Pluto's moon Charon was discovered on June 22, 1978. It's the dwarf planet’s largest, and first known moon. Get to know Pluto’s beautiful, fascinating companion.

1. A Happy Accident

Astronomers James Christy and Robert Harrington weren’t even looking for satellites of Pluto when they discovered Charon in June 1978 at the U.S. Naval Observatory Flagstaff Station in Arizona – only about six miles from where Pluto was discovered at Lowell Observatory. Instead, they were trying to refine Pluto's orbit around the Sun when sharp-eyed Christy noticed images of Pluto were strangely elongated – a blob seemed to move around Pluto. The direction of elongation cycled back and forth over 6.39 days – the same as Pluto's rotation period. Searching through their archives of Pluto images taken years before, Christy then found more cases where Pluto appeared elongated. Additional images confirmed he had discovered the first known moon of Pluto.

2. Forever and Always

Christy proposed the name Charon after the mythological ferryman who carried souls across the river Acheron, one of the five mythical rivers that surrounded Pluto's underworld. But Christy also chose it for a more personal reason: The first four letters matched the name of his wife, Charlene. (Cue the collective sigh.)

3. Big Little Moon

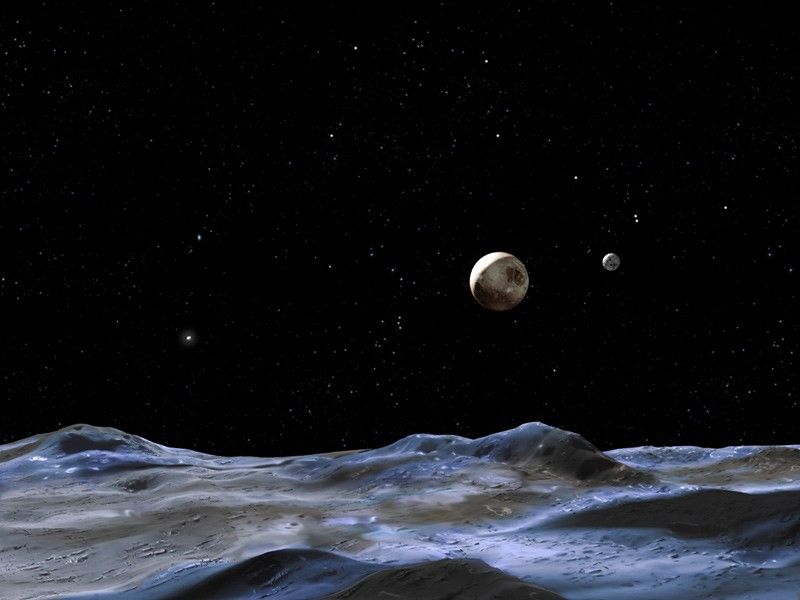

Charon—the largest of Pluto’s five moons and approximately the size of Texas—is almost half the size of Pluto itself. The little moon is so big that Pluto and Charon are sometimes referred to as a double dwarf planet system. The distance between them is 12,200 miles (19,640 kilometers).

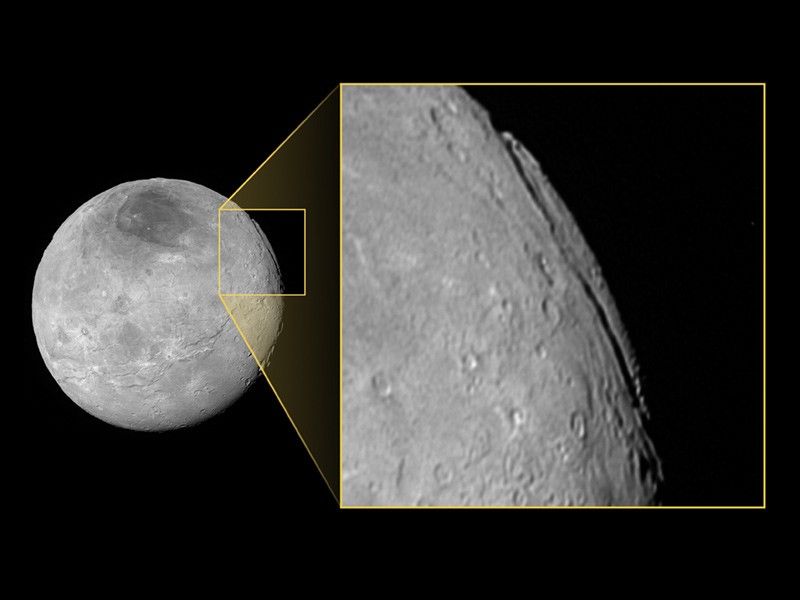

4. A Colorful and Violent History

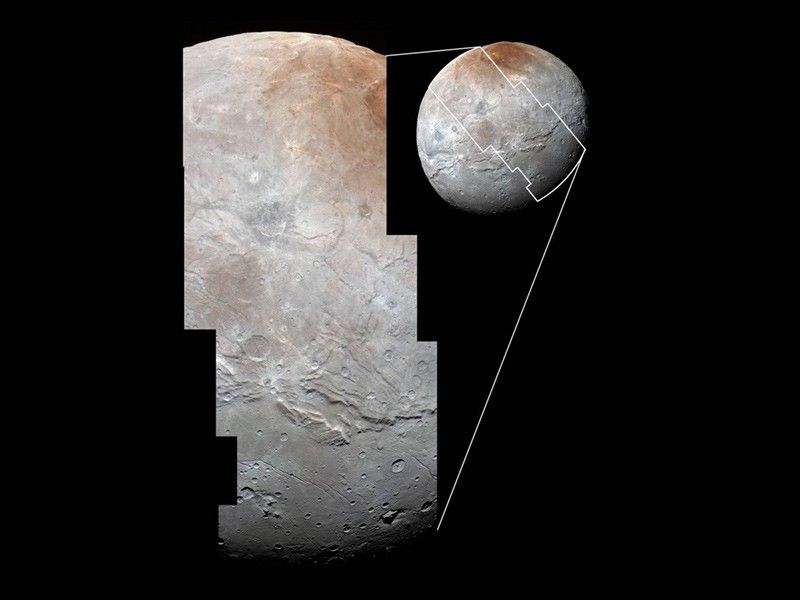

Many scientists on the New Horizons mission expected Charon to be a monotonous, crater-battered world. Instead, they found a landscape covered with mountains, canyons, landslides, surface-color variations and more. High-resolution images of the Pluto-facing hemisphere of Charon, taken by New Horizons as the spacecraft sped through the Pluto system on July 14, 2015, and transmitted to Earth on Sept. 21, reveal details of a belt of fractures and canyons just north of the moon’s equator.

5. A Grander Canyon

This great canyon system stretches more than 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) across the entire face of Charon and likely around onto Charon’s far side. It's four times as long as the Grand Canyon on Earth, and twice as deep in places, these faults and canyons indicate a titanic geological upheaval in Charon’s past.

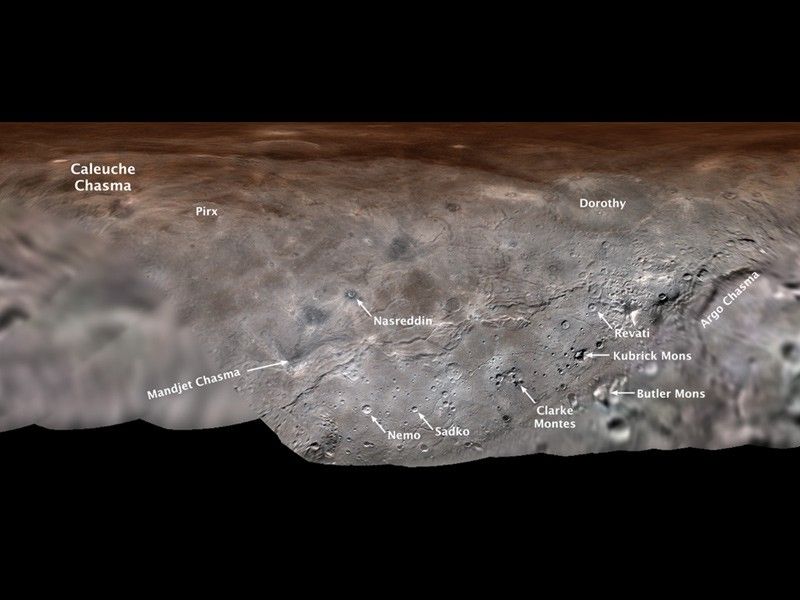

6. Officially Official

In April 2018, The International Astronomical Union – the internationally recognized authority for naming celestial bodies and their surface features – approved a dozen names for Charon’s features proposed by NASA's New Horizons mission team. Many of the names focus on the literature and mythology of exploration.

7. Fly Over Charon

This flyover video of Charon was created thanks to images from NASA's New Horizons spacecraft. The “flight” starts with the informally named Mordor (dark) region near Charon’s north pole. Then the camera moves south to a vast chasm, descending to just 40 miles (60 kilometers) above the surface to fly through the canyon system.

8. Strikingly Different Worlds

This composite of enhanced color images of Pluto (lower right) and Charon (upper left), was taken by New Horizons as it passed through the Pluto system on July 14, 2015. This image highlights the striking differences between Pluto and Charon. The color and brightness of both Pluto and Charon have been processed identically to allow direct comparison of their surface properties, and to highlight the similarity between Charon’s polar red terrain and Pluto’s equatorial red terrain.

9. Quality Facetime

Charon neither rises nor sets, but hovers over the same spot on Pluto's surface, and the same side of Charon always faces Pluto – a phenomenon called mutual tidal locking.

10. Shine on, Charon

Bathed in “Plutoshine,” this image from New Horizons shows the night side of Charon against a star field lit by faint, reflected light from Pluto itself on July 15, 2015.