Algae are complicated. The little plants can be both good and bad.

Single-celled algae called phytoplankton are a main source of food for fish and other aquatic life, and account for half of the photosynthetic activity on Earth—that’s good.

But certain varieties such as some cyanobacteria produce toxins that can harm humans, fish, and other animals. Under certain conditions, algae populations can grow explosively -- a spectacle known as an algal bloom, which can cover hundreds of square kilometers. For example, in August 2014, a cyanobacteria outbreak in Lake Erie prompted Toledo, Ohio, officials to ban the use of drinking water supplied to more than 400,000 residents.

With support from NASA, the EPA has developed an app to track algae that can threaten fresh water supplies.

In the United States alone, freshwater degradation from "bad" algae costs the economy about $64 million a year.

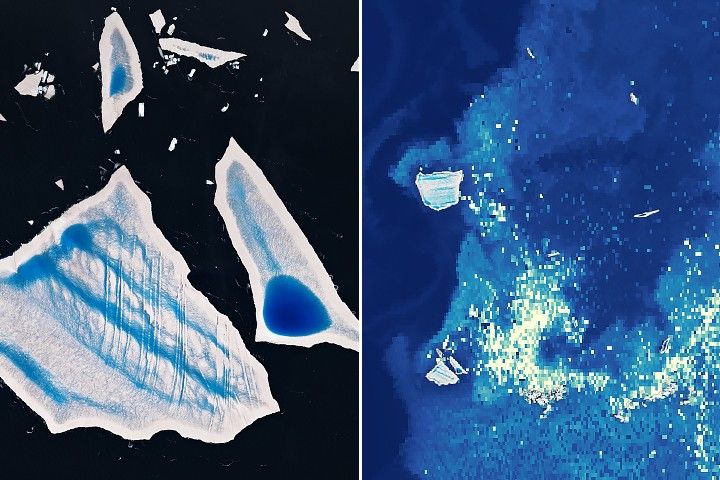

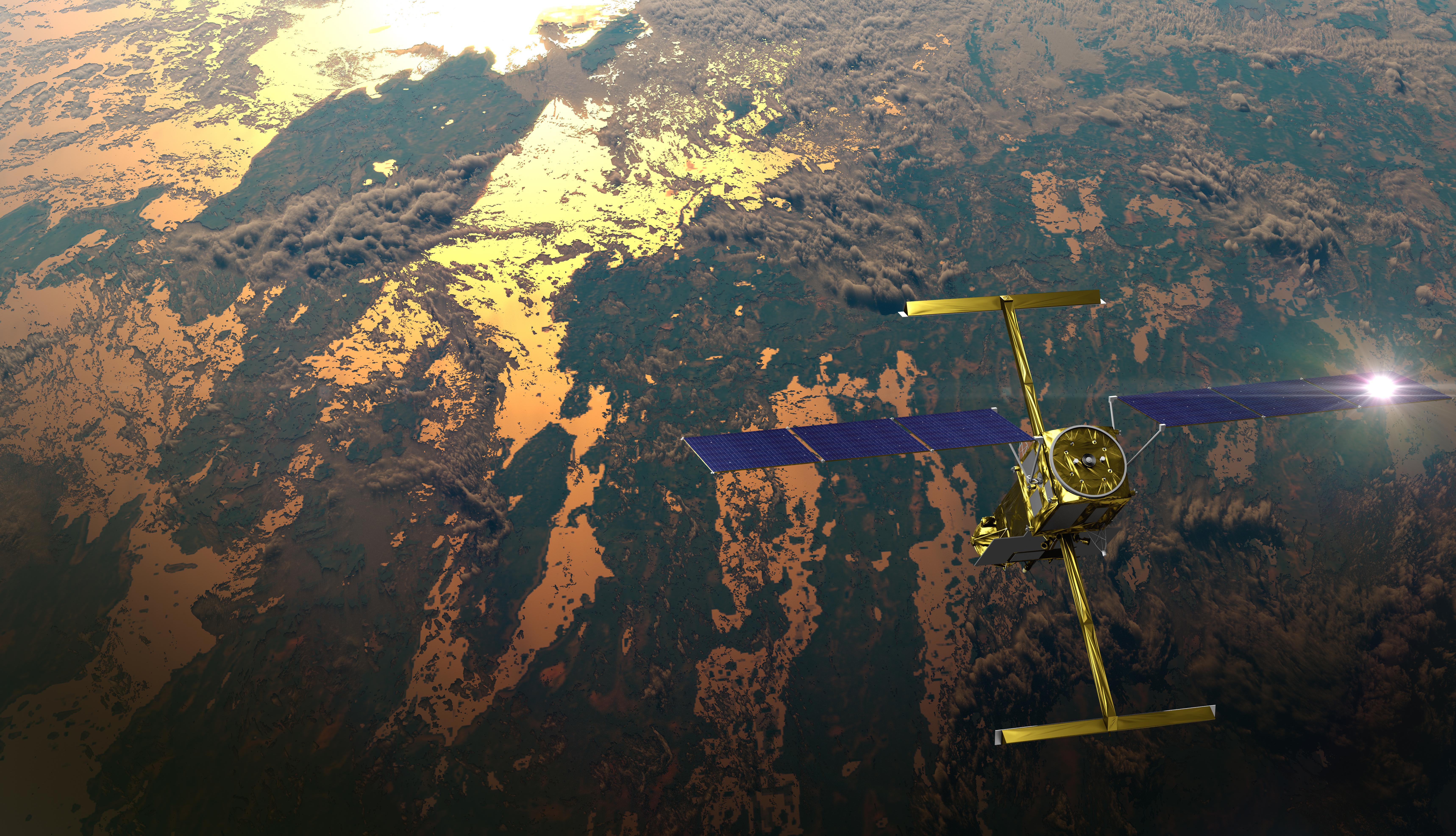

NASA, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and U.S. Geological Survey are doing something about it. NASA has long used Earth observing satellites to locate algal bloom outbreaks in the ocean. But now, this unique satellite data will be routinely produced in a form that helps US water quality managers monitor our freshwater. Water quality managers will soon, with a peek at their cell phones, have an answer to "how's the water?"

The four agencies are working on a joint project, sponsored by NASA, to transform satellite data into an indicator of cyanobacteria outbreaks in our freshwater supply. The data will be integrated into an EPA Android smart phone application so environmental officials can see – at a glance – the condition of a specific water body.

"With our app, you can view water quality on the scale of the US, and zoom in to get near-real-time data for a local lake," explains the EPA's Blake Schaeffer, Principal Investigator for the project. "When we start pushing this data to smartphone apps, we will have achieved something that's never been done – provide water quality satellite data like weather data. People will be able to check the amount of 'algae bloom' like they would check the temperature."

Here’s how it works:

A harmful species of cyanobacteria emits chlorophyll and fluorescent light at various points in their life cycles. Landsat and NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) can detect these "ocean color" signals, which reveal the location and abundance of cyanobacteria. The project team will collect this data for freshwater bodies and convert it into a form accessible through web portals and the EPA mobile app. In addition to MODIS, they'll draw data from the European Space Agency's Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-3.

With early warning about a developing bloom, officials at water treatment plants will be better able to determine when, where, and how much to treat the water to keep consumers safe. That means unnecessary -- and expensive -- overtreatment may be avoided. The data will also help park managers alert swimmers, boaters, and other recreational users to hazardous conditions.

Says NASA Administrator Charles Bolden: “We’re excited to be putting NASA’s expertise in space and scientific exploration to work protecting public health and safety."

The project will also help scientists understand why "bad" algae outbreaks occur. By comparing the color data with landcover change data, they’ll learn more about environmental factors that spur algal growth. The result: better forecasts of bloom events. So we’ll know when an algae bloom is safe or harmful.