High above Earth’s poles, intense electrical currents called electrojets flow through the upper atmosphere when auroras glow in the sky. These auroral electrojets push about a million amps of electrical charge around the poles every second. They can create some of the largest magnetic disturbances on the ground, and rapid changes in the currents can lead to effects such as power outages. In March, NASA plans to launch its EZIE (Electrojet Zeeman Imaging Explorer) mission to learn more about these powerful currents, in the hopes of ultimately mitigating the effects of such space weather for humans on Earth.

Results from EZIE will help NASA better understand the dynamics of the Earth-Sun connection and help improve predictions of hazardous space weather that can harm astronauts, interfere with satellites, and trigger power outages.

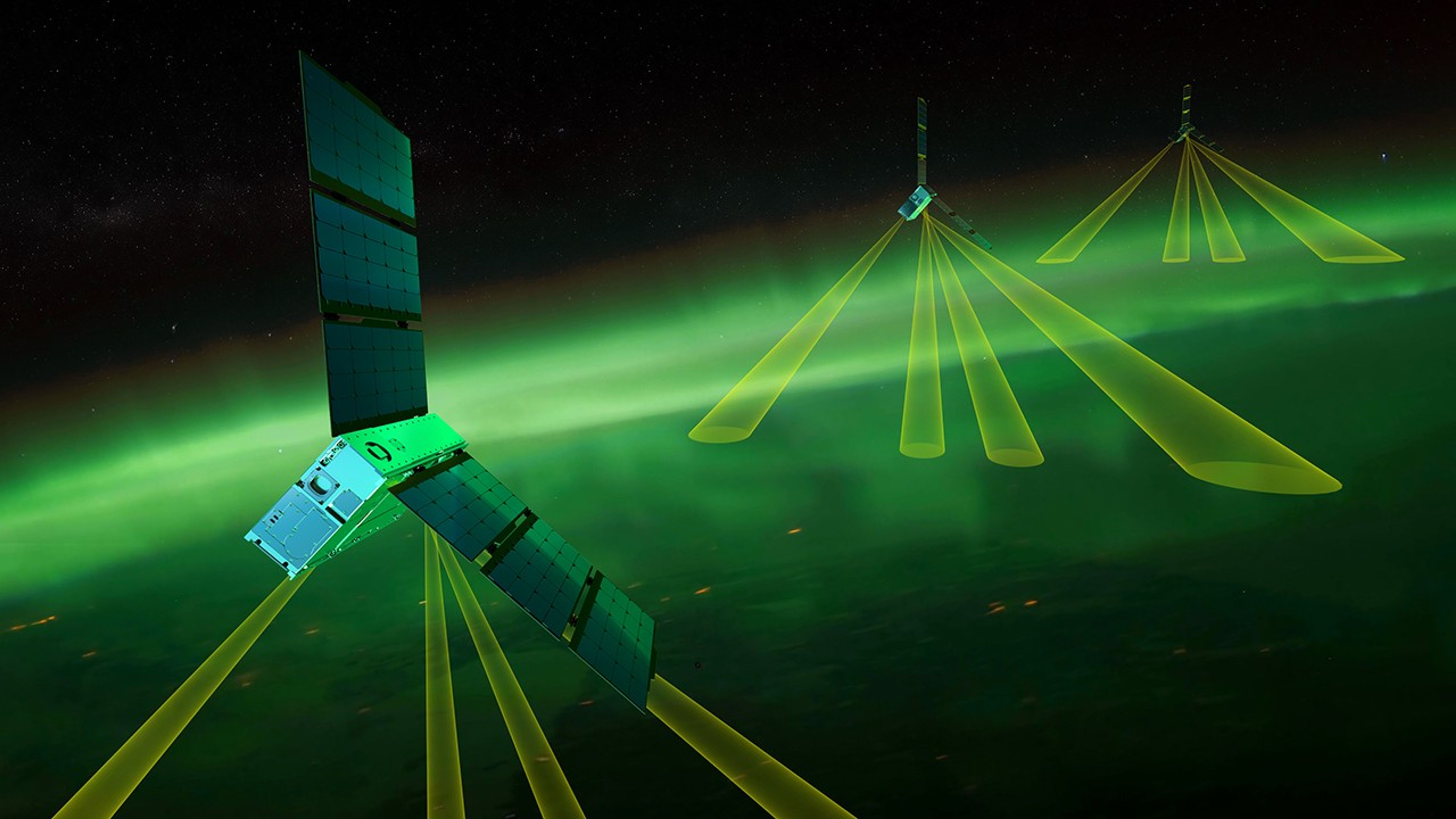

The EZIE mission includes three CubeSats, each about the size of a carry-on suitcase. These small satellites will fly in a pearls-on-a-string formation, following each other as they orbit Earth from pole to pole about 350 miles (550 kilometers) overhead. The spacecraft will look down toward the electrojets, which flow about 60 miles (100 kilometers) above the ground in an electrified layer of Earth’s atmosphere called the ionosphere.

During every orbit, each EZIE spacecraft will map the electrojets to uncover their structure and evolution. The spacecraft will fly over the same region 2 to 10 minutes apart from one another, revealing how the electrojets change.

Previous ground-based experiments and spacecraft have observed auroral electrojets, which are a small part of a vast electric circuit that extends 100,000 miles (160,000 kilometers) from Earth to space. But for decades, scientists have debated what the overall system looks like and how it evolves. The mission team expects EZIE to resolve that debate.

“What EZIE does is unique,” said Larry Kepko, EZIE mission scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “EZIE is the first mission dedicated exclusively to studying the electrojets, and it does so with a completely new measurement technique.”

EZIE is the first mission dedicated exclusively to studying the electrojets.

Larry Kepko

EZIE mission scientist, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

This technique involves looking at microwave emission from oxygen molecules about 10 miles (16 kilometers) below the electrojets. Normally, oxygen molecules emit microwaves at a frequency of 118 Gigahertz. However, the electrojets create a magnetic field that can split apart that 118 Gigahertz emission line in a process called Zeeman splitting. The stronger the magnetic field, the farther apart the line is split.

Each of the three EZIE spacecraft will carry an instrument called the Microwave Electrojet Magnetogram to observe the Zeeman effect and measure the strength and direction of the electrojets’ magnetic fields. Built by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California, each of these instruments will use four antennas pointed at different angles to survey the magnetic fields along four different tracks as EZIE orbits.

The technology used in the Microwave Electrojet Magnetograms was originally developed to study Earth’s atmosphere and weather systems. Engineers at JPL had reduced the size of the radio detectors so they could fit on small satellites, including NASA’s TEMPEST-D and CubeRRT missions, and improved the components that separate light into specific wavelengths.

The electrojets flow through a region that is difficult to study directly, as it’s too high for scientific balloons to reach but too low for satellites to dwell.

“The utilization of the Zeeman technique to remotely map current-induced magnetic fields is really a game-changing approach to get these measurements at an altitude that is notoriously difficult to measure,” said Sam Yee, EZIE’s principal investigator at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland.

The mission is also including citizen scientists to enhance its research, distributing dozens of EZIE-Mag magnetometer kits to students in the U.S. and volunteers around the world to compare EZIE’s observations to those from Earth. “EZIE scientists will be collecting magnetic field data from above, and the students will be collecting magnetic field data from the ground,” said Nelli Mosavi-Hoyer, EZIE project manager at APL.

EZIE scientists will be collecting magnetic field data from above, and the students will be collecting magnetic field data from the ground.

Nelli Mosavi-Hoyer

EZIE project manager, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory

The EZIE spacecraft will launch aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California as part of the Transporter-13 rideshare mission with SpaceX via launch integrator Maverick Space Systems.

The mission will launch during what’s known as solar maximum — a phase during the 11-year solar cycle when the Sun’s activity is stronger and more frequent. This is an advantage for EZIE’s science.

“It’s better to launch during solar max,” Kepko said. “The electrojets respond directly to solar activity.”

The EZIE mission will also work alongside other NASA heliophysics missions, including PUNCH (Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere), launching in late February to study how material in the Sun’s outer atmosphere becomes the solar wind.

According to Yee, EZIE’s CubeSat mission not only allows scientists to address compelling questions that have not been able to answer for decades but also demonstrates that great science can be achieved cost-effectively.

“We’re leveraging the new capability of CubeSats,” Kepko added. “This is a mission that couldn’t have flown a decade ago. It’s pushing the envelope of what is possible, all on a small satellite. It’s exciting to think about what we will discover.”

The EZIE mission is funded by the Heliophysics Division within NASA’s Science Mission Directorate and is managed by the Explorers Program Office at NASA Goddard. APL leads the mission for NASA. Blue Canyon Technologies in Boulder, Colorado, built the CubeSats.

by Vanessa Thomas

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Header Image:

An artist's concept shows the three EZIE satellites orbiting Earth.

Credits: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Steve Gribben