4 min read

Detailed analysis of two continent-sized storms that erupted in Jupiter's atmosphere in March 2007 shows that Jupiter's internal heat plays a significant role in generating atmospheric disturbances.

Scientists around the globe have observed an astonishing and rare change in Jupiter's atmosphere -- a huge disturbance churning in the middle northern latitudes of the planet as two giant storms erupted.

Jupiter's winds are the strongest at middle northern latitudes, reaching about 600 kilometers per hour (370 miles per hour). Similar phenomena occurred in 1975 and 1990, but this event has never been observed before with high-resolution modern telescopes.

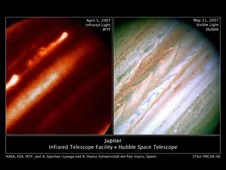

The storm eruption was captured in late March 2007 by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility in Hawaii and telescopes in the Canary Islands (Spain). A network of smaller telescopes around the world also supported these observations.

An international team coordinated by Agustín Sánchez-Lavega from the Universidad del País Vasco in Spain presents their findings about this event in the January 24 issue of the journal Nature. The team monitored the new eruption of cloud activity and its evolution with unprecedented resolution.

"Fortuitously, we captured the onset of the disturbance with Hubble, while monitoring the planet to support the New Horizons flyby observations of Jupiter in its route to Pluto. We saw the storm grow rapidly since its beginning, from about 400 kilometers [250 miles] to more than 2,000 kilometers [1,245 miles] in size in less than one day," said Sánchez-Lavega.

The atmosphere of the gaseous giant planet Jupiter is always turbulent. Its circulation is dominated by a pattern of cloud bands alternating with latitude, and by a persistent system of jet streams, both of unknown origin. Changes in the cloud bands are sometimes violent, starting from a localized eruption and followed by the development of a planetary-scale disturbance. The nature of these disturbances and the power source for these jets remains a controversial matter among planetary scientists and meteorologists. The phenomena could be powered by the sun, as is Earth, by the strong internal heat source emanating from Jupiter's interior, or by a combination of both.

According to the analysis, the bright plumes were storm systems triggered in Jupiter's deep water clouds that vigorously moved upward in the atmosphere and injected a fresh mixture of ammonia ice and water about 30 kilometers (20 miles) above the visible clouds. The storms moved in the peak of a jet stream in Jupiter's atmosphere at 600 kilometers per hour (375 miles per hour). They disturbed the jet and formed in their wake a turbulent planetary-scale disturbance containing red cloud particles.

"The infrared images distinguish the plumes from lower-altitude clouds and show that the plumes are lofting ice particles higher than anyplace else on the planet," said Glenn Orton of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. Orton is second author of the paper.

In spite of the energy deposited and the stirring and turmoil generated by the storms, the jet remained practically unchanged when the disturbance ceased, keeping steady against these storms. Models of the disturbance indicate that the jet stream extends deep in the buried atmosphere of Jupiter, more than 100 kilometers (62 miles) below the cloud tops where most sunlight is absorbed.

"This confirms previous findings by the Galileo probe when it descended through Jupiter's upper atmosphere in December 1995. Although both regions are meteorologically different, all the evidence points to a deep extent for Jupiter's jets and suggest that the internal heat power source plays a significant role in generating the jet," said Sánchez-Lavega.

A comparison of this disturbance with the two previous events in 1975 and 1990 shows surprising similarities and coincidences, all of which remain unexplained. All three eruptions occurred with a periodic interval of about 15 to 17 years. The plumes always appear in the jet peak; the disturbance erupted with exactly two plumes. Finally, the plumes moved with the same speed of the jet peak in all three events. Understanding this outbreak could be the key to unlocking the mysteries buried in the deep Jovian atmosphere.

Understanding these phenomena is important for Earth's meteorology, where storms are present everywhere and jet streams dominate the atmospheric circulation. In this way, Jupiter represents a natural laboratory where atmospheric scientists study the nature and interplay of the intense jets and severe atmospheric phenomena.

JPL is managed for NASA by the California Institute of Technology. The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and the European Space Agency.

Related links:

Media contact: Carolina Carnalla-Martinez

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif

818-354-9382

carnalla@jpl.nasa.gov

2008-013