July 8, 2014: Fruit flies are bug eyed and spindly, they love rotten bananas, and, following orders from their pin-sized brains, they can lay hundreds of eggs every day.

We have a lot in common.

Genetically speaking, people and fruit flies are surprisingly alike, explains biologist Sharmila Bhattacharya of NASA's Ames Research Center. "About 77% of known human disease genes have a recognizable match in the genetic code of fruit flies, and 50% of fly protein sequences have mammalian analogues."

A new ScienceCast video considers the fruit fly as astronaut:

Drosophila melanogaster

could help NASA travel deeper into space than ever before.

That's why fruit flies, known to scientists as Drosophila melanogaster, are commonplace in genetic research labs. They can be good substitutes for people. They reproduce quickly, so that many generations can be studied in a short time, and their genome has been completely mapped. Drosophila is being used as a genetic model for several human diseases including Parkinson's and Huntington's.

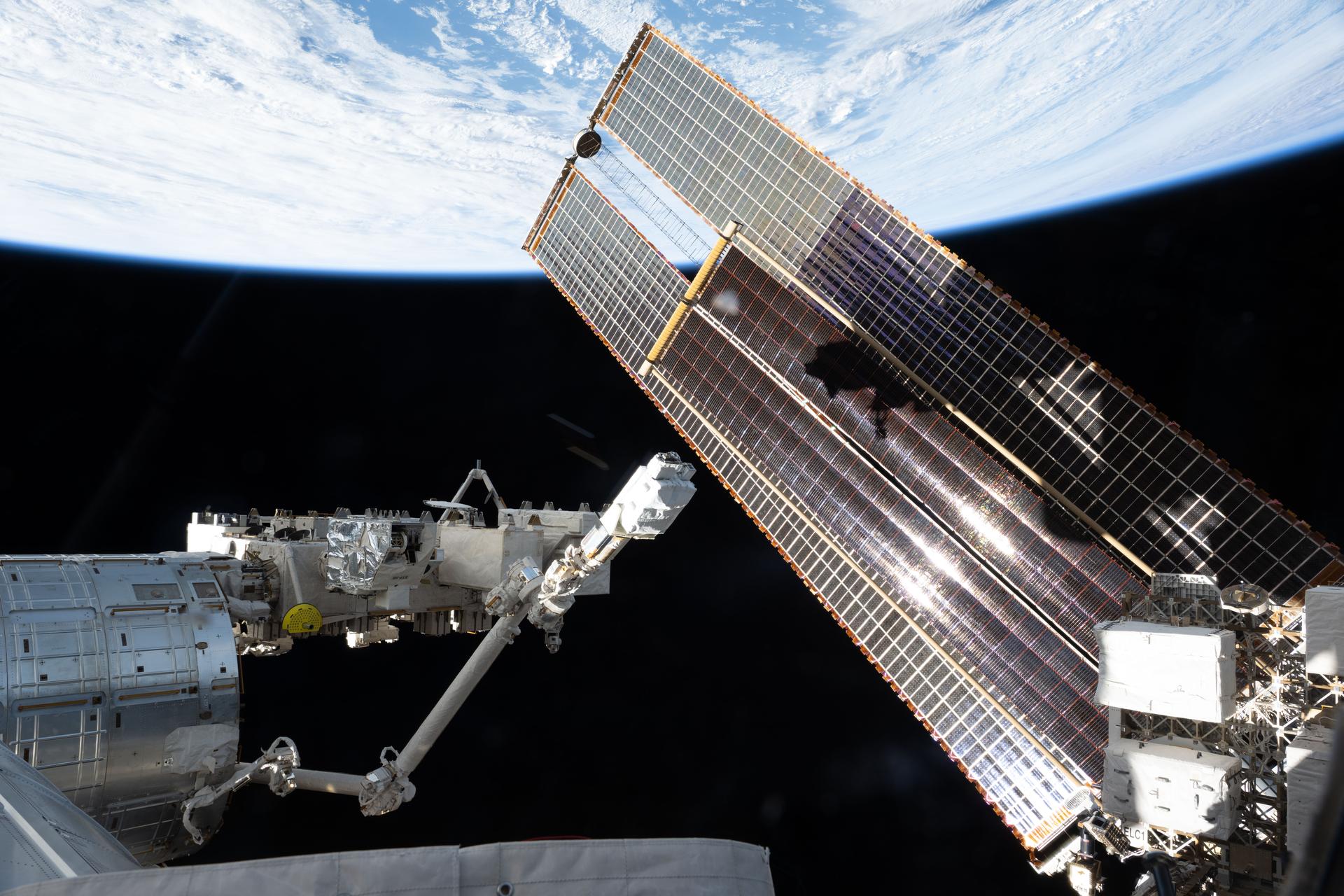

They're about to become genetic models for astronauts. "We are sending fruit flies to the International Space Station," says Bhattacharya. "They will orbit Earth alongside astronauts, helping us explore the effects of long-term space flight on human beings."

The flies will be living in a habitat developed at Ames called the "Fruit Fly Lab." Inside, they will lead the hurried lives of fruit flies--living, dying, reproducing, and experiencing the same space radiation and microgravity as their human counterparts. Cameras will record the behavior and appearance of these miniature astronauts; and at intervals some of them will be frozen and returned to Earth for analysis.

This research was recommended by the National Research Council itself. In a recent Decadal Survey, the council noted that "model systems offer increasingly valuable insights into basic biology." And they called for "an organized effort to identify common changes in gene expression [among] key model systems in space."

"The Fruit Fly Lab will allow us to look into a variety of questions such as the effect of space flight on aging, cardiovascular fitness, sleep, stress and much more," she says.

Visit the Fruit Fly Lab

Bhattacharya's personal interest is the immune system. It has long been known that astronauts' ability to resist disease is weakened in space. Turns out, the same thing happens to fruit flies. "We sent Drosophila to Earth orbit onboard Space Shuttle Discovery in 2006, and they all experienced a decrement in immune function," says Bhattacharya.

The shuttle flight was relatively brief, only 13 days, but astronauts traveling to Mars and other distant places will be in space much longer. A fruit fly habitat permanently installed on the ISS allows researchers to conduct studies directly relevant to such long-duration space flight.

Immune system studies of human astronauts can be tricky because every astronaut has his or her own idiosyncratic genetic code. "What's nice about the flies we send up is that they are all genetically identical," notes Bhattacharya. "We can do much better science with such a population."

Flies onboard the space station will also have their own "carnival ride." A 1-g centrifuge will subject Drosophila to the equivalent of Earth-gravity, allowing researchers for the first time to unravel the competing influences of radiation and gravity. "This is cutting-edge research," she says, clearly enthusiastic about this new device.

The Fruit Fly Lab is scheduled to launch in late summer 2014 onboard a Space-X rocket.

Maybe they should pack some bananas, too. Rotten, if you please.

Credits:

Author: R. Molina | Production editor: Dr. Tony Phillips | Credit: Science@NASA