After starting science operations in February, Japan-led XRISM (X-ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission) studied the monster black hole at the center of galaxy NGC 4151.

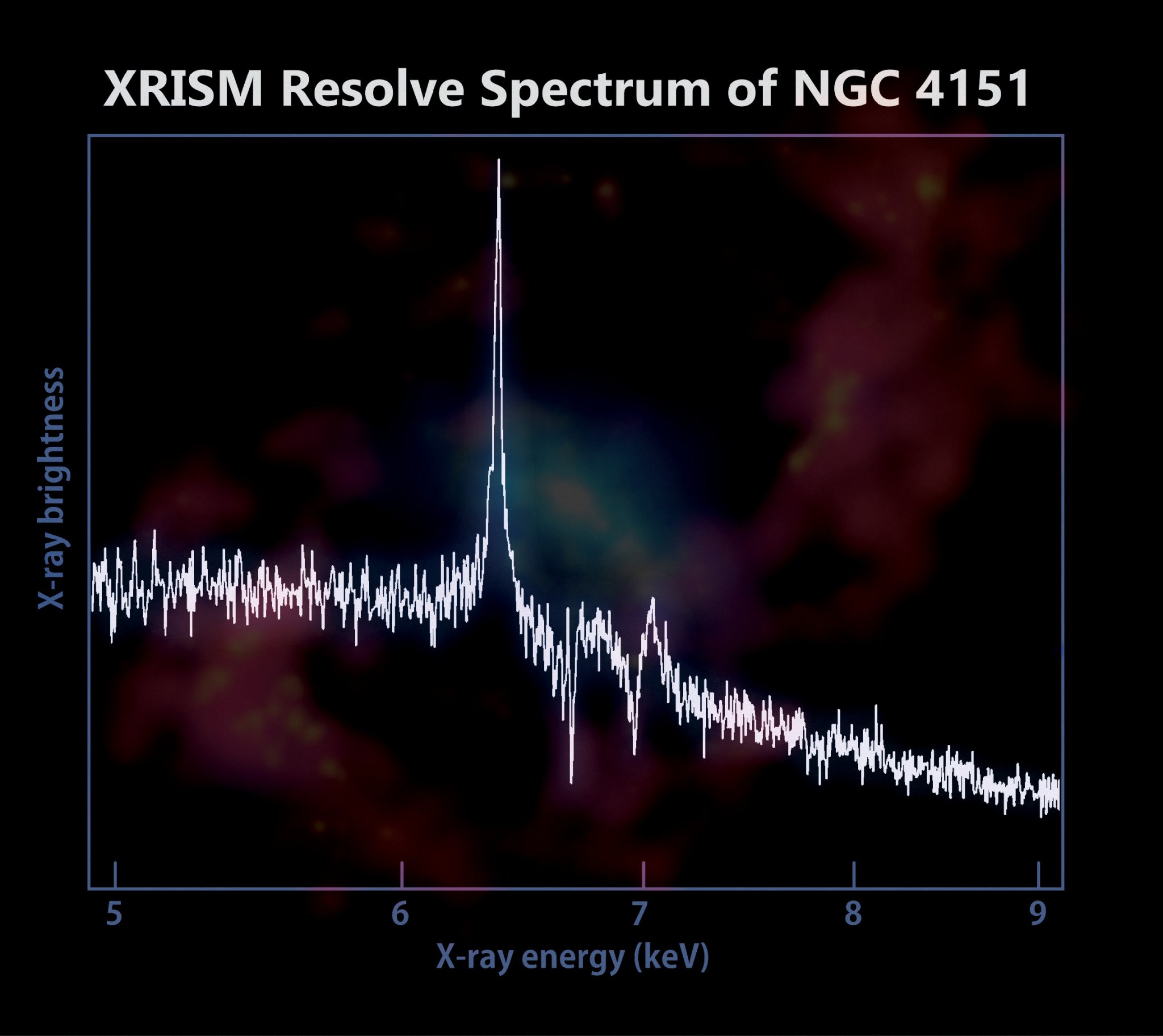

“XRISM’s Resolve instrument captured a detailed spectrum of the area around the black hole,” said Brian Williams, NASA’s project scientist for the mission at the agency’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “The peaks and dips are like chemical fingerprints that can tell us what elements are present and reveal clues about the fate of matter as it nears the black hole.”

XRISM (pronounced “crism”) is led by JAXA (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency) in collaboration with NASA, along with contributions from ESA (European Space Agency). It launched Sept. 6, 2023. NASA and JAXA developed Resolve, the mission’s microcalorimeter spectrometer.

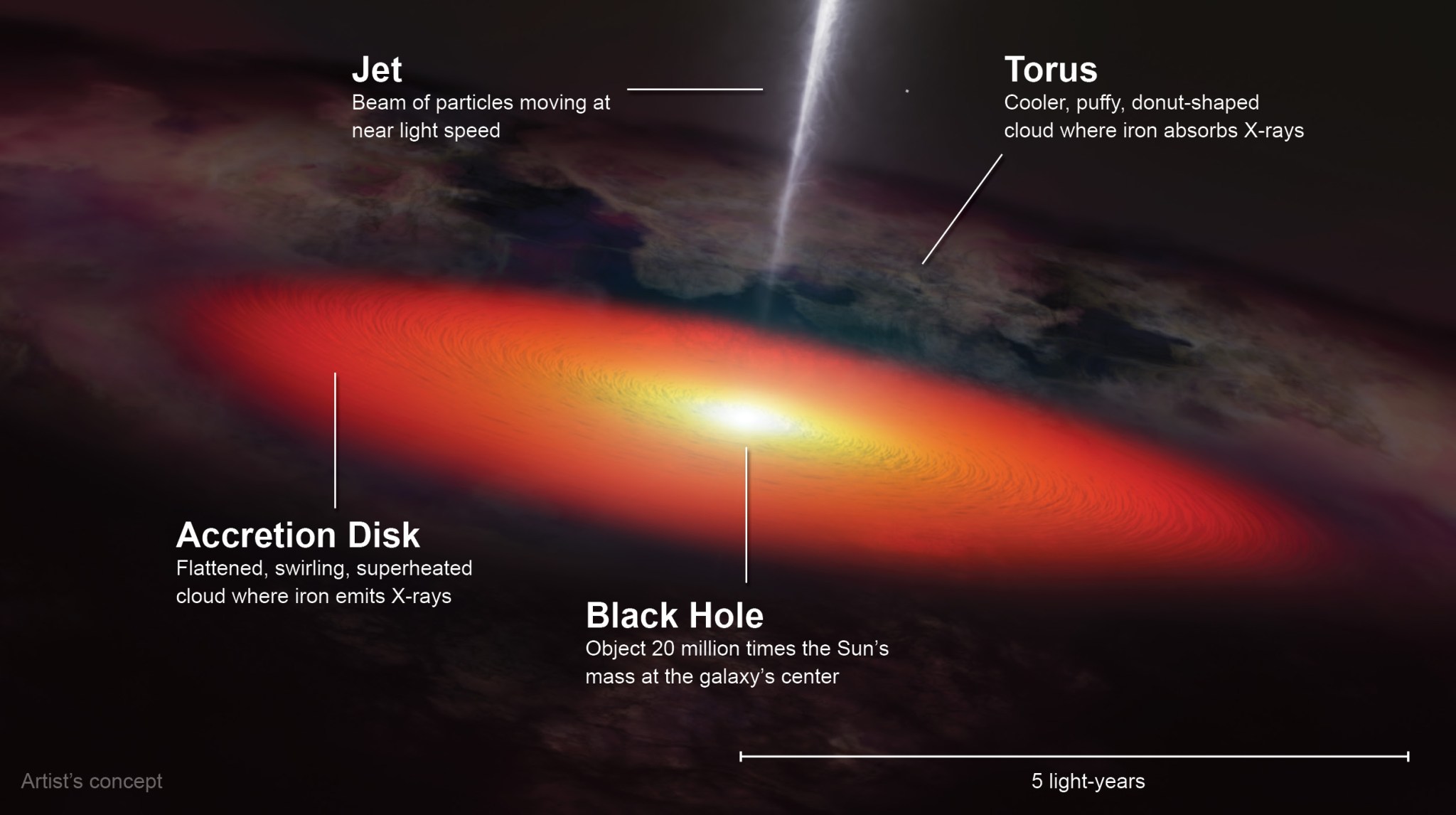

NGC 4151 is a spiral galaxy around 43 million light-years away in the northern constellation Canes Venatici. The supermassive black hole at its center holds more than 20 million times the Sun’s mass.

The galaxy is also active, which means its center is unusually bright and variable. Gas and dust swirling toward the black hole form an accretion disk around it and heat up through gravitational and frictional forces, creating the variability. Some of the matter on the brink of the black hole forms twin jets of particles that blast out from each side of the disk at nearly the speed of light. A puffy donut-shaped cloud of material called a torus surrounds the accretion disk.

In fact, NGC 4151 is one of the closest-known active galaxies. Other missions, including NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and Hubble Space Telescope, have studied it to learn more about the interaction between black holes and their surroundings, which can tell scientists how supermassive black holes in galactic centers grow over cosmic time.

The galaxy is uncommonly bright in X-rays, which made it an ideal early target for XRISM.

Resolve’s spectrum of NGC 4151 reveals a sharp peak at energies just under 6.5 keV (kiloelectron volts) — an emission line of iron. Astronomers think that much of the power of active galaxies comes from X-rays originating in hot, flaring regions close to the black hole. X-rays bouncing off cooler gas in the disk causes iron there to fluoresce, producing a specific X-ray peak. This allows astronomers to paint a better picture of both the disk and erupting regions much closer to the black hole.

The spectrum also shows several dips around 7 keV. Iron located in the torus caused these dips as well, although through absorption of X-rays, rather than emission, because the material there is much cooler than in the disk. All this radiation is some 2,500 times more energetic than the light we can see with our eyes.

Iron is just one element XRISM can detect. The telescope can also spot sulfur, calcium, argon, and others, depending on the source. Each tells astrophysicists something different about the cosmic phenomena scattered across the X-ray sky.

XRISM is a collaborative mission between JAXA and NASA, with participation by ESA. NASA’s contribution includes science participation from CSA (Canadian Space Agency).

By Jeanette Kazmierczak

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Media Contact:

Claire Andreoli

301-286-1940

claire.andreoli@nasa.gov

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.