Meteors & Meteorites Facts

What’s that flash of light streaking across the sky? We call the objects that creates this brilliant effect by different names, depending on where it is.

Quick Facts

Meteoroids

Meteoroids are space rocks that range in size from dust grains to small asteroids. This term only applies when these rocks while they are still in space.

Most meteoroids are pieces of other, larger bodies that have been broken or blasted off. Some come from comets, others from asteroids, and some even come from the Moon and other planets. Some meteoroids are rocky, while others are metallic, or combinations of rock and metal.

Meteors

When meteoroids enter Earth’s atmosphere, or that of another planet, at high speed and burn up, they’re called meteors. This is also when we refer to them as “shooting stars.” Sometimes meteors can even appear brighter than Venus – that’s when we call them “fireballs.” Scientists estimate that about 48.5 tons (44,000 kilograms) of meteoritic material falls on Earth each day.

Meteor Showers

Several meteors per hour can usually be seen on any clear night. When there are lots more meteors, you’re watching a meteor shower. Some meteor showers occur annually or at regular intervals as the Earth passes through the trail of dusty debris left by a comet (and, in a few cases, asteroids).

Meteor showers are usually named after a star or constellation that is close to where the meteors appear to originate in the sky. Perhaps the most famous are the Perseids, which peak around August 12 every year. Every Perseid meteor is a tiny piece of the comet Swift-Tuttle, which swings by the Sun every 135 years. Other notable meteor showers include the Leonids, associated with comet Tempel-Tuttle; the Aquarids and Orionids, linked to comet Halley, and the Taurids, associated with comet Encke. Most of this comet debris is between the size of a grain of sand and a pea and burns up in the atmosphere before reaching the ground. Sometimes, meteor dust is captured by high-altitude aircraft and analyzed in NASA laboratories.

When to Watch Meteor Showers

| Major Meteor Streams | 2025 Peak Viewing Night (may vary by a few days)* | Rate Per Hour** | Parent Body (Asteroid or Comet) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrantids | Jan. 2-3, 2025 | 120 | (196256) 2003 EH1 |

| Lyrids | April 21-22, 2025 | 18 | Comet C/1861 G1 |

| Eta Aquarids | May 3-4, 2025 | 50 | Comet 1P/Halley |

| Southern Delta Aquariids | July 29-30, 2025 | 25 | Comet 96P/Machholz (not confirmed) |

| Perseids | Aug. 12-13, 2025 | 100 | Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle |

| Orionids | Oct. 22-23, 2025 | 20 | Comet 1P/Halley |

| Leonids | Nov. 16-17, 2025 | 15 | Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle |

| Geminids | Dec. 12-13, 2025 | 150 | (3200) Phaethon |

| Ursids | Dec. 21-22, 2025 | 10 | Comet 8P/Tuttle |

* For observers in the northern hemisphere.

** Estimated rate per hour in under perfect conditions, based on activity in recent years.

Meteorites

When a meteoroid survives its trip through the atmosphere and hits the ground, it’s called a meteorite. Meteorites typically range between the size of a pebble and a fist.

Most space rocks smaller than a football field will break apart in Earth’s atmosphere. Traveling at tens of thousands of miles per hour, the object disintegrates as pressure exceeds the strength of the object, resulting a bright flare. Less than 5% of the original object usually makes it down to the ground.

Don’t expect to find meteorites after a meteor shower. Most meteor showers come from comets, whose material is quite fragile. Small comet fragments generally won’t survive entry into our atmosphere. In theory, the Taurids and Geminids could send meteorites down to our surface every once in a while, but no remnants have been traced to them definitively.

It can be difficult to tell the difference between a meteorite and an Earth rock, but there are some special places where they’re much easier to identify: deserts. In sandy deserts with large, open regions of sand and few rocks, dark meteorites stand out. Similarly, meteorites can be much easier to spot in cold, icy deserts, such as the frozen plains of Antarctica.

Why Do We Care About Meteorites?

Meteorites that fall to Earth represent some of the original, diverse materials that formed planets billions of years ago. By studying meteorites we can learn more about our solar system’s history. This includes learning the age and composition of different planetary building blocks, the temperatures achieved at the surfaces and interiors of asteroids, and the degree to which materials were shocked by impacts in the past.

What Do Meteorites Look Like?

Meteorites may resemble Earth rocks, but they usually have a burned exterior that can appear shiny. This “fusion crust” forms as the meteorite’s outer surface melts while passing through the atmosphere.

There are three major types of meteorites: the “irons,” the “stonys,” and the “stony-irons.” Although the majority of meteorites that fall to Earth are stony, most of the meteorites discovered long after they fall are irons. Irons are heavier and easier to distinguish from Earth rocks than stony meteorites.

Where Do Meteorites Come From?

Most meteorites found on Earth come from shattered asteroids, although some come from Mars or the Moon. In theory, small pieces of Mercury or Venus could have also reached Earth, but none have been conclusively identified.

Scientists can tell where meteorites originate based on several lines of evidence. They can use photographic observations of meteorite falls to calculate orbits and project their paths back to the asteroid belt. They can also compare compositional properties of meteorites to the different classes of asteroids. And they can study how old the meteorites are – up to 4.6 billion years.

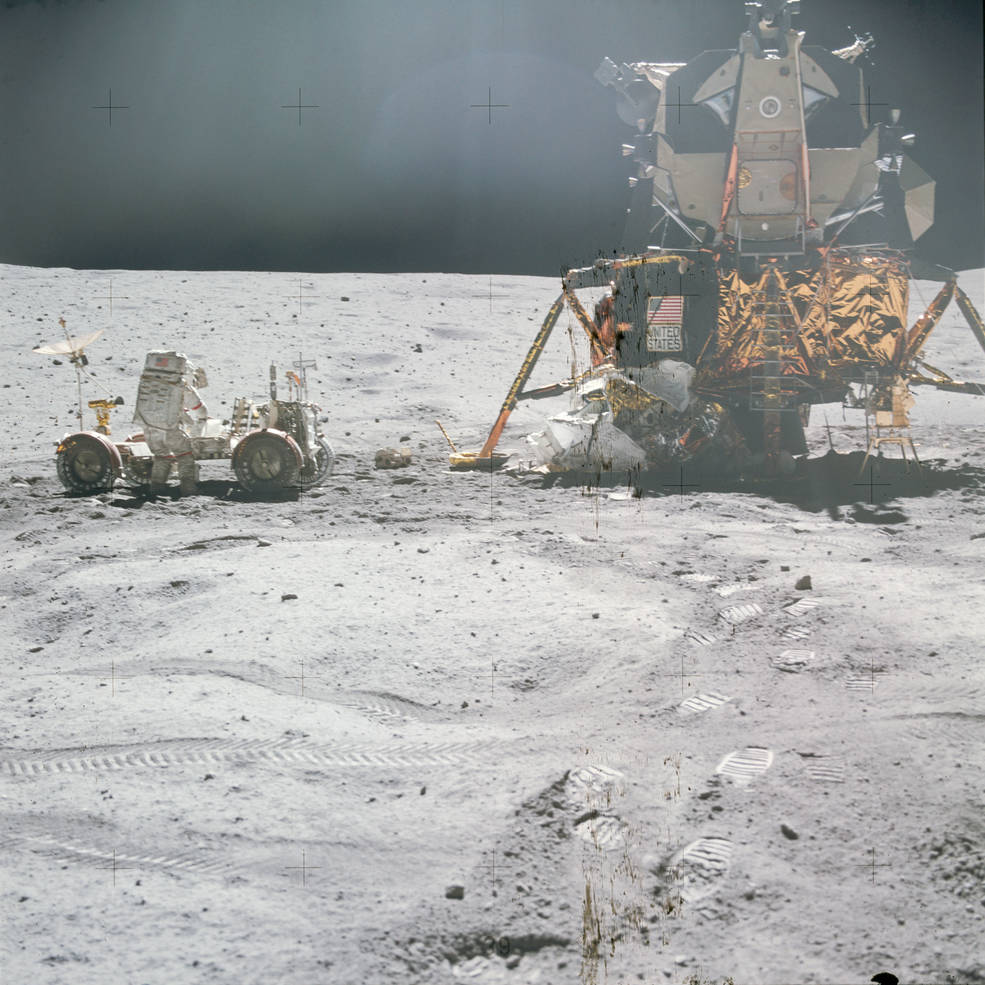

Martian rocks can be traced to the Red Planet because they contain pockets of trapped gas that matches what satellites and rovers have found at Mars. Similarly, if the composition of a meteorite resembles rocks that astronauts brought back from the Moon during the Apollo mission, it is likely to be lunar, too. Thanks to NASA’s Dawn mission, we know that a class of meteorites called “howardite-eucrite-diogenite” (HED) came from asteroid Vesta in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

What Kinds of Meteorites Have Been Found?

More than 50,000 meteorites have been found on Earth.

Of these, 99.8% come from asteroids. The remaining small fraction (0.2%) of meteorites is split roughly equally between meteorites from Mars and the Moon. The over 60 known Martian meteorites were blasted off Mars by meteoroid impacts. All are igneous rocks crystallized from magma. The rocks are very much like Earth rocks with some distinctive compositions that indicate Martian origin.

The nearly 80 lunar meteorites are similar in mineralogy and composition to Apollo mission Moon rocks, but distinct enough to show that they have come from other parts of the Moon. Studies of lunar and Martian meteorites complement studies of Apollo Moon rocks and the robotic exploration of Mars.

Meteorite Impacts in History

Early Earth experienced many large meteor impacts that caused extensive destruction. While most craters left by ancient impacts on Earth have been erased by erosion and other geologic processes, the Moon’s craters are still largely intact and visible. Today, we know of about 190 impact craters on Earth.

A very large asteroid impact 65 million years ago is thought to have contributed to the extinction of about 75% of marine and land animals on Earth at the time, including the dinosaurs. It created the 180-mile-wide (300-kilometer-wide) Chicxulub Crater on the Yucatan Peninsula.

One of the most intact impact craters is the Barringer Meteorite Crater (also called Meteor Crater) in Arizona. It’s about 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) across and was formed by the impact of a piece of iron-nickel metal approximately 164 feet (50 meters) in diameter. It is only 50,000 years old, and it is so well preserved that it has been used to study impact processes. Geologists have studied the crater since the 1890s, but its status as an impact crater wasn’t confirmed until 1960.

Well-documented stories of meteorites causing injuries or deaths are rare. Ann Hodges of Sylacauga, Alabama, was severely bruised by a 8-pound (3.6-kilogram) stony meteorite that crashed through her roof in November 1954. It was the first documented case of a person being injured by an extraterrestrial object in the United States.

The only entry of a large meteoroid into Earth’s atmosphere in modern history with firsthand accounts was the Tunguska event of 1908. This meteor struck a remote part of Siberia in Russia, but didn’t quite make it to the ground. Instead, it exploded in the air a few miles up. The force of the explosion was powerful enough to knock over trees in a region hundreds of miles wide. Scientists think the meteor itself was about 120 feet (37 meters) across and weighed 220 million pounds (100 million kilograms). Locally, hundreds of reindeer were killed, but there was no direct evidence that any person perished in the blast.

In 2013 the world was startled by a brilliant fireball that streaked across the sky above Chelyabinsk, Russia. The house-sized meteoroid entered the atmosphere at over 11 miles (18 kilometers) per second and blew apart 14 miles (23 kilometers) above the ground. The explosion released the energy equivalent of around 440,000 tons of TNT and generated a shock wave that blew out windows over 200 square miles (518 square kilometers) and damaged buildings. More than 1,600 people were injured in the blast, mostly due to broken glass.