If you are reading this blog more than likely you’ve heard that despite early indications of a successful core acquisition during our first attempt on Aug. 6, there was no rock in the sample tube. And that given our unsuccessful search around the rover for a “dropped core”, the only reasonable interpretation is that the rock fragmented to dust or sand as we rotary-percussed into it.

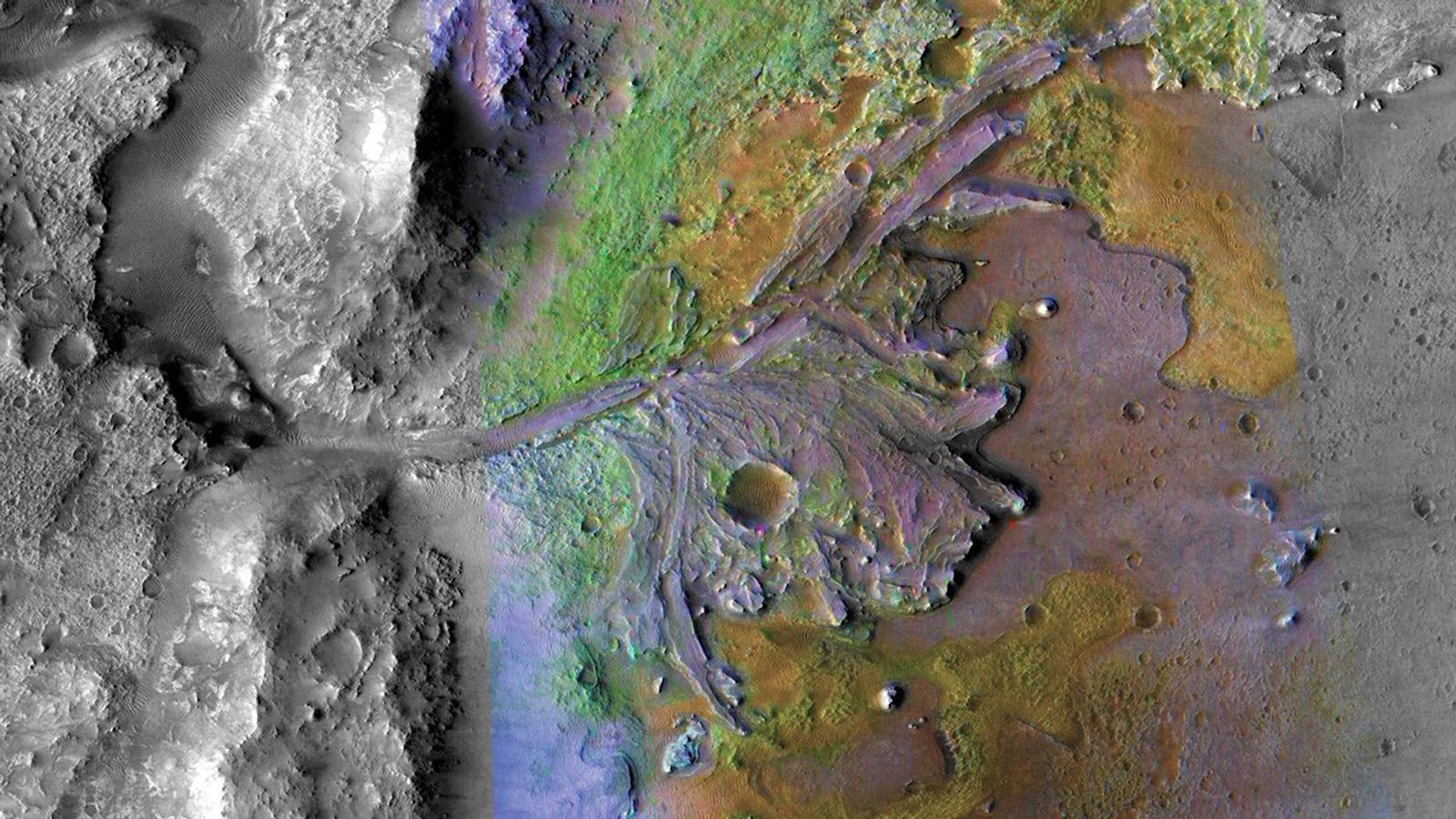

Our target for this first attempt, which we called Roubion, was on one of the flat polygonal-shaped rocks that we have seen all along the rover’s traverse so far. These “paver stone” rocks are an important sampling target because, among other things, this Crater Floor-Fractured Rough (CFFR) geologic unit could contain the lowest and oldest rocks we come across in the crater – important info for when we attempt to figure out the geologic history of the crater.

Fortunately, there are similar paver stones available in this area which we feel have a better chance of being compatible with of our sampling system. Since at present our plan is to drive back the way we came, there is a high probability we will revisit sampling of these rocks at a later date. More on them in a minute.

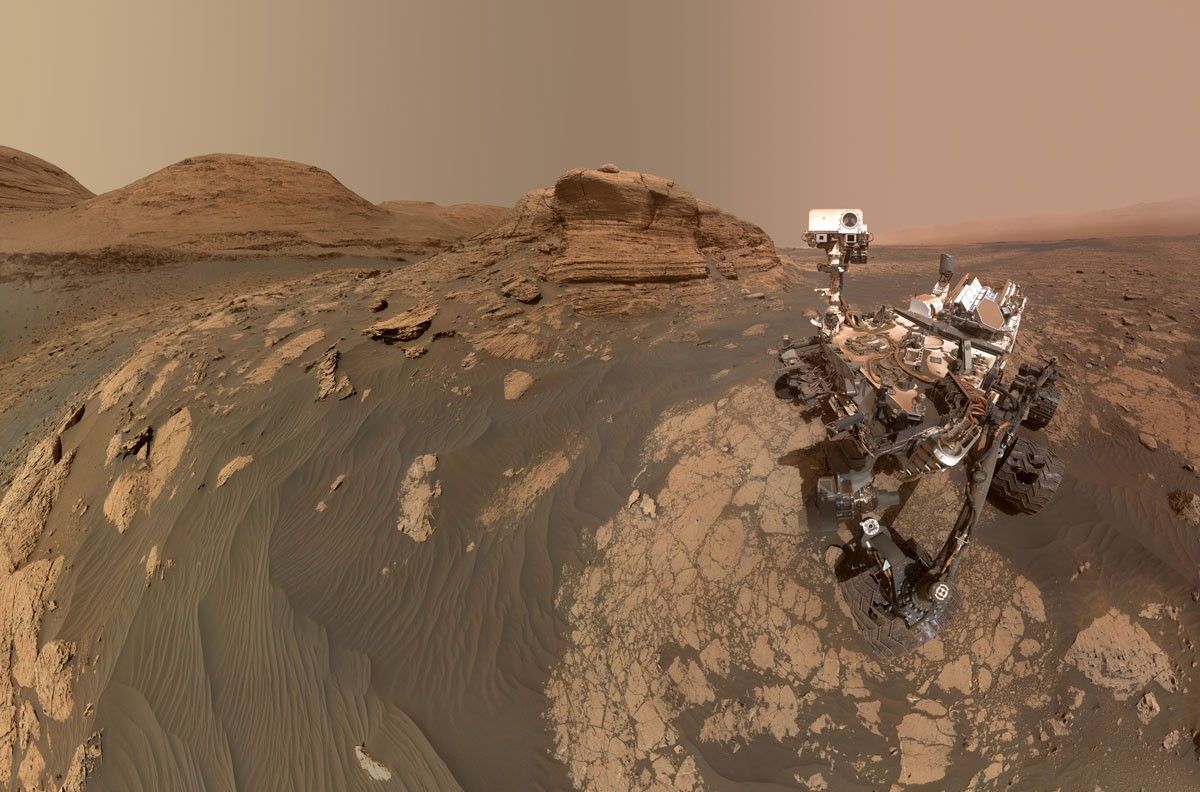

In response to not collecting a core, we searched for rocks as different as possible from the pavers to allow us to test the idea that Roubion was just a poorly behaved rock. And right near the rover we identified excellent candidates. As of this writing, we’re only 150 meters away from a very promising location we’re calling Citadelle (French for castle). The spot is part of an about 400-meter-long ridgeline called Artuby that contains rock outcrops and meter-scale boulders, some displaying intriguing layering. Orbital imagery shows that the boulders at Citadelle are actually part of an extensive outcrop on the summit and back side of the ridge.

The boulders of Citadelle provide good targets for another coring attempt because they are very solid in appearance, a conclusion supported by the fact that they stand high in the landscape even after eons of erosive action. They also have high science value in a potential crater floor sample suite. I expect we’ll pick out a target on one of these boulders and begin the planning for our next coring activity next week, with our next sampling attempt around the end of the month.

After Citadelle, we’ll have to figure out where to head next. More than likely, we’ll continue our westward trek toward South Seítah where we expect to find very different rock outcrops and boulders to scrutinize. After that, we head out the way we came, and possibly have another go at coring CFFR.

Why would we try again with CFFR if we failed the first time? All Martian paver stones are not created equal. The most common variety are light colored and heavily wind-polished “whalebacks” that protrude upward from the sandy Martian surface. The rover saw plenty of these near the Butler landing site. A second variety can be found further south of Butler. These pavers are more orange, and are clearly suffering erosion -- they’re literally falling apart.

It was these second (more orange) paver stones we chose for our first sample attempt because they provided us an excellent flat and smooth target for first coring. But in hindsight, this weathered rock may have been doing all it could to tell us just how uncooperative it was going to be to our sampling system. The orange color is from iron being leached from primary minerals and reprecipitated as iron oxide. Basically, rusting rock! The orange pavers also had another ‘tell’ which we did not pick up on -- all those fragments of rock lying about suggest less structural integrity than the whalebacks. My suspicion is that had we attempted coring on a whaleback the result would have been different.

But that’s Mars. We have a plan, a clear road ahead and a rover with an amazing sample collection system ready to show us what it can do. All we need is a couple weeks and a well-behaved rock.

Written by Kenneth Farley, Project Scientist at Caltech