Carolyn Shoemaker (1929-2021)

Astronomer

Editors’ Note: Carolyn Shoemaker was a world-renowned astronomer, and comet and asteroid hunter. She died on Aug. 13, 2021, at the age of 92. Carolyn was married to acclaimed geologist Eugene (Gene) Shoemaker (1928-1997). Together the pair made vast contributions to the study of asteroids and comets – including the co-discovery of history-making comet Shoemaker-Levy 9. Carolyn once said that it was impossible to write about much of her life without also discussing Gene in a major way, so this tribute also includes many of Gene’s accomplishments.

Education

Chico High School, Chico, California

Honorary Doctorate of Science

Northern Arizona University (1990)

Master’s Degrees in History and Political Science

Chico State College, now California State University, Chico

The Early Years

Carolyn Shoemaker never set out to be a scientist. But after her three children were grown, she wanted something new to do. So at the age of 51, she started a second career and became a world-renowned astronomer. Carolyn – along with her husband Gene Shoemaker and their colleague David Levy – co-discovered comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 on March 24, 1993. It was the first comet observed to be orbiting a planet – in this case, Jupiter – rather than the Sun. Jupiter’s tidal forces tore the comet apart and, eventually, the fragments collided with Jupiter between July 16 and June 22, 1994.

“Carolyn Shoemaker leaves us all with a legacy of inspiration and encouragement for people of all backgrounds and all ages, as we explore our solar system and beyond,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s Associate Administrator for the Science Mission Directorate.

While comet Shoemaker-Levy’s 9’s impact with Jupiter was dramatic, it was more than just a cosmic show. It gave scientists new insights into comets – and into Jupiter. The impact also was a wake-up call for scientists: If the comet had hit Earth instead of Jupiter, it could have created a global disaster. Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 helped lead to the creation of NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office.

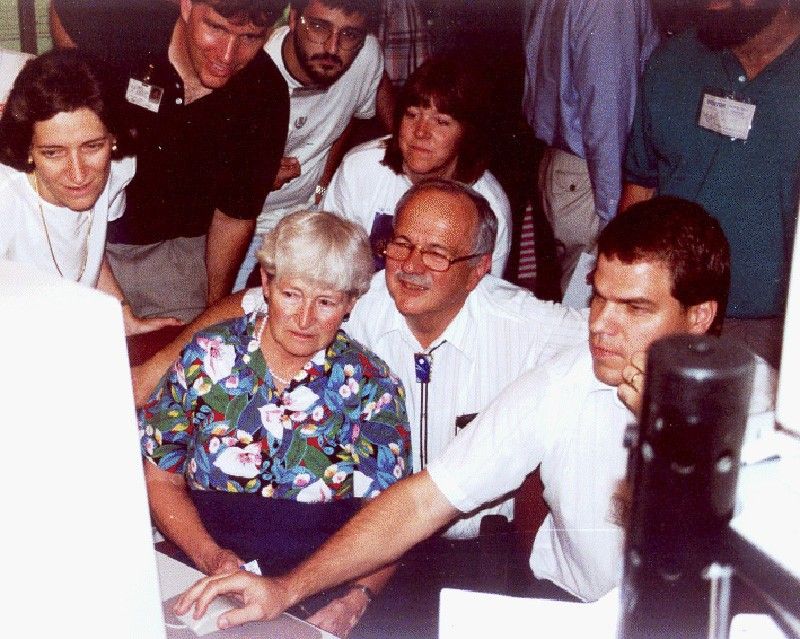

Carolyn Shoemaker also discovered or co-discovered dozens of other comets and hundreds of asteroids. She shared the story of how she became a scientist with NASA/JPL media producer Leslie Mullen in an interview on July 22, 2019. This tribute is based largely on that interview, and the podcast episode in which the interview was featured.

A Cosmic Love Story

Carolyn Jean Spellmann was born June 24, 1929, in Gallup, New Mexico. Her family moved to Chico, California, where she went to high school. By 1950 she had earned a master’s degree in history and political science from Chico State College, now California State University, Chico. She also had a teaching credential and a contract to teach seventh grade in Petaluma, California.

But before she left home to start teaching, fate intervened. Her brother’s wedding – and a camping trip that included her mother! – led to Carolyn’s marriage to a young geologist named Gene Shoemaker. And that marriage eventually led to her career as a comet and asteroid hunter.

Carolyn met Gene Shoemaker in 1948 when Gene was the best man at her brother Richard’s wedding. Born in Los Angeles, Eugene Merle Shoemaker had graduated from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena at the age of 19. He later earned a master’s degree and joined the United States Geological Survey.

The bride-to-be was Carolyn’s best friend. Before the wedding, all four started hanging out and having fun.

“I was growing to like Gene more and more as time passed. He always seemed so willing to do anything, and he seemed to enjoy everything that I seemed to enjoy. So I thought, ‘Well, we sure have a lot in common.’”

After her brother’s wedding, Carolyn exchanged letters with Gene for a year. Then Gene went back to his job at the USGS in Grand Junction, Colorado, and later to Princeton to work on his Ph.D.

“I was just thinking I might never see him again. So while we had been writing letters back and forth, I stopped writing, and he noticed right away and he wrote me a letter and said, ‘Please keep on writing.’ So I did.”

Eventually, Gene suggested that he and Carolyn go camping on the Colorado Plateau.

“I couldn’t possibly make such a trip without a chaperone, so that was going to be Mother. He had already spoken to her, and Mother loved going camping, and so we did make that trip after school was out.”

The trip went so well that Gene proposed to Carolyn after the first night. Well, he sort of proposed.

“He said something to the effect of, ‘What do you think it would be like to be married to me?’ And I thought, ‘Is this a proposal?’ I said I thought it would be fine. So we went for a few days without saying much about it, and Mother kept saying, ‘Did he propose or not?’ Finally, she asked him, and ‘yes,’ he had proposed, and so we started planning the wedding.”

Carolyn and Gene married on Aug. 18, 1951 – exactly a year after her brother’s wedding. The ceremony took place in Chico, California, Carolyn’s hometown. But the newlyweds were soon back on the Colorado Plateau, continuing Gene’s geological fieldwork. Rather than pitch tents, they slept under the stars. While Gene perfected his craft as a rock hound, Carolyn taught seventh grade. The couple also had three children: Christine, Patrick, and Linda. Carolyn raised the kids while Gene worked and traveled.

Gene’s ‘Impossible Dream’

Gene was an enthusiastic geologist, but he confided to Carolyn that he also had another dream. Ever since he was a boy, he had wanted to go to the Moon. He had been told it was an impossible fantasy, but he didn’t give up.

In 1956 he even tried to interest the USGS in making a geological map of the Moon, but his work was sidelined because the agency’s Cold War priority was to find plutonium to power atomic weapons. (In April 2020 USGS did release the first-ever comprehensive geologic map of the Moon).

Instead of working on a map of the Moon, Gene was assigned to study craters that formed after small nuclear test explosions under Yucca Flat in Nevada, about 80 miles northwest of Las Vegas. The craters were caused by more than 900 nuclear tests conducted by the U.S. government.

Gene’s studies of craters eventually led the Shoemakers to Meteor Crater (also known as Barringer Meteorite Crater) in northern Arizona.

“We got there just at dusk when the light was changing and beginning to fade,” Carolyn said. “We didn’t have any money left after buying the gas, so we didn’t go around to get to admissions. We went up the side of Meteor Crater and peered over the rim, and Gene was entranced.”

At the time of the Shoemakers’ visit, the crater was thought by many to be a dead volcano. But this visit led Gene to think that both Meteor Crater and the lunar craters were made by asteroid impacts.

Gene was awarded a master’s degree in 1954, and in 1960, he received his doctorate from Princeton – with a thesis on Meteor Crater. Gene helped provide the first conclusive evidence that Meteor Crater was indeed an impact site.

On May 25, 1961, Pres. John F. Kennedy announced that the United States would send humans to the Moon. Gene learned he couldn’t become an astronaut due to a health condition – like Pres. Kennedy, Gene had Addison’s disease. He did play an important role in exploring the Moon, though. He helped with NASA’s Ranger missions, and he helped train the Apollo astronauts to do field geology. And when the USGS Center of Astrogeology was founded in Flagstaff in 1965, Gene was appointed its chief scientist.

Gene’s research on impact craters eventually changed the way scientists looked at craters on Earth and the Moon. It also sparked his curiosity about the asteroids and comets that formed these craters, especially those that might collide with Earth.

And that led to Carolyn’s new career.

A New Direction for Carolyn

In 1980, Carolyn, now 51, was ready for a new direction. Her children were grown. She wanted something new to focus on. At the time, Gene was working as a geology professor at Caltech. He also was working on a plan to search for asteroids and comets using the 18-inch (0.46-m) Schmidt telescope at the Palomar Observatory.

Carolyn asked him for ideas.

“I said, ‘Gene, do you have any idea of something I could do that would interest me as much as geology interests you?’ Meaning 48 hours a day. He said, ‘Well, I have this little project up at Palomar.’”

Gene brought home a stereo microscope along with some films – among them, hopefully, discovery images of new comets and asteroids.

“He said, ‘Let’s try this out, and see if you’d like it.’ He and I both had a lot of fun doing that, and he realized that I could see things very well. So that became my job, to look at things on the stereo microscope. I really enjoyed it. You know, it’s kind of fun to go along looking at something and then have an asteroid or a comet pop up above the surface, and realize that that was something that was new and something that was important that you were looking for.”

When Gene suggested she join him to make observations at the telescope, Carolyn was hesitant at first. She wasn’t sure she could stay up all night. But it wasn’t long, though, before the couple was spending their evenings together again under the stars.

“I made a number of trips with Gene, just to discover things on the 18-inch, and he and I had a good time together doing that. And then he went over to the 48-inch to work with Eleanor Helin on the same sort of thing and left me at the 18-inch. It was sort of like a second honeymoon, but when he went off, I found myself singing a song, ‘Now I can do it my way.’”

In 1982 Gene and Carolyn launched the Palomar Asteroid and Comet Survey (PACS, 1982-1994). Within 10 years, the Shoemakers were leaders in asteroid and comet discoveries.

“I found a number of comets, but there was one that was more interesting than all the others put together,” Carolyn said.

Bad Film and a Broken Comet

Carolyn, Gene, amateur astronomer David Levy, and Philippe Bendjoya (an astronomer visiting from France) were at Palomar in March of 1993. The weather had been bad, but when you were signed up to go to a telescope at Palomar you went, Carolyn said, even if the weather wasn’t cooperating. Here are her remembrances of those nights at Palomar that led up to the discovery of a history-making comet:

“When we went, we took some film that had been in a storage box beside the table where I kept the stereo microscope. We took that film, and it was important to use that because we would hyper the film to speed up the emulsion. That meant that we cut out the little round circles of film, six-inch circles, and then we would put it in an oven and bake it. By so doing, we could speed up the emulsion, and instead of having to take exposures that were an hour-long, we could take 10-minute exposures. That was great. It meant that we could do a whole lot more in an observing run.

So the first night, we discovered that the film was not so good because someone had opened the box and exposed all the film, and then closed the lid and not said anything to me.

Gene looked at the film in the box, and by digging down into the middle of the pile, he could find enough film that we could take some images that night. They weren’t very great. The edges had been exposed but not the middle, so that was what we took. Then the second night, we were all set to take some exposures, and we discovered that clouds were beginning to come over.

We would look at the sky and the clouds and say, ‘You think we can take any?’ ‘No.’ David Levy would say, ‘Why don’t we try some of that film that was not good yesterday. It won’t cost us anything, and we might get something at least.’ And so that night, he and Gene rushed to the telescope and set up, and before the clouds came entirely, they managed to take a few films.

Later, the fourth night or fifth night of the observing run, it was raining outside. Gene was reading Time magazine. David was looking at his computer, and Philippe was out in the car sleeping. I was looking at the films.

My process was to start at the top and move slowly across the film, and then down and back and so on across the film. All of a sudden I realized there was something strange. I backed up, and there was this strange-looking object, and I didn’t know what it was. I thought, ‘Well, it’s probably some effect from Jupiter,’ which was on the film, and which often had rays coming out from it and other effects on the film.

I moved the film around, and I looked at the position of Jupiter and the position of my film and thought, ‘No, Jupiter didn’t have anything to do with this.’ And it was strange because it almost looked like a line of fuzzy comets. So I said, ‘You know, I don’t know what I have here. Would you take a look?’ And Gene came rushing over. He was just amazed. He couldn’t figure it out either, and David came and looked, and Philippe came in from the car and looked. We all thought, ‘What can it be?’

We reported the position to the Minor Planet Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts. And Gene remarked, “I wonder if that’s a broken comet.”

David knew that Jim Scotti at the telescope in Tucson might be observing that night, and maybe he could take a look at this strange object for us. He was using a telescope that was quite a bit bigger than our 18-inch, so he could see this strange thing more clearly. And he called Scotti, and Scotti said, ‘Well, I’ve got an awful lot to do, but I’ll take a look at your object if I have time.’ In short order, he called back and he said, ‘Boy, have you guys got a comet.’”

Carolyn and Gene Shoemaker and David Levy had discovered the comet that would bear their names in a photograph taken on March 18, 1993, with the 0.4-meter Schmidt telescope at Mt. Palomar. And Gene Shoemaker’s instinct was correct. The comet was broken into a row of fragments, each with its own tail. The comet fragments were lined up like a string of pearls.

‘Oh, I'm Going to Lose My Comet’

The Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory led the team that tracked the comet fragments, and the team determined the comet was in orbit around Jupiter. But that wasn’t all.

“The second month that we were observing,” Carolyn said, “David [Levy] got a message from the Minor Planet Center saying that this comet was going to hit Jupiter.

“After that, the scientific world sort of exploded, but it really exploded in the little 18-inch dome. David was so excited and pleased, and he was jumping up and down, and Gene was in the darkroom at that moment trying to get the film ready for that night. He heard the excitement, and came out and rushed over to David’s computer and took a look at the message and was so excited. This was the comet he always hoped to see.

I was dismayed. I thought, ‘Oh, I’m going to lose my comet. I’ve never lost a comet before. I have a whole bunch of comets that I can see every now and then, and I would never see this one again.’ But after a while, I came around and I was excited too.”

Gene later gave Carolyn a gift to replace the lost comet. “Gene gave me a string of pearls in commemoration of what we had found, and they were beautiful,” she said.

A Final Adventure

In the early 1980s, the Shoemakers realized Australia has a lot of old craters like Meteor Crater in Arizona. They started traveling around the Australian Outback together for three months each year. It was the type of adventure that had always bonded them together: immersed in nature, sleeping out under the stars.

“All of the roads were known as tracks in the Outback, and they were pretty rough,” Carolyn said. “Some of them were in areas where there had been fires going across the landscape. When eucalyptus burns, it leaves a little spike of itself sticking up. Nothing like driving across that spike. Generally speaking, whenever we drove cross-country or even on the tracks, we would have at least one flat tire a day. Gene was a pro at fixing flat tires. Twenty-three flat tires was our record.”

On July 18, 1997, three years after the Shoemaker-Levy 9 comet hit Jupiter, the Shoemakers were on their 12th Australian trip. They were driving toward the Goat Paddock Crater – a 3-mile-wide crater created millions of years ago when an asteroid hit Earth.

“We had been driving for two days, and we were approaching the border of Western Australia and South Australia. We had not seen another vehicle for a day and a half, since we had left the Great Northern Highway and started on this track. It was a big wide dirt track, and we were driving as all Aussies do in the Outback. Everyone drives down the middle of the road. That was the smoothest place. We were going around that curve in the middle of the road, and when we glanced up, there was a Land Rover right in front of us, and we impacted.”

Gene died in the crash. He was 69 years old.

“When the impact occurred, I was thrown down on the controls down on the bottom,” Carolyn recalled. “In the other vehicle, the people were hurt a little bit but not very much. They came and checked, but quickly went back to their own vehicle and we waited. I had been wondering as I lay there in the bottom of the car why Gene didn’t come around and open the door and get me out because that’s what he would ordinarily have done. But of course, he couldn’t.”

Carolyn said that after a while another vehicle from a gold mining camp came and called Australia’s Royal Flying Doctor Service, which provides emergency services in remote areas.

“They came, and also brought the jaws of life and pried the door open and got me out and into the airplane – and then told me that Gene was dead,” she said.

Carolyn was hospitalized for several days after the accident. “I had broken ribs. I had sprains here and there. I was really in pretty bad shape. I couldn’t walk for a while.”

The Man on the Moon

Gene was cremated, and some of his ashes were scattered at Meteor Crater. But some of his remaining ashes completed the journey he had always dreamed of – they were taken to the Moon on NASA’s Lunar Prospector spacecraft.

“While I was still in the hospital, I had a call from Carolyn Porco. She had been one of Gene’s students at Caltech, and she said that Lunar Prospector, a mission to the Moon, was going to be leaving shortly, and we could possibly put a capsule of Gene’s ashes on it and he could go to the Moon. I was thrilled by that.”

The whole family went to see the Lunar Prospector launch on Jan. 7, 1998.

“We were pretty excited. Gene had always wished he could go to the Moon, and now he was going to go. We saw the liftoff, which was both happy and sad. We feel like his dream really did come true.”

After orbiting the Moon for a year, the Lunar Prospector carrying Gene Shoemaker’s cremains made a planned crash-landing into a lunar crater in 1999. This made Gene the only person to be buried on the Moon. That crater in the Moon’s south pole was renamed “Shoemaker” in his honor.

“I look up at the Moon and I think Gene’s up there. I wave at it in my mind and I say, ‘Hi, Gene, how are you doing? Are you finding a lot of interesting rocks?’ And he would say, ‘This is great stuff. Wish you were here!’ We hold a little conversation.”

In 1999, she wrote an autobiographical essay for the “Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences” and reflected on her life with Gene and her future without him.

“Without the human relationships we cherish, knowledge would count for naught; both are to be nourished. Henceforth, I’ll continue my scientific exploration, knowing that I must not neglect the other side of living,” she wrote.

A Meteoric Career

Though Carolyn Shoemaker didn’t start her astronomy career until she was in her 50s, she more than made up for any lost time.

She became a visiting scientist in the Astrogeology Branch of the U.S. Geological Survey – the program her husband founded.

In 1989, she became a Research Professor of Astronomy at Northern Arizona University, and in 1993 joined the staff of the Lowell Observatory. From 1981 to 1985, she served as a research assistant at the California Institute of Technology.

Carolyn – who had earlier received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Chico State College in California – received an honorary doctorate of science from Northern Arizona University in 1990.

With her husband, she received the Rittenhouse Medal in 1988 and became a Cloos Scholar at Johns Hopkins University in 1990. Carolyn was awarded NASA’s Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal in 1996.