3 min read

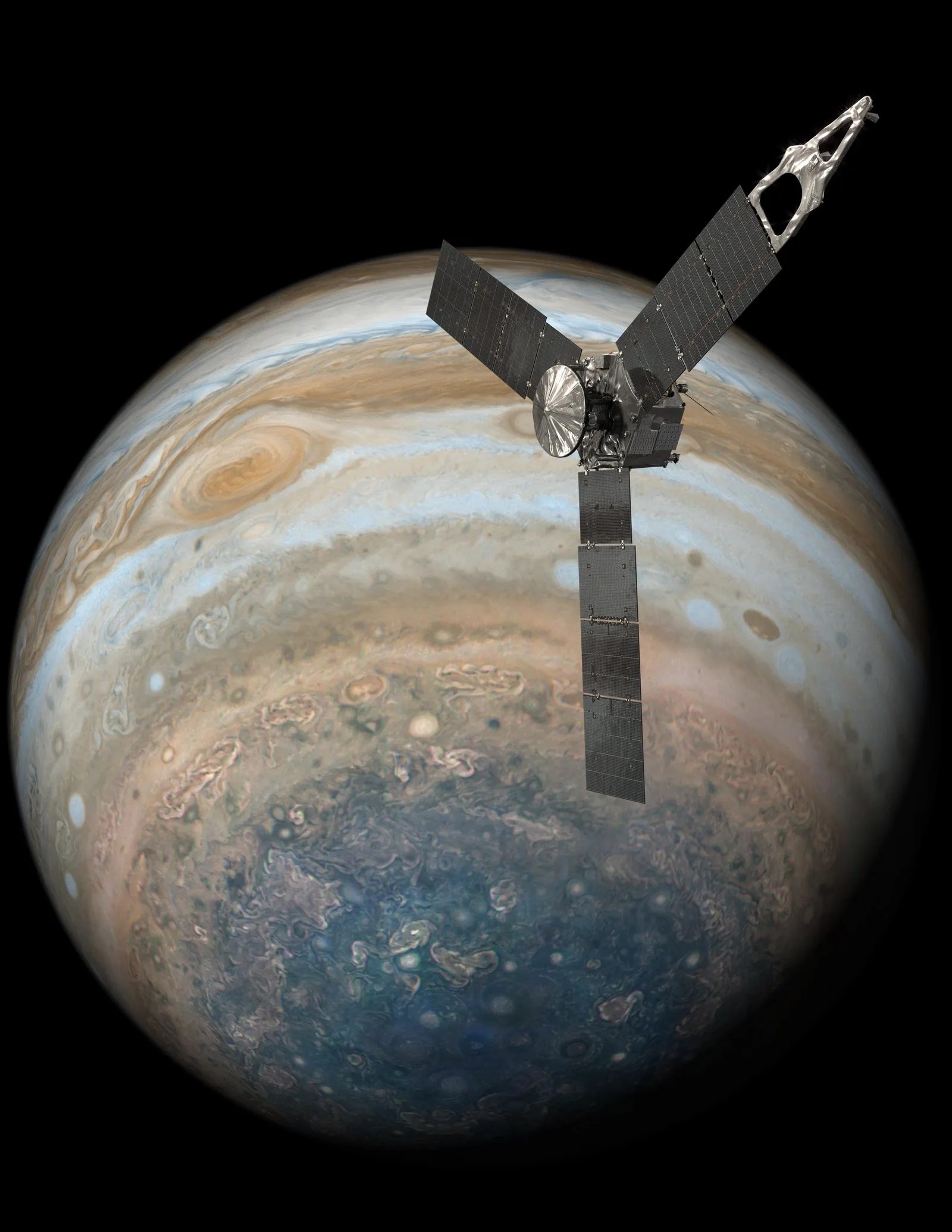

Over 980 million miles or about 1.6 billion kilometers from home, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft hurtles through the starry expanse of space. From its vantage point orbiting Saturn, Earth is nothing more than a miniscule pinprick of light not unlike the stars framing the gorgeous ringed planet.

Cassini has been orbiting Saturn since 2004, and it has made dozens of flybys of Saturn’s intriguing moons. Its next close encounter with Enceladus on October 28, 2015 promises potentially exciting results.

NASA's Cassini Spacecraft is about to make a daring plunge through one of the plumes emerging from Saturn's moon Enceladus.

Enceladus boasts an icy, ostensibly barren landscape riddled with deep canyons, dubbed “tiger stripes.” Underneath its icy exterior churns a global ocean, heated in part by tidal forces from Saturn and another moon, Dione, with seafloor vents expelling water at at least 194 degrees Fahrenheit. Plumes of water vapor and icy particles jettison from its surface in geyser-like spouts, hinting that there is much more to this snowy moonscape than meets the eye.

Cassini will be soaring through the jets located at the moon’s south pole, only 30 miles above the surface.

"Although the October 28th flyby won’t be the closest we’ve ever been to Enceladus, it is the closest flyby over the south pole and through the plume,” says Linda Spilker, the Cassini Project Scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “We’ll be exploring in situ a region of the plume that Cassini has never sampled before. This is very exciting for me!"

So what causes these plumes, and why are they so important? Enceladus’ vast, subterranean oceans may be fizzy and full of gas. When the gas and icy particles rise to the surface, they are expelled in plumes shooting from the “tiger stripes.” In the words of Linda Spilker, the process is similar to “shaking up a bottle of soda; the gas has nowhere to go but up and out.”

However, the plumes are more than just gas and water: samples show that they also contain many of the building blocks essential to Earth-like life. This lends itself to the exciting possibility that organisms similar to those that thrive in our own deep oceans near volcanic vents exuding carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide might exist on Eceladus. Although it is still too early to know exactly how complex potential Enceladus’ lifeforms could be, scientists speculate that at the very least microbial life is a real possibility.

In the future, a different spacecraft may journey across the solar system to visit icy Enceladus. This spacecraft, unlike Cassini, could be designed to land on Enceladus’ surface, near one of its “tiger stripes.” Such a lander would be able to take samples more directly, bypassing the plume altogether.

“Ideally, it could take samples from the edge of one of the tiger stripes,” speculates Spilker. This would ensure that any microbes being expelled from Enceladus’ interior would be more plentiful and easier to collect.

Until then, flybys are the best we can do. And the next one should be very good indeed. Tune in on Oct. 28th!