6 min read

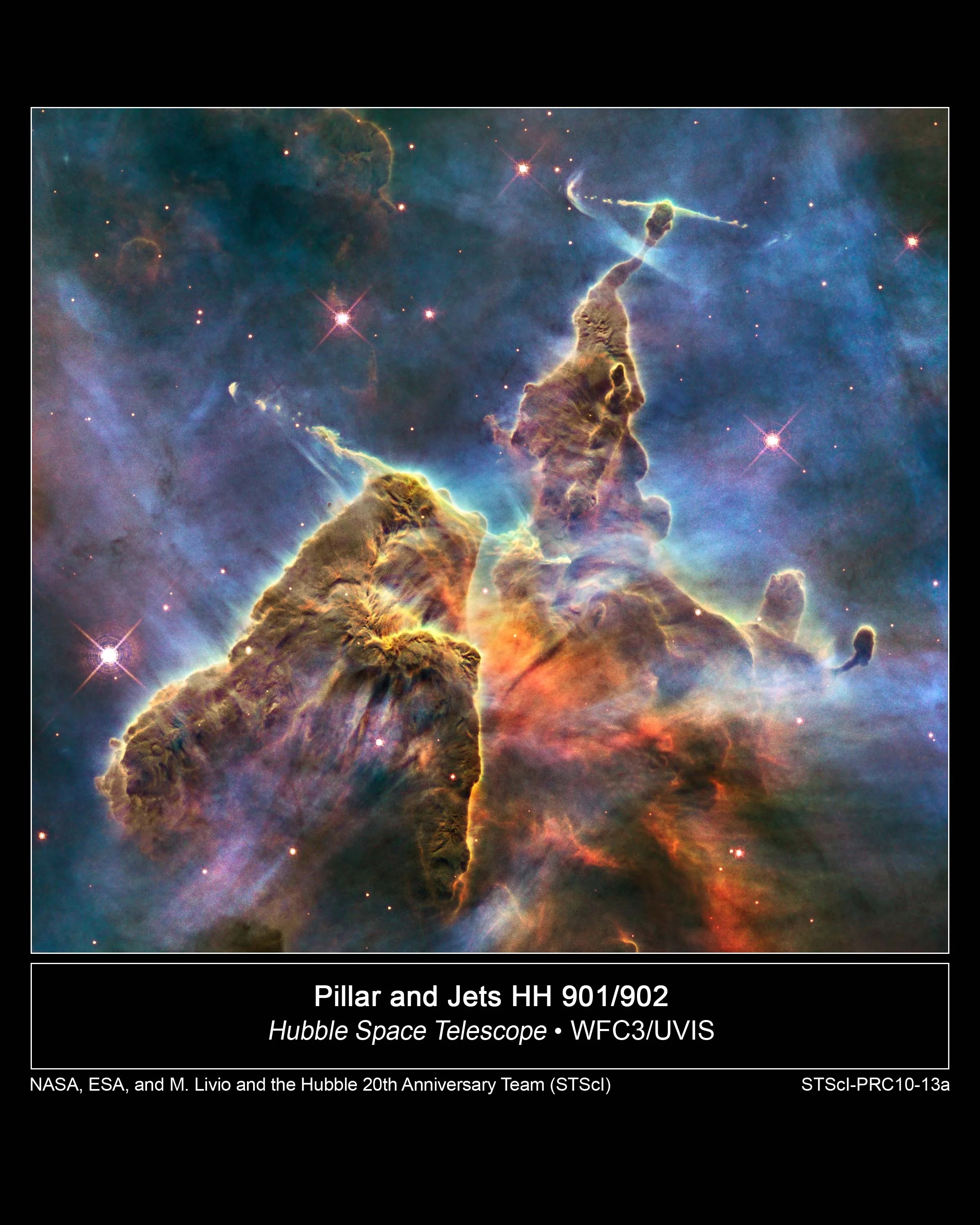

This Hubble photo is of a small portion of one of the largest-seen star-birth regions in the galaxy, the Carina Nebula. Towers of cool hydrogen laced with dust rise from the wall of the nebula. The pillar is also being pushed apart from within, as infant stars buried inside it fire off jets of gas that can be seen streaming from towering peaks. Credit: NASA, ESA, and M. Livio and the Hubble 20th Anniversary Team (STScI)

An image of the galaxy NGC 4603, taken by the Hubble Space Telescope in 1996 and 1997. Astronomers measured this galaxy to determine its distance to be 108 million light years. It was the most distant galaxy used in Hubble's key project to determine the age of the universe.Photo credit: NASA

The Hubble Space Telescope was last seen by human eyes on STS-125, the last serving mission by a space shuttle. The astronauts installed new instruments and components so the telescope can continue operating for years to come. Photo credit: NASA

Space shuttle Discovery roared into orbit April 24, 1990, with a most precious cargo, NASA's Hubble Space Telescope. In the two decades since, teams of astronauts working from other shuttles repaired the orbiting eye on the universe and extended its abilities far beyond what was thought possible for longer than many thought realistic.

Hubble, named for groundbreaking astronomer Edwin Hubble, repaid the commitment with some of the most dazzling images the world has seen, along with fresh data that answered a wealth of questions and led to many new ones. The telescope's observations allowed astronomers to set the age of the universe at about 13.7 billion years with a high degree of certainty.

"I never believed in 1990 that the Hubble would end up this great," said Ed Weiler, NASA associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate and chief scientist for the Hubble program when it launched. "It's changed a lot of thinking and it's changed a lot of what I learned 30 years ago in grad school."

Hubble's discoveries stretch over most aspects of astronomy, but its highlights include proving massive black holes exist and defining the age of the universe. It also proved the existence of something no one has seen -- dark energy.

"Nobody ever knew it existed before Hubble," said Jon Grunsfeld, an astronaut and astronomer who worked on Hubble during two shuttle missions.

The telescope's most unique element, though, is its orbit -- a perch so high above the planet that its pictures are not warped or distorted by the air currents, moisture and other effects from Earth's atmosphere.

"It's that extreme clarity that gives us the feeling we've traveled out into space to see these objects," Grunsfeld said. "It really is our time machine."

From more than 300 miles in space, Hubble looked back in time, showing astronomers what embryonic galaxies looked like almost 14 billion years ago. In some cases, Hubble's instruments picked up light that left stars only 600 million years after the Big Bang."We're seeing the universe as it was perhaps as a toddler," Grunsfeld said.

An image that is perhaps Hubble's most famous, known as the Hubble Deep Field, was made when the telescope was pointed at a small sliver of space in the constellation Ursa Major, which appeared black and empty. Hubble found it brimming with young galaxies and stars in a kind of photographic time capsule from the universe. Astronomers called it a baby picture of space.

The Hubble Ultra Deep Field built on that image in 2003 and 2004 when it used new instruments to pick out galaxies in another section of the sky which would have been too faint for Hubble's previous equipment to detect.

"We always discover things that we never even imagine," Grunsfeld said. "The universe is always more interesting than we give it credit for."

Some of the most notable discoveries were almost lost because Hubble was launched with a tiny flaw in its main mirror. Although the mirror was ground too flat by less than the width of a human hair, that was enough to throw off the focus.

"Little did we know we were launching a telescope that had a mirror that was slightly misshapen," Weiler said. "But we found a way to fix it, which we did, which the astronauts did, in 1993 and for the past 17 years Hubble's been filling the textbooks with new science."Starting with STS-61 in 1993, five teams of astronauts worked on the telescope from the space shuttle. The first installed a set of small mirrors that acted like a contact lens to clarify Hubble's vision. Since then, new instruments have been added, along with new components. Taken together, the servicing missions added years to Hubble's life.

"When we launched it in 1990, we were hoping to get 10 to 15 years out of it," Weiler said. "We're now talking about the 20th anniversary, so we're talking about five years of dividends on our investment, and we should be able to get at least another five years and maybe another seven, eight or nine years."

Astronomers were not the only ones pleased with the life extension. The 12 1/2-ton space telescope reached into the mind and spirit of the general public in an unprecedented way. Images from the telescope have made their way onto stamps, album covers and even into art exhibits.

"I think the unique thing about the Hubble is that it's truly brought science to the general public, especially the school kids," Weiler said. "It's still the most powerful telescope that humans have the ability to use and it has been since it was launched."As much as Hubble became a cornerstone for astronomy, it was also the first element of NASA's Great Observatories program which produced four telescopes that looked at the different kinds of light in the universe. The Hubble was designed to see visible light, which is the same light people see. So Hubble's pictures show the universe as it appears to the human eye.

The Compton Gamma Ray Observatory launched in 1991 to detect gamma ray bursts, some of the most energetic particles known. The Chandra X-Ray Observatory was launched in 1999 and surveyed the universe for invisible x-rays. Lastly, the Spitzer Space Telescope went into space in 2003 to look at the cooler heart of space, including dust clouds that are the nursery for stars. The Spitzer was the only NASA “Great Observatory” not launched on a shuttle. Instead, it rode a Delta II.

None of the observatories was meant to study space by themselves. Astronomers instead used one telescope's findings to study it with the others to form a nearly complete picture of a celestial place across the spectrum of light. Ground-based telescopes, which continue to grow in size and sophistication, are also used to study or confirm findings.

Although there won't be any more servicing missions by the shuttle, Weiler and Grunsfeld said the telescope is ready to make more discoveries.

"The telescope still looks in great shape," Grunsfeld said. "It's just a thrill to work on what is by many measures the most productive scientific instrument ever created by humans."

Steven Siceloff

NASA's John F. Kennedy Space Center