Astronomers using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope may have found evidence for a cluster of young, blue stars encircling one of the first intermediate-mass black holes ever discovered. Astronomers believe the black hole may once have been at the core of a now-disintegrated unseen dwarf galaxy. The discovery of the black hole and the possible star cluster has important implications for understanding the evolution of supermassive black holes and galaxies.

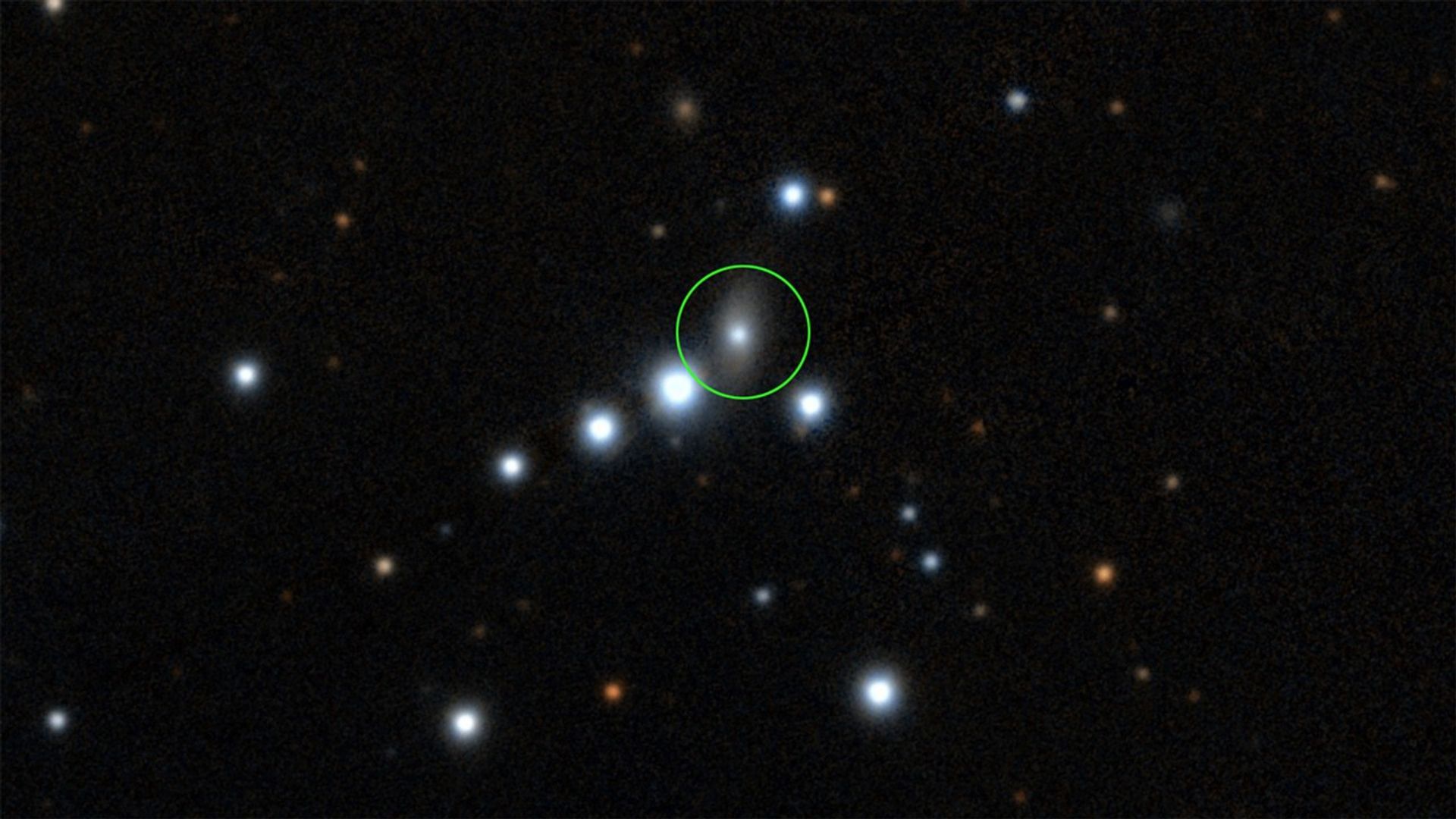

This spectacular edge-on galaxy, called ESO 243-49, is home to an intermediate-mass black hole that may have been stripped off of a cannibalized dwarf galaxy. The estimated 20,000-solar-mass black hole lies above the galactic plane. This is an unlikely place for such a massive back hole to exist, unless it belonged to a small galaxy that was gravitationally torn apart by ESO 243-49. The circle identifies a unique X-ray source that pinpoints the black hole. The X-rays are believed to be radiation from a hot accretion disk around the black hole. The blue light not only comes from a hot accretion disk, but also from a cluster of hot young stars that formed around the black hole. The galaxy is 290 million light-years from Earth. Hubble can’t resolve the stars individually because the suspected cluster is too far away. Their presence is inferred from the color and brightness of the light coming from the black hole’s location. (Credit: NASA; ESA; and S. Farrell, Sydney Institute for Astronomy, University of Sydney) › Larger image |

Astronomers know how massive stars collapse to form black holes but it is not clear how supermassive black holes, which can weigh billions of times the mass of our sun, form in the cores of galaxies. One idea is that supermassive black holes may build up through the merger of smaller black holes.

Sean Farrell of the Sydney Institute for Astronomy in Australia discovered a middleweight black hole in 2009 using the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton X-ray space telescope. Known as HLX-1 (Hyper-Luminous X-ray source 1), the black hole has an estimated weight of about 20,000 solar masses. It lies towards the edge of the galaxy ESO 243-49, 290 million light-years from Earth.

Farrell then observed HLX-1 simultaneously with NASA’s Swift observatory in X-ray and Hubble in near infrared, optical and ultraviolet wavelengths. The intensity and the color of the light may indicate the presence of a young, massive cluster of blue stars, perhaps 250-light-years across, encircling the black hole. Hubble can’t resolve the stars individually because the suspected cluster is too far away. The brightness and color is consistent with other clusters of stars seen in other galaxies, but some of the light may be coming from the gaseous disk around the black hole.

“Before this latest discovery, we suspected that intermediate-mass black holes could exist, but now we understand where they may have come from,” Farrell said. “The fact that there seems to be a very young cluster of stars indicates that the intermediate-mass black hole may have originated as the central black hole in a very-low-mass dwarf galaxy. The dwarf galaxy might then have been swallowed by the more massive galaxy, just as happens in our Milky Way.”

From the signature of the X-rays, Farrell’s team knew there would be some blue light emitted from the high temperature of the hot gas in the disk swirling around the black hole. They couldn’t account for the red light coming from the disk. It would have to be produced by a much cooler gas, and they concluded this would most likely come from stars. The next step was to build a model that added the glow from a population of stars. These models favor the presence of a young massive cluster of stars encircling the black hole, but this interpretation is not unique, so more observations are needed. In particular, the studies led by Roberto Soria of the Australian International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research, using data from Hubble and the ground-based Very Large Telescope, show variations in the brightness of the light that a star cluster couldn’t cause. This indicates that irradiation of the disk itself might be the dominant source of visible light, rather than a massive star cluster.

“What we can definitely say with our Hubble data is that we require both emission from an accretion disk and emission from a stellar population to explain the colors we see,” said Farrell.

Such young clusters of stars are commonly found inside galaxies like the host galaxy, but not outside the flattened starry disk, as found with HLX-1. One possible scenario is that the HLX-1 black hole was the central black hole in a dwarf galaxy. The larger host galaxy may then have captured the dwarf. In this conjecture, most of the dwarf’s stars would have been stripped away through the collision between the galaxies. At the same time, new, young stars would have formed in the encounter. The interaction that compressed the gas around the black hole would then have also triggered star formation.

Farrell theorizes that the possible star cluster may be less than 200 million years old. This means that the bulk of the stars formed following the dwarf’s collision with the larger galaxy. The age of the stars tells how long ago the two galaxies crashed into each other.

Farrell proposed for more observations this year. The new findings are published in the February 15 issue of the Astrophysical Journal. Soria and his colleagues have published their alternative conclusions in the January 17 online issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and the European Space Agency. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Md., conducts Hubble science operations. STScI is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., in Washington, D.C.

For more images and information about HLX-1, visit: