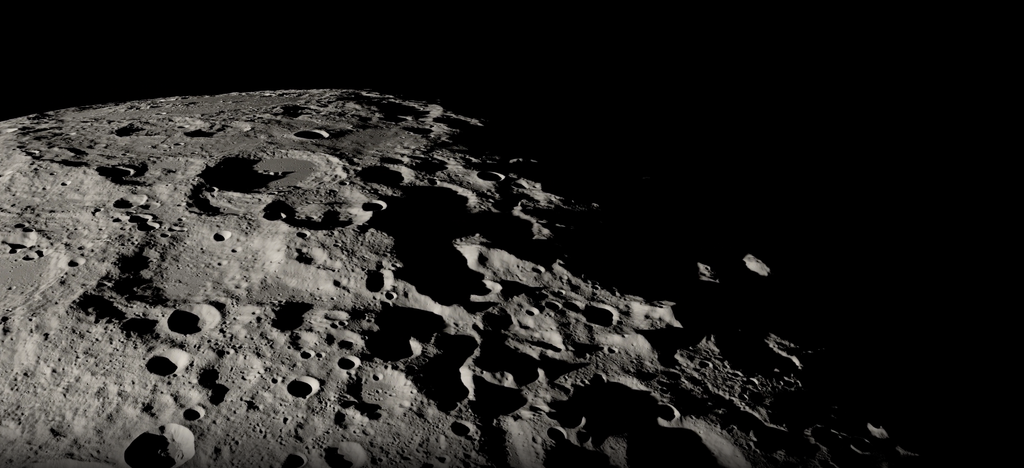

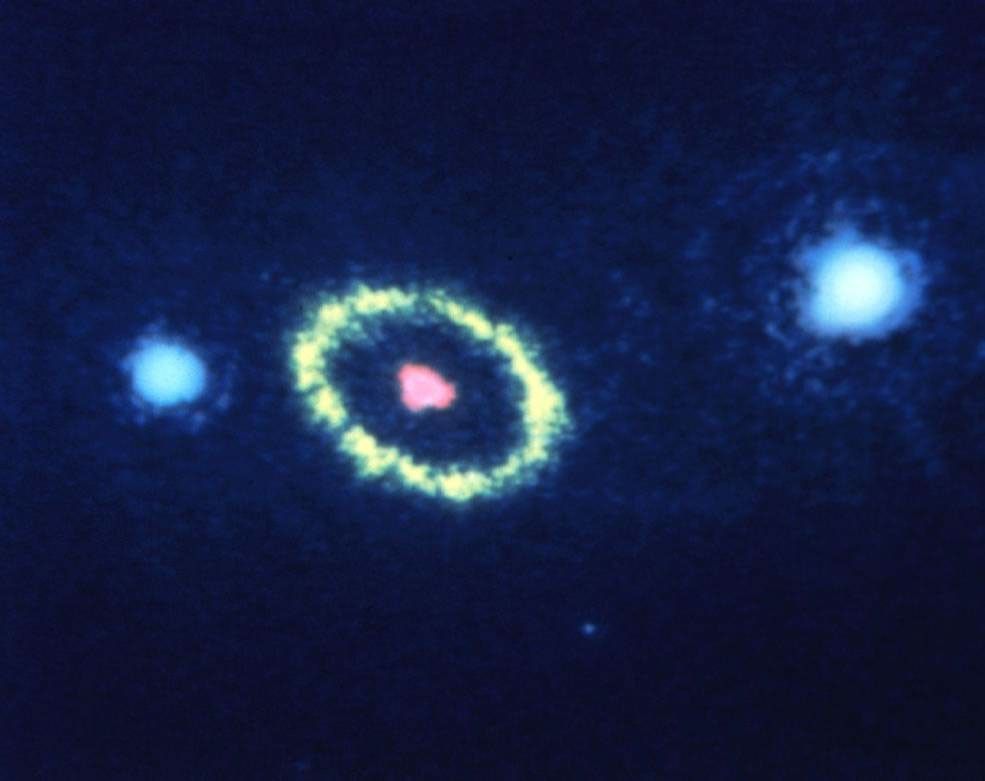

On May 20, 1990, you could hear a pin drop as a room full of scientists waited breathlessly for the initial images from the first major optical telescope in space. As a few bright points of light set against the black canvas of deep space materialized, instead of awe, the room filled with dread. Although better than any ground-based telescope could manage, the image was far less clear than anyone had anticipated.

It was possible that the Hubble Space Telescope was out of focus. This theory, however, proved incorrect. After the requisite adjustments were made, a fateful image of galaxy M100 returned looking as if it was forgotten in the pocket of a pair of jeans and thrown in the wash — mottled, blurred and hazy. It was at this moment that the Hubble team knew their telescope was in trouble.

Scientists and engineers at NASA and its partner institutions spent the next three years orchestrating a solution. Twenty-five years ago, a group of astronauts ascended in the space shuttle to accomplish a feat of unprecedented proportions: to fix Hubble, in space, while orbiting Earth at over 17,500 miles per hour. These seven astronauts would be implementing a repair and upgrade hundreds of scientists and engineers conceived, designed and tested on Earth at multiple locations including NASA’s Johnson Space Center, Goddard Space Flight Center and Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The Hubble we know and love today is the most productive space telescope ever launched. The data it has provided the world has prompted unparalleled discoveries, and it continues, after 28 years of science, to tell us more about our universe every day. Much of this incredible track record can be attributed to Hubble’s remarkable longevity. So, how has Hubble survived for so long, over a decade longer than originally intended?

The answer to Hubble’s persistent history of excellence and science lies with a wide and diverse group of dedicated individuals committed to making a telescope designed with the capability to be upgraded and repaired — also known as “servicing” — once it was already in space.

Designing for the Long Haul

“The reason I came to NASA was really to be innovative,” said Frank Cepollina, former Associate Director for the Satellite Servicing Capabilities Project and a man famed for championing satellite servicing as a concept, then seeing it through to fruition. “We were in a first-time business — the first time this stuff had ever been done, so there was a lot of learning and testing and creating.”

Cepollina, affectionately known by his colleagues as “Cepi,” helped conceptualize the first plans to fix an orbiting spacecraft in person on a mission called SolarMax, which astronauts successfully repaired in 1984. He earned the nickname “Father of Satellite Servicing” as a result of his efforts. This work informed the design for Hubble, a telescope built from the outset with the intention of astronauts repeatedly visiting to repair and upgrade over time in a series of servicing missions.

“We wanted to design something that could continue to work mission after mission that wouldn’t have to be redesigned and updated for each flight,” Cepi said of developing a space telescope that could be serviced numerous times. “It needed to work with the brand-new transportation vehicle we were developing: the space shuttle orbiter. So that’s really how we started innovating for Hubble.”

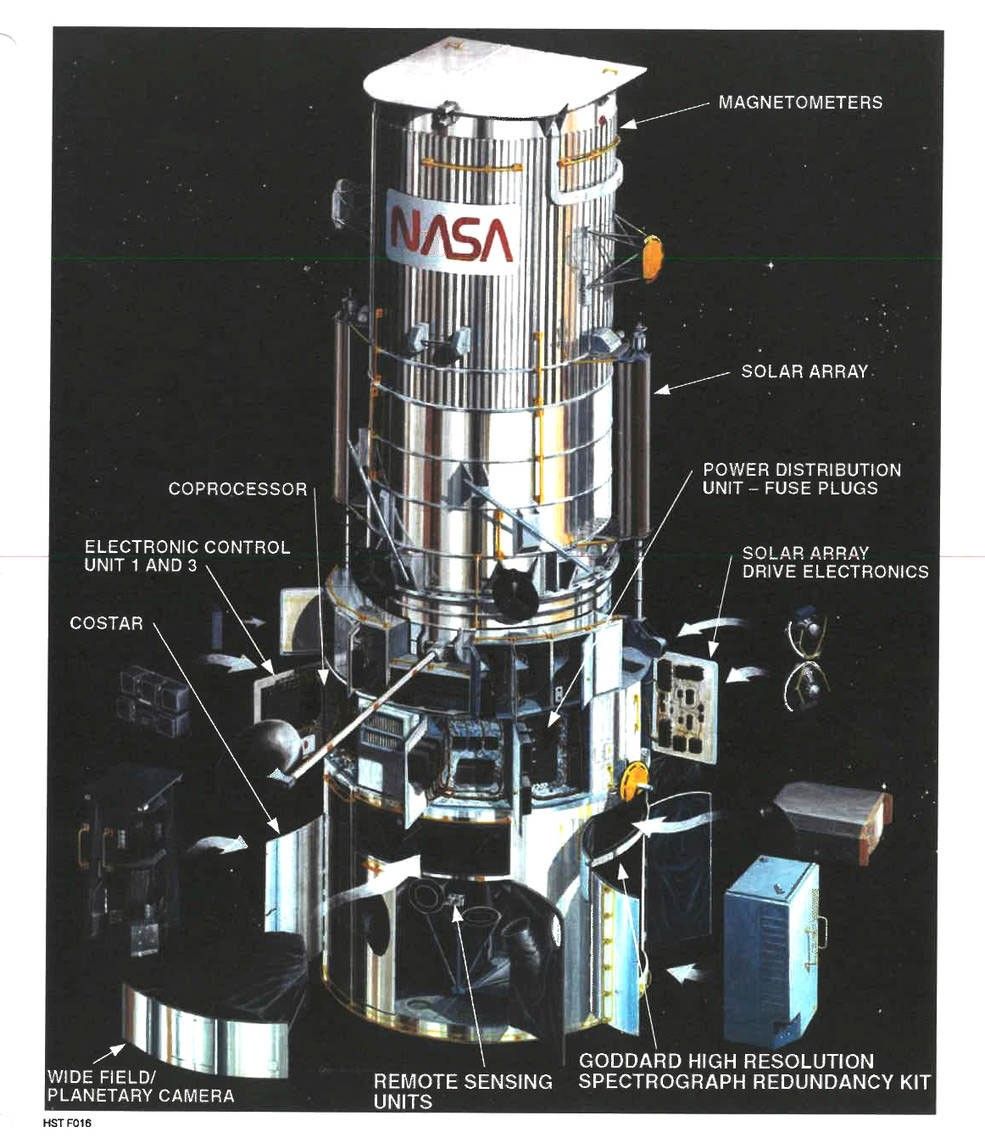

Cepi and his team focused on constructing interchangeable, modular elements for the telescope, which would allow astronauts to smoothly and efficiently swap out pieces of hardware as technology improved through the years. Each instrument would be self-contained, with its spidery wiring inside little (and sometimes rather large) boxes, so that all the astronaut crew needed to worry about would be exchanging one box for another. This forward-thinking would prove to be critical to the success of Hubble’s five servicing missions.

Initial Difficulties

Hubble was launched and deployed successfully in April 1990, its orbital release a historic action in and of itself. But then the problems began. Not only was Hubble returning blurry images, but it was also having trouble locking onto the right guide stars — the markers that help Hubble stay locked on an object. “The spherical aberration, the issue that caused the blurry images, was really just one of multiple problems,” said Larry Dunham, the Chief Systems Engineer for Flight Systems for Hubble who has worked on the telescope from its very inception — over 30 years. “But we were still doing better science in this field than had ever been done before. We just knew it could be even better.”

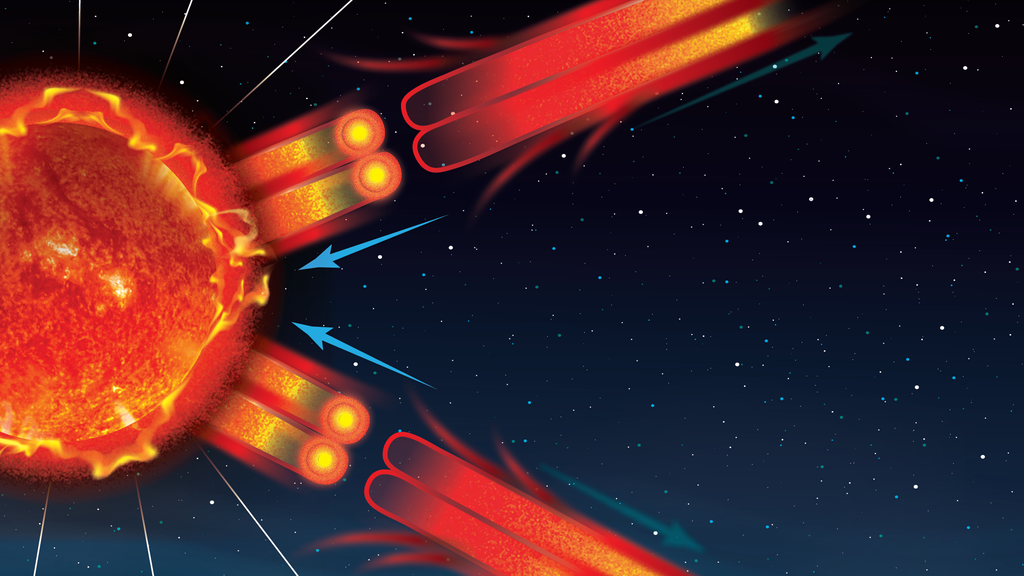

Dunham chaired a group called the Guide Star Acquisition Working Group. He said that his group was concerned with the blurry images problem, but that they remained concentrated on adjusting Hubble’s pointing capabilities so that the telescope could continue to produce scientific results. These capabilities were partially inhibited by a flexing of the solar arrays caused by drastic temperature changes during orbit.

“We developed software to counteract erratic movements from our solar arrays,” said Dunham. “Our group was responsible for essentially keeping Hubble pointed in the direction we wanted, so we worked to correct what we could.”

Simultaneously, a task force of engineers and scientists assembled to diagnose the aberration issue, find a solution and restructure the first servicing mission around fixing the predominant problems.

“When we began getting pictures from the Wide Field Planetary Camera and they looked weird, it just triggered something in me, and I just could not ignore the problem,” said Sandra Faber, an astrophysicist who was recruited as a team lead to determine the cause of Hubble’s blurry images. “I was living and breathing this problem every day... I couldn’t sleep, actually. I remember I would go to bed at 1 or 2 in the morning, very uncharacteristic of me. I would just lie in bed and these thoughts would revolve in my mind... what could be wrong, and a task list for tomorrow.”

Faber and her team worked incessantly to understand the problem with certainty. They constructed hypotheses, made models and tested their theories until they arrived at the solution: the mirror had been incorrectly ground, resulting in an imperfection less than the width of a human hair.

“It was the most complicated emotional moment of my life, because it was so good and so bad at the same time,” said Faber, lamenting the interplay of triumph in solving the problem and simultaneous dismay at the problem itself. “We were optimistic about it, though. At a minimum, we could credibly argue as scientists that the telescope could do a lot of very good work while the Hubble repair mission was designed and implemented.”

Servicing Mission One (SM1)

As astronauts Richard Covey, Kenneth Bowersox, Kathryn Thornton, Story Musgrave, Claude Nicollier, Jeff Hoffman and Tom Akers captured Hubble in orbit and moved it into the shuttle bay for repair, the world watched a historic event unfold.

“The American public had never seen a mission like this. You go up, you grab the telescope, and for a week, you’re watching these astronauts going out in spacesuits, doing five spacewalks, taking hardware out and putting hardware in, and it was just fascinating,” said Dunham. “The spacewalks all started after 10 p.m., and people were staying up into the night watching it on TV. That was just inspiring.”

Hubble’s servicing mission was imperative for many reasons outside of merely restoring its capabilities. The implications of failure stretched far into the future, as NASA was gearing up to begin building a permanent, orbiting laboratory, now known as the International Space Station.

“Everybody knew it was important,” said Thornton, who engaged in multiple spacewalks to repair the telescope during the mission. “Hubble is a national treasure. We were planning at the time to build the space station by hand. If we couldn’t fix Hubble, it was going to be hard to build the space station by the same method.”

Thornton maintains, however, that the astronauts themselves were largely shielded from the pressure of the mission. “In the end, we just did our jobs,” said Thornton. “We trained extensively, memorized procedures, imagined doing it up there. We took each task one at a time, and I would say it went very much according to plan.”

Hubble’s Impact on Servicing and Scientific Innovation

Necessity is the mother of invention, and the pioneering nature of Hubble’s servicing missions warranted the ingenuity of new procedures and new tools made for highly specific tasks. Specialized power tools helped astronauts use the right amount of torque in microgravity, and layers of protective hard plastic covered screws that needed to be removed, keeping them from floating off into space or falling into the spacecraft.

“We [NASA] did a lot of designing of tools specifically for Hubble,” said Dunham. “Those tools are being used now in all kinds of other places in other ways. Our hardware has evolved over time because we’ve learned from the astronauts what works best for them. We had to design all those things from scratch. I think that knowledge has been able to be used a lot of different places.”

Hubble was the birthplace for many of these new procedures, and changed our idea as a nation of what it means to have a presence in space. “We really expanded our human capability to go up there and repair things, doing things that we thought may not have been possible,” said Thornton. “With each mission, I think we expanded our knowledge of servicing in space. Each mission was more complex than the one before.”

“The whole concept of astronauts treating space as a workplace, where they can go for a week or longer and work... I think we developed that concept on Hubble, and we learned a lot from that,” said Dunham. “That’s the kind of expertise they’ll need for those missions that will travel to the Moon and to Mars.”

Hubble has swept us into a new era of understanding our universe. The advancements and knowledge we have gained from its data and images are unparalleled, and our continuously developing capabilities in servicing have allowed Hubble to remain in orbit for more than a generation. Some people have been able to center their entire careers on Hubble, and the telescope’s vast swaths of data are now influencing the next generation of scientists, engineers and explorers.

“My oldest daughter was 11 years old when we did that first servicing mission,” said Thornton. “She went on to get her doctorate in physics and astronomy using Hubble data, and now she is a professor.”

After 25 years of servicing innovation and 28 years in orbit, Hubble’s vitality, color, vision and scientific prowess remain unmatched. As NASA pursues its mission to uncover further mysteries of the universe, Hubble will endure as the cornerstone of astronomical discovery and human determination.

To learn more about the Hubble Space Telescope, SM1, later servicing missions, images captured by Hubble and more, visit nasa.gov/hubble.