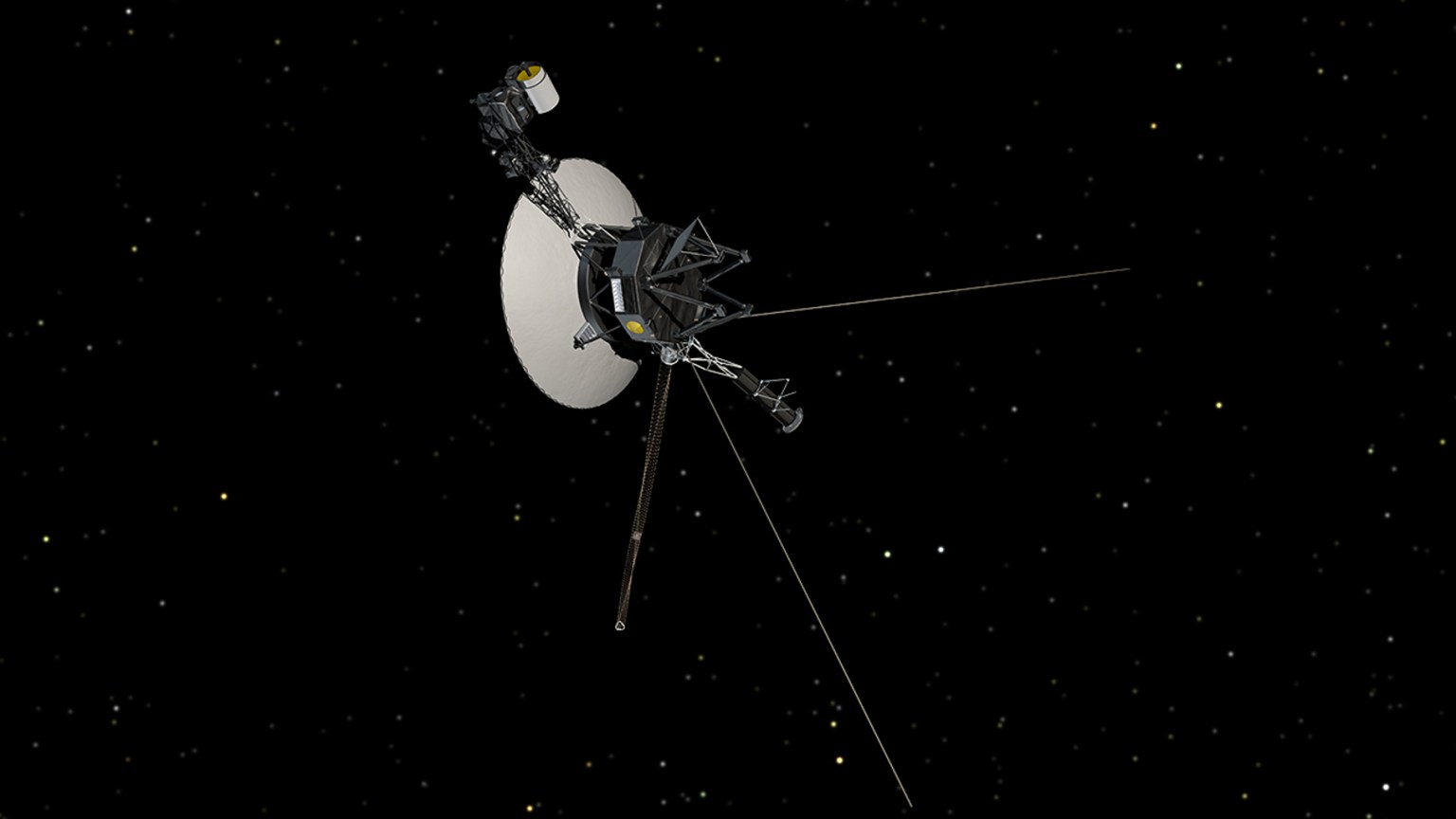

SAN FRANCISCO, Calif. – NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft has followed its twin, Voyager 1, into the solar system's final frontier, a vast region at the edge of our solar system where the solar wind runs up against the thin gas between the stars.

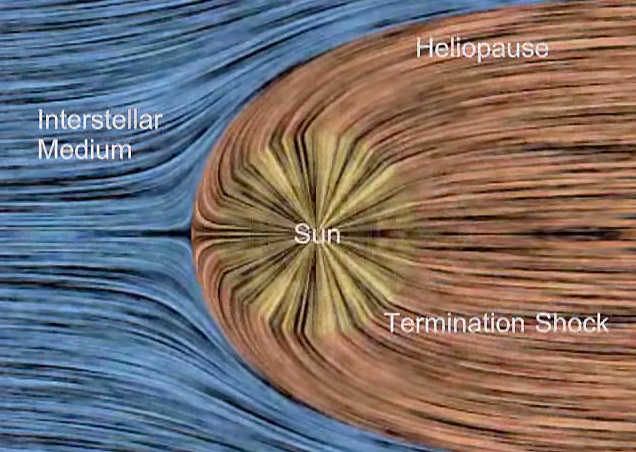

However, Voyager 2 took a different path, entering this region, called the heliosheath, on Aug. 30, 2007. Because Voyager 2 crossed the heliosheath boundary, called the solar wind termination shock, about 16 billion kilometers (10 billion miles) away from Voyager 1 and almost 1.6 billion kilometers (a billion miles) closer to the sun, it confirmed that our solar system is "squashed" or "dented"– that the bubble carved into interstellar space by the solar wind is not perfectly round. Where Voyager 2 made its crossing, the bubble is pushed in closer to the sun by the local interstellar magnetic field.

"Voyager 2 continues its journey of discovery, crossing the termination shock multiple times as it entered the outermost layer of the giant heliospheric bubble surrounding the sun and joined Voyager 1 in the last leg of the race to interstellar space," said Voyager Project Scientist Edward Stone of the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, Calif. Results on the Voyager 2 shock crossing from the entire Voyager science team are being presented at the Fall 2007 meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

The solar wind is a thin gas of electrically charged particles (plasma) blown into space by the sun. The solar wind blows in all directions, carving a bubble into interstellar space that extends past the orbit of Pluto. This bubble is called the heliosphere, and Voyager 1 was the first spacecraft to explore its outer layer, when it crossed into the heliosheath in December 2004. As Voyager 1 made this historic passage, it encountered the shock wave that surrounds our solar system called the solar wind termination shock, where the solar wind is abruptly slowed by pressure from the gas and magnetic field in interstellar space.

Even though Voyager 2 is the second spacecraft to cross the shock, it is scientifically exciting for a couple of reasons. The Voyager 2 spacecraft has a working plasma science instrument that can directly measure the velocity, density and temperature of the solar wind. This instrument is no longer working on Voyager 1, and estimates of the solar wind speed had to be made indirectly. Secondly, Voyager 1 may have had only a single shock crossing, and it happened during a data gap. But Voyager 2 had at least five shock crossings over a couple of days (the shock "sloshes" back and forth like surf on a beach, allowing multiple crossings), and three of them are clearly in the data. They show us an unusual shock.

In a normal shock wave, fast-moving material slows down and forms a denser, hotter region as it encounters an obstacle. However, Voyager 2 found a much lower temperature beyond the shock than was predicted. This probably indicates that the energy is being transferred to cosmic ray particles that were accelerated to high speeds at the shock.

"The important new data describing the termination shock are still being pondered, but it is clear that Voyager has once again surprised us," said Eric Christian, Voyager Program Scientist at NASA Headquarters, Washington.

The two Voyager spacecraft will be the only source of local observations of this distant but highly interesting region for years to come. But in the summer of 2008, NASA will be launching a mission specifically designed to globally image the termination shock and heliosheath remotely from Earth orbit. The Interstellar Boundary Explorer, led by David McComas of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, will use energetic neutral atoms to create all-sky maps at various energies of the interaction of the heliosphere with interstellar space. Energetic neutral atoms are formed when energetic electrically-charged particles "steal" an electron from another particle. Once neutral, they travel straight, unaffected by the solar magnetic field. The Interstellar Boundary Explorer will detect some of the particles that happen to be headed towards Earth, and the number and energy of the particles coming from all different directions will tell us much more about the overall structure of the interaction between the heliosphere and interstellar space.

The Voyagers were built by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., which continues to operate both spacecraft.

For images, refer to: https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/voyager/termination_shock.html.

For more information on the Voyager mission see: https://www.nasa.gov/voyager and https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/.