Renu Malhotra

Professor of Planetary Sciences - University of Arizona

Contents

- Where are you from?

- Describe the first time you made a personal connection with outer space.

- How did you end up working in the space program?

- What is a Professor of Planetary Sciences at the University of Arizona?

- Tell us about a favorite moment so far in your career.

- Who inspired you?

- What advice would you give to someone who wants to take the same career path as you?

- What do you do for fun?

- If you were talking to a student interested in science and math or engineering, what advice would you give them?

- Read More

- Where are they from?

This profile has been adapted in part from an original interview by Kathryn (Kat) Gardner-Vandy and Susan Niebur for the “Women in Planetary Science” website. To read the full interview, click here.

Where are you from?

India. I was born in New Delhi. I grew up mostly in Hyderabad, which is on the Deccan Plateau and near the geometrical center of the Indian sub-continent. It is in a semi-arid climate zone, surprisingly similar to the high desert region of the southwestern U.S., which is where I live now.

If you recognize an anomaly in your area, dig into it. More often than not, you’ll find something interesting.- Renu Malhotra

Describe the first time you made a personal connection with outer space.

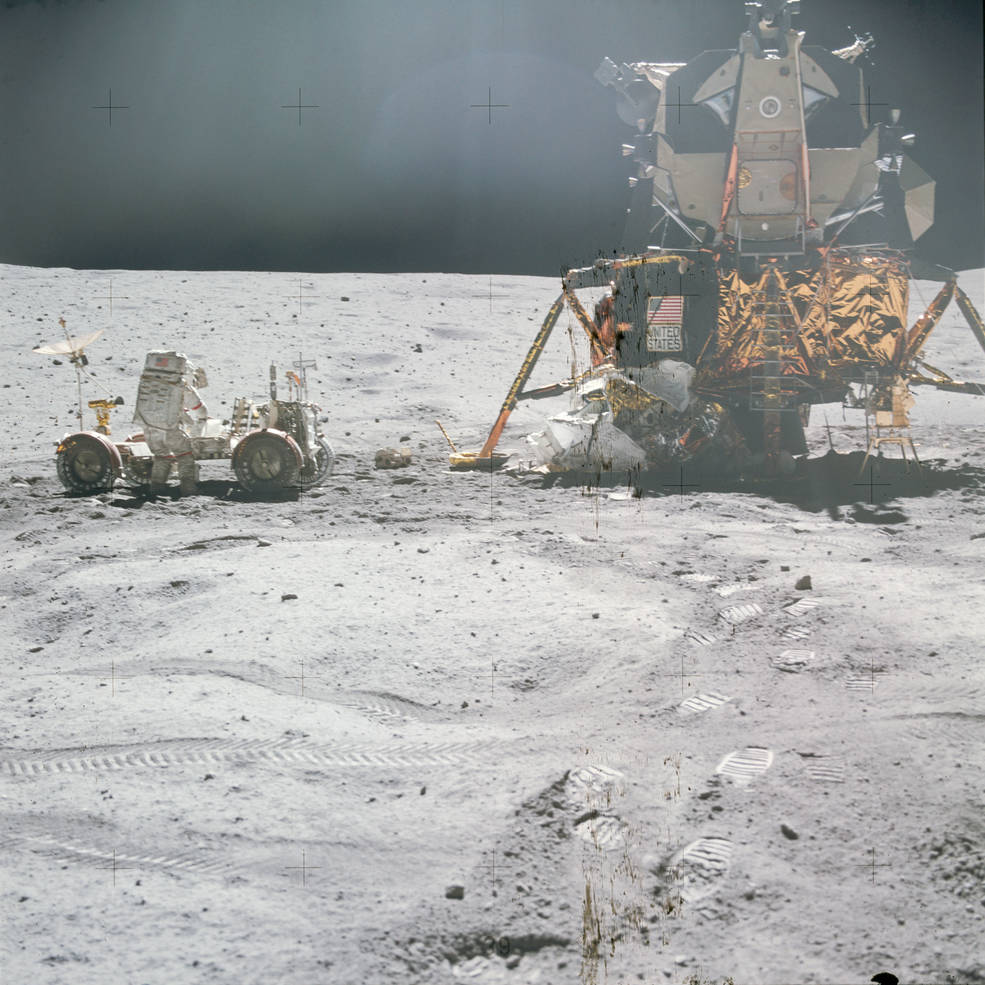

I remember that it was during the summer of 1969 when I was eight-years old. I was jumping rope outside, and a neighbor’s radio was blaring loudly in the background. Suddenly, the pop music was interrupted with a news bulletin about the Apollo 11 lunar landing. I remember freezing with my rope, abandoning my playmates and then climbing up to the neighbor’s window in order to hear all the details of the news. I held my breath throughout the entire news bulletin, but inside my head I couldn’t stop saying, “Wow! Wow!”

How did you end up working in the space program?

By high school I had decided that I wanted to devote my life to “understanding how nature works.” I had an affinity for math and I studied physics in college (in India). I then went to Cornell University for graduate studies in physics. I had long wanted to come to the United States due to its reputation for higher education, but also because American culture embraces the values of freedom. India was not a free country (from my point of view). So, the idea of being free in the freest country on Earth was a big dream for me.

My first summer at Cornell, I worked on a project in non-linear dynamics and chaos theory. I became very interested in this field. However my advisor Mitchell Feigenbaum, left Cornell shortly thereafter. I needed a new advisor, so, I contacted several professors in the astronomy department who were studying planetary dynamics (which is the preeminent non-linear dynamical system!), and found an advisor there: Stanley Dermott.

With Stan as an advisor, I worked on the Uranian satellites (a rather current topic at the time in the wake of the Voyager 2 flyby of Uranus in 1986). The first problem Stan suggested to me was the anomalous motion of one of Uranus’s moons named Miranda. Within a few weeks, I came up with an answer of what was going on with Miranda’s orbit. I hardly knew anything about orbits at that time — for me it was all about knowing the equations and getting a feel for where the anomaly was coming from. I received some attention from wise people in planetary science by solving that problem.

I found that I loved working with equations of orbital mechanics. This was a whole new world, and I felt like I belonged in it.

What is a Professor of Planetary Sciences at the University of Arizona?

My job is a mix of teaching, research and service.

Teaching includes formal lecture classes, as well as informal advising of undergraduate and graduate students. My research is how I carry on my curiosity-driven calling, “understanding how nature works,” in the particular discipline of planetary dynamics. I often work with graduate students in some of my research projects. This helps me to pass on my knowledge and to train the next generation of scientists. Such students earn a Ph.D. degree when they complete a significant research project.

The “service” part of my job description involves several different types of activities at several different levels.

Service to my university and department is in the form of participation in the self-governance of the university. For example, I serve on the Ph.D. examination committees for my own, as well as other departments and on committees that make faculty-hiring and promotion decisions. Currently, I am also serving as director of an inter-disciplinary program in theoretical astrophysics.

Service to my scientific community consists of providing evaluations of scientists for prospective employment or for promotions, reviewing scientific papers and research proposals, evaluating academic programs for accreditation agencies, organizing scientific conferences, and providing advice to science-policy makers.

Service to the public consists of writing about my science for non-specialists, giving presentations of my research to public audiences, organizing science activities for K-12 students and teachers, and answering queries from journalists.

Tell us about a favorite moment so far in your career.

One fine day in the spring of 2004, after many months of attempts, I finally persuaded a senior colleague in my department with my theoretical interpretation of his data on impact craters that he had collected over a 35-year career. The joy of successfully communicating my idea to him was incomparable. We later wrote a paper together on an important part of the planets’ meteoritic bombardment history.

Who inspired you?

My father inspired in me an abiding curiosity about the physical world and how things work. Mitchell Feigenbaum sparked my interest in non-linear dynamics. Stanley Dermott and Peter Goldreich inspired my interest in planetary dynamics.

What advice would you give to someone who wants to take the same career path as you?

Work hard and acquire command of the technical parts of your scientific subfield so it does not hamper your exploration of the edges of knowledge. Then pick important problems — there are interesting and important problems everywhere. You just have to be open to them. If you recognize an anomaly in your area, dig into it. More often than not, you’ll find something interesting. For me, one such problem was Pluto. That was a peculiar planet, now called a dwarf planet. It didn’t fit in. I don’t know if anyone recognized it back then as a major issue, but it bothered me — it felt like grit in my mind. It led me to a pivotal discovery for solar system science — the idea that the planets migrated from their birthplaces.

What do you do for fun?

I enjoy vegetable gardening in a community garden in my neighborhood. I also like to play Sudoku and watch movies.

If you were talking to a student interested in science and math or engineering, what advice would you give them?

Find an area that appeals to you. Find good mentors and a peer group in which you can learn together. Have fun with the subject.

Read More

Post on Renu on the Women in Planetary Science Website

Renu’s University of Arizona Faculty Page

Renu is Featured in “Astro Confidential” in “Astronomy Magazine” (June 2011)

National Geographic (July 2013) Feature with Renu

Where are they from?

Planetary science is a global profession.