5 min read

Two years ago, planetary scientists across the world watched as Europe and the US did something amazing. The Huygens descent module drifted down through the hazy atmosphere of Saturn's moon Titan, beaming its data back to Earth via the Cassini mothership. Today, Huygens's data are still continuing to surprise researchers.

Titan holds a unique place in the Solar System. It is the only moon covered in a significant atmosphere. The atmosphere has long intrigued scientists as it may be similar to that of the early Earth but the deeper mystery was: what lies beneath the haze?

The European Space Agency built the Huygens spacecraft to find out. The probe, carrying scientific investigations involving both sides of the Atlantic, hitched a ride on NASA's Cassini spacecraft. Together Cassini and Huygens make an unprecedented joint space mission - as a major milestone, Huygens parachuted to the surface of Titan on 14 January 2005.

While Cassini keeps flying by this moon of Saturn collecting new amazing data, one can say that the data collected by Huygens's six instruments during its 2.5-hour descent and touch-down have provided the most spectacular view of this world yet and first dramatic change in the way we now think about it.

"When you put all the data together, we get a very rich picture of Titan," says Athéna Coustenis, Observatoire de Paris, France, "The Descent Imager/Spectral Radiometer (DISR) pictures were an enormous surprise. We had expected a much smoother landscape." Instead, they saw a varied landscape of channels that had been formed by some kind of flowing liquid.

"At the landing site we also saw rounded ice pebbles," says Jonathan Lunine, University of Arizona. The Surface Science Package (SSP) provided the final piece in this particular puzzle. The impact it detected when Huygens touched down indicated that the spacecraft had come to rest in compacted gravel. "Put it all together and it is clear that Huygens landed in an outflow wash," says Lunine.

The Gas Chromatograph and Mass Spectrometer (GCMS) instrument confirmed the nature of the liquid that shapes the surface of Titan. It detected methane evaporating from the Huygens landing site. "Methane on Titan plays the role that water plays on Earth," concludes Lunine. But there are still mysteries. It is not yet clear whether the methane falls mostly as a steady drizzle or as an occasional deluge.

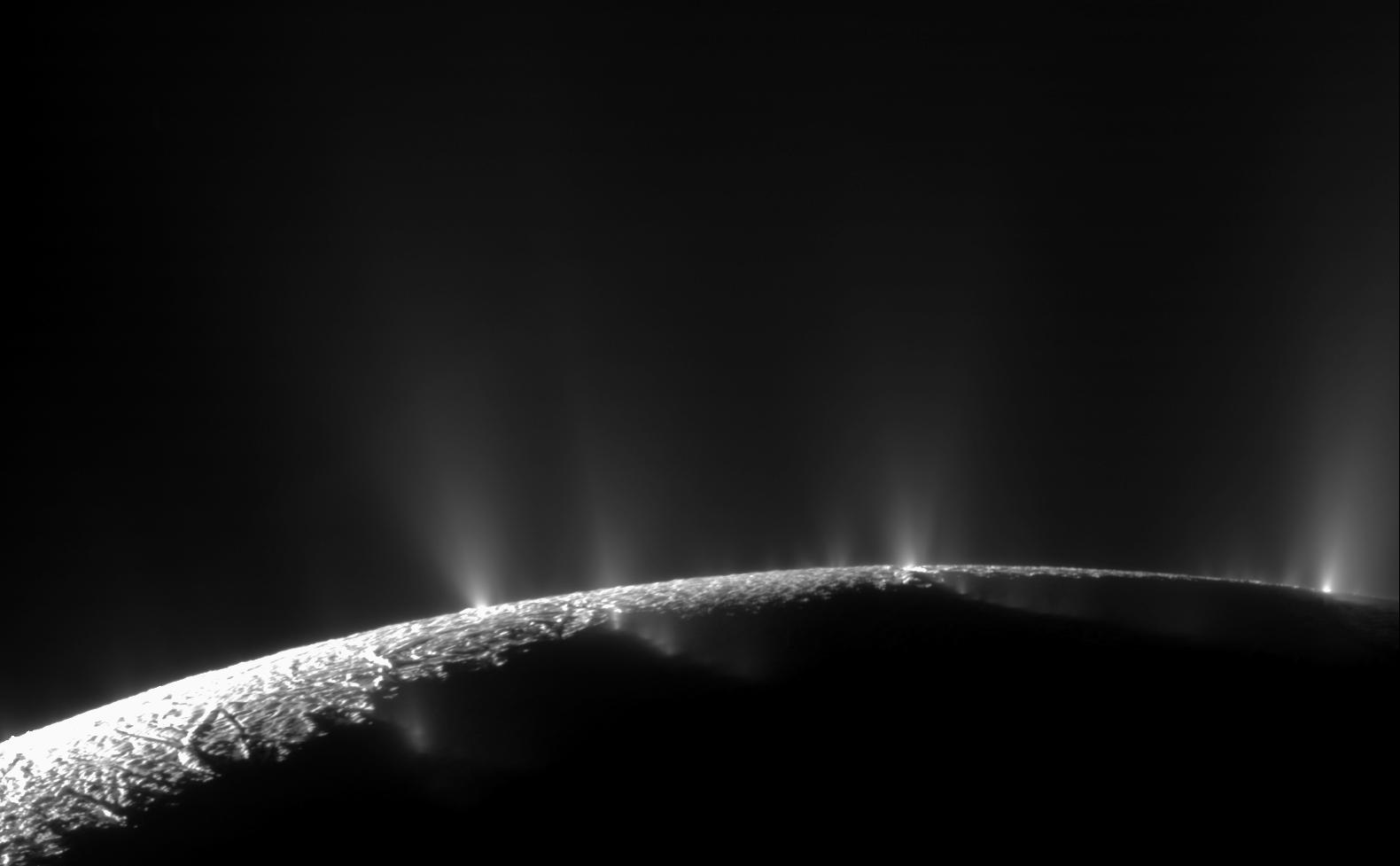

The GCMS also detected two isotopes of argon. Both have important stories to tell. The Ar40 indicates that the interior of Titan is still active. This is unusual in a moon and indicates that perhaps an insulating layer of water ice and methane is buried in the moon itself, close to the surface, trapping the heat inside it. Occasionally, this heat causes the so-called cryo-volcanoes to erupt. Icy 'lava' flows from these cryo-volcanoes have been seen from the orbiting Cassini spacecraft. Because Ar40 is so heavy, it is mostly concentrated towards the base of the atmosphere, so having Huygens on the surface was essential for its detection.

Daniel Gautier, Observatoire de Paris, France, thinks that the other isotope, Ar36, is telling scientists that Titan formed after Saturn, at a time when the primeval gas cloud that became the Solar System had cooled to about 40 °K (-233 °C).

The atmosphere of Titan held surprises too. "Huygens made a fantastic and unexpected discovery about the wind," says Gautier. At an altitude of around 60 kilometres, the wind speed dropped, essentially to zero. Explaining this behaviour presents a challenge for theoreticians who are developing computer models of the moon's atmospheric circulation.

The Huygens Atmosphere Structure Instrument (HASI) provided the temperature of the atmosphere from 1600 kilometres altitude down to the surface. "This has helped put all the other data into context," says Coustenis. Huygens measured the composition profile of the atmosphere to be a mixture of nitrogen, methane and ethane. The methane and ethane provide humidity, as water does in Earth's atmosphere. At the surface of Titan, Huygens measured the temperature to be 94 °K (-179 °C) with a humidity of 45 percent.

Even though the Huygens data set is now two years old, the discoveries have not yet stopped. "There are lots of surprises still to come from this data," says Francesca Ferri, Università degli Studi di Padova. In addition, Huygens gives planetary scientists a wealth of 'ground-truth' to complement and help interpret the observations still coming from Cassini. At the beginning of 2007, Cassini showed that liquid methane is present on Titan in lakes.

Cassini, whose experiments also see a joint US and European participation, will make another 22 fly-bys of Titan - the first on 13 January - between now and the end of its scheduled mission in the summer of 2008. The Cassini-Huygens scientists are discussing their options to extend the mission. One idea, says Christophe Sotin, Université de Nantes, France, would be to use Cassini to study the newly discovered lakes.

Huygens has exceeded expectations and shown Titan to be an 'alien earth', giving planetary scientists a new world of fascination to explore.

Note to editors:

Cassini-Huygens is a project of international collaboration between NASA, ESA and ASI.

For more information

Jean-Pierre Lebreton, ESA Huygens Project Scientist

Email : jean-pierre.lebreton @ esa.int