellites to track environmental events that typically precede a malaria outbreak. With NASA funding and a partnership with the Peruvian government, they worked to develop a system to help forecast potential malaria outbreaks down to the neighborhood level and months in advance. This gave authorities a tool to help prevent outbreaks from happening.

NASA’s Precipitation Measurement Missions (PMM) – including GPM and the Tropical Rainfall Measurement Mission – have together collected rain and snowfall from space for more than 20 years. Since 2019, scientists have been able to access PMM’s multi-satellite record as one dataset.