2 min read

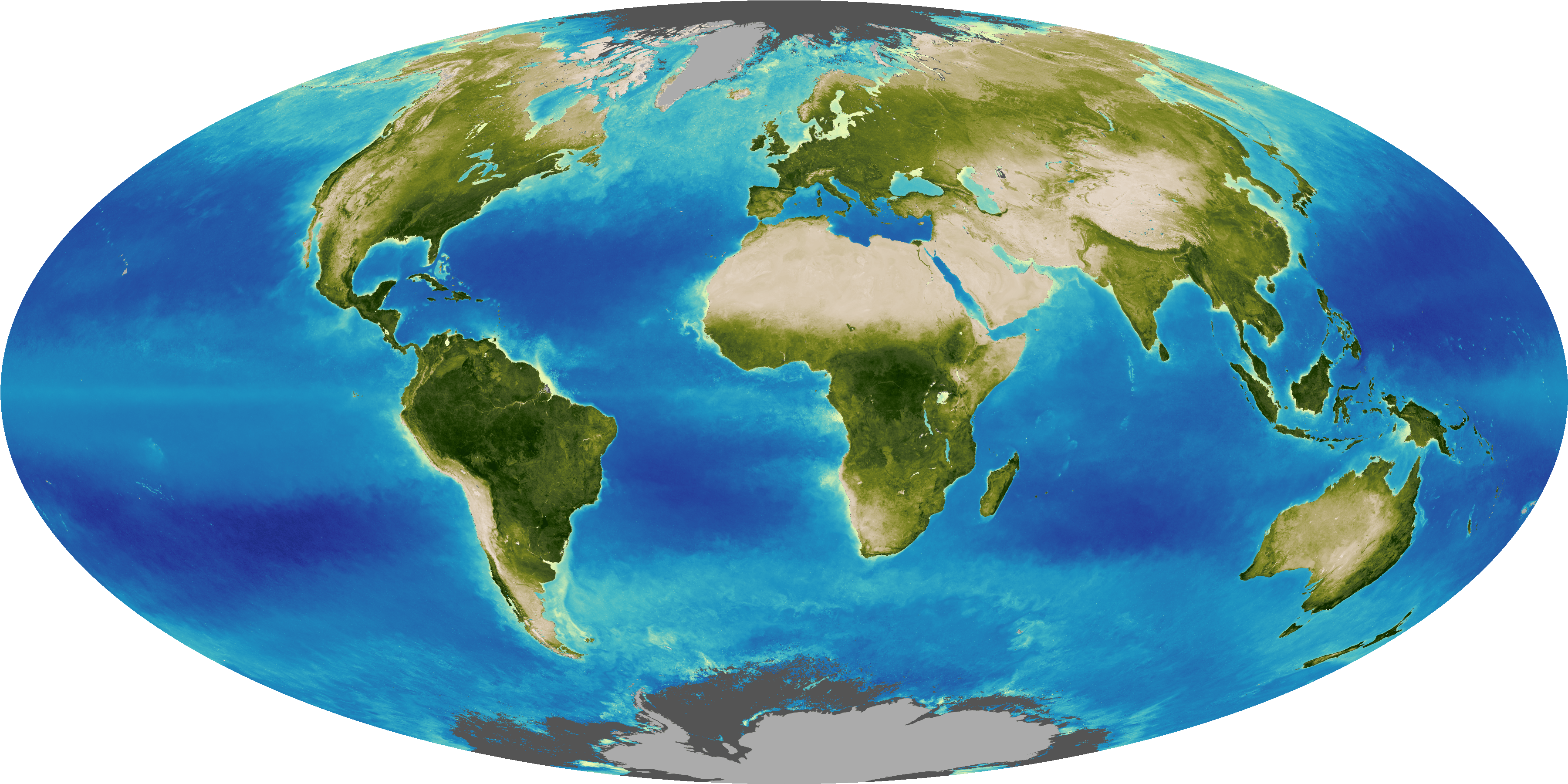

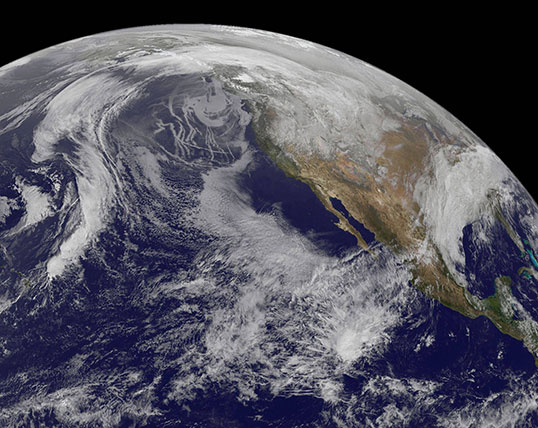

Of all the factors that influence Earth’s changing climate, the effect that tiny particles in Earth’s atmosphere called aerosols have on clouds is the least well understood. Aerosols scatter and absorb incoming sunlight and affect the formation and properties of clouds. Among all cloud types, low-level clouds over the ocean, which cover about one-third of the ocean’s surface, have the biggest impact on the albedo, or reflectivity, of Earth’s surface, reflecting solar energy back to space and cooling our planet.

Now a new, comprehensive global analysis of satellite data led by Yi-Chun Chen, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, and a joint team of researchers from JPL and the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, has quantified how changes in aerosol levels affect these warm clouds over the ocean. The findings appeared Aug. 3 in the advance online version of the journal Nature Geoscience.

Changes in aerosol levels have two main effects — they alter the amount of clouds in the atmosphere and change their properties. Water vapor condenses on aerosol particles into cloud droplets or cloud ice particles, so higher levels of aerosols mean more clouds. With regard to cloud properties, increased aerosol levels can either increase or decrease the amount of liquid water in clouds, depending on whether the clouds are raining or not, the stability of the atmosphere and humidity levels in the upper troposphere. The team analyzed 7.3 million individual data points from multiple satellites in the international constellation of Earth observing satellites known as the Afternoon Constellation, or A-Train, from August 2006 to April 2011 to provide the first real estimate of both effects.

The researchers found each effect to be of similar magnitude — that is, changing the amount of the clouds and changing their internal properties are both equally important in their contribution to cooling our planet. Moreover, they found that the total impact from the influence of aerosols on this type of cloud is almost double that estimated in the latest report of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

“These results offer unique guidance on how warm cloud processes should be incorporated in climate models with changing aerosol levels,” said John Seinfeld, the Louis E. Nohl professor and professor of chemical engineering at Caltech.

The study is funded by NASA and the Office of Naval Research.