9 min read

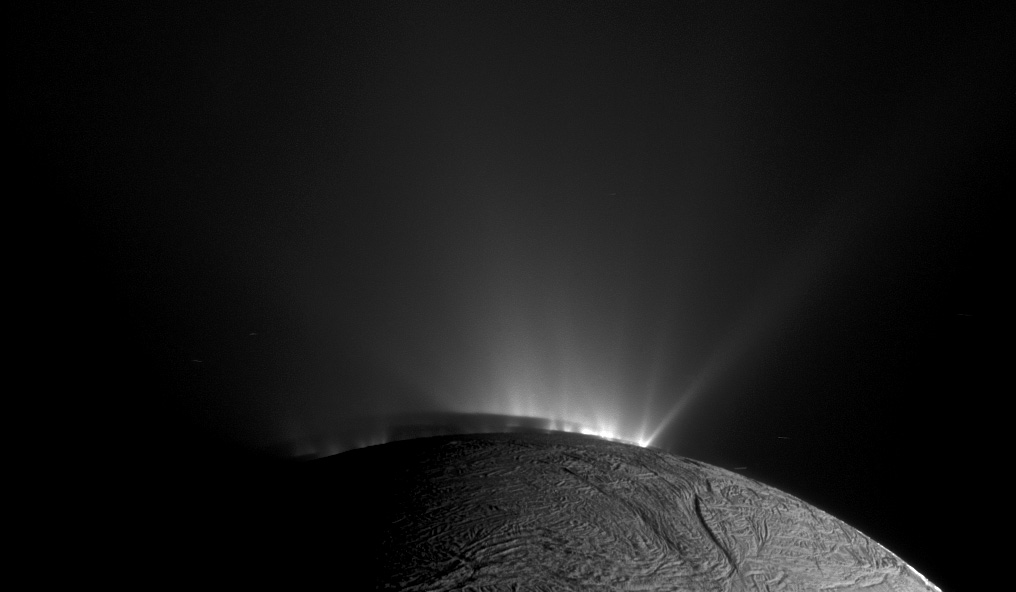

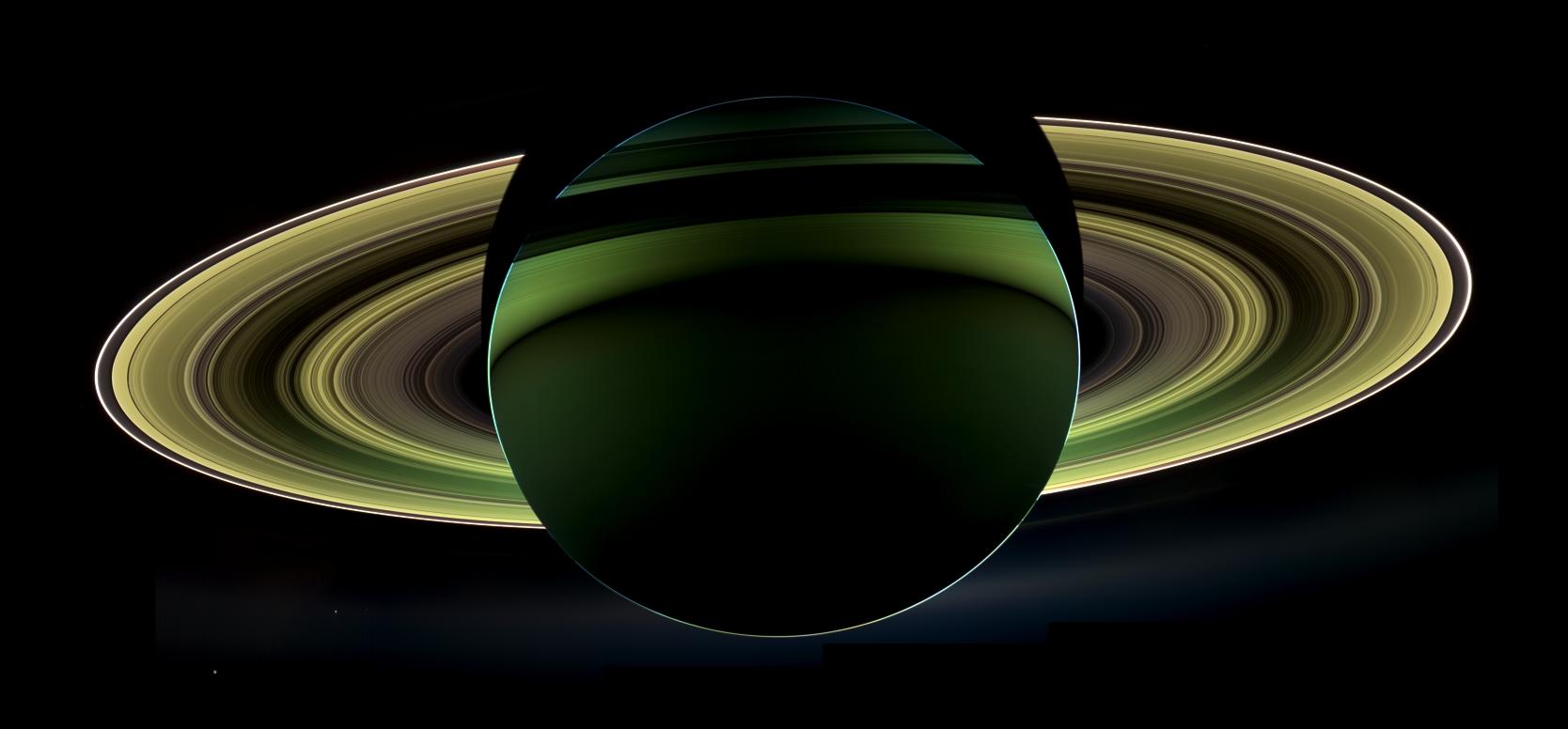

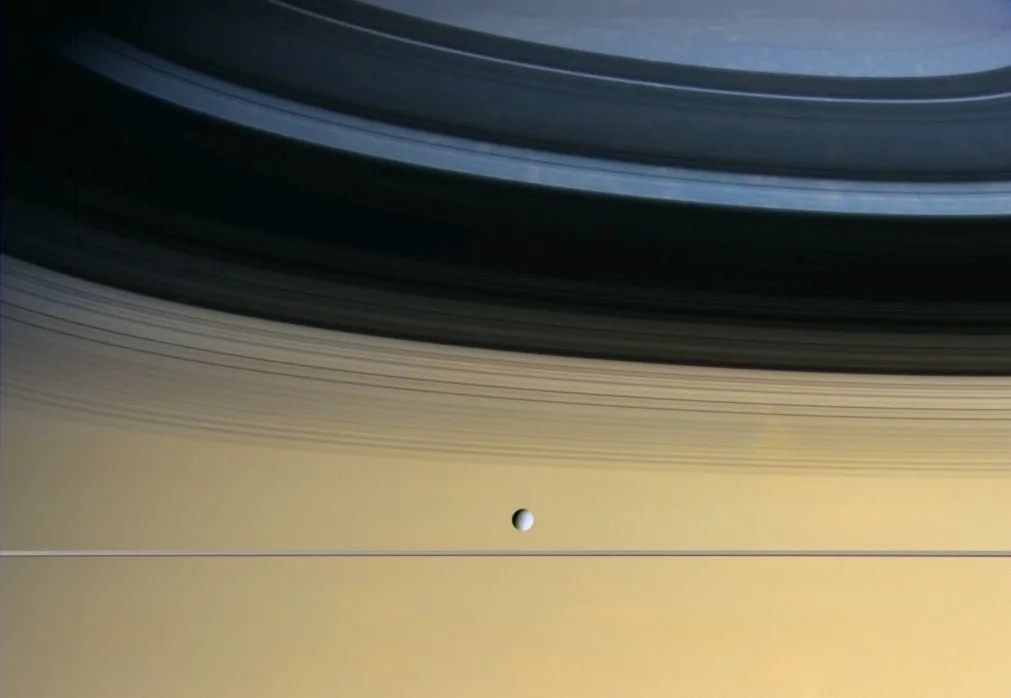

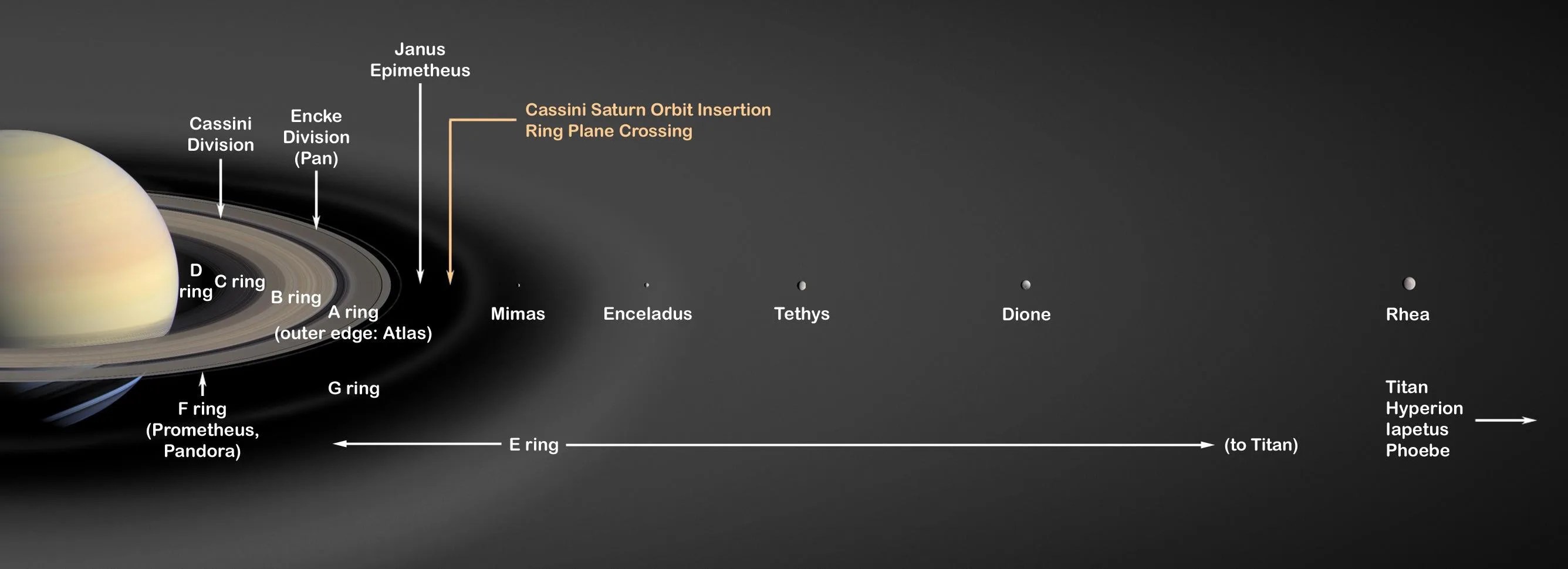

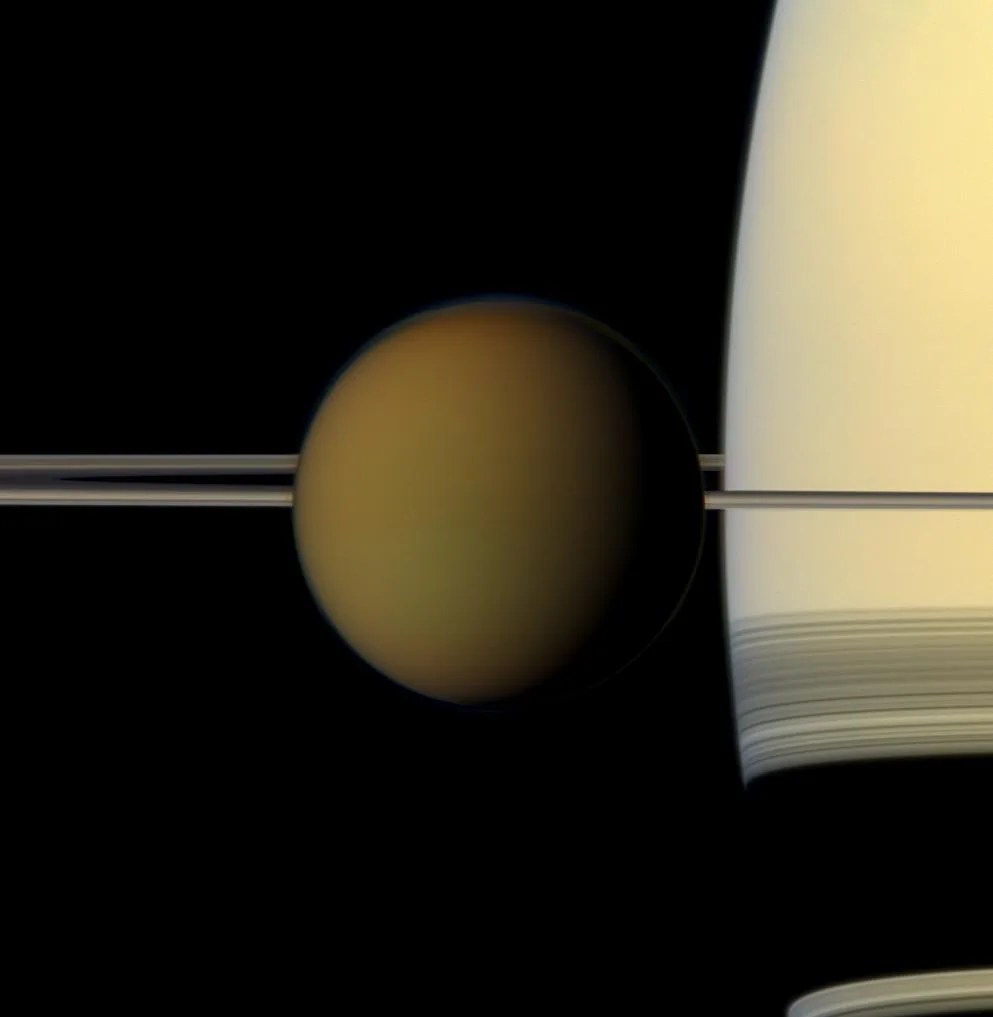

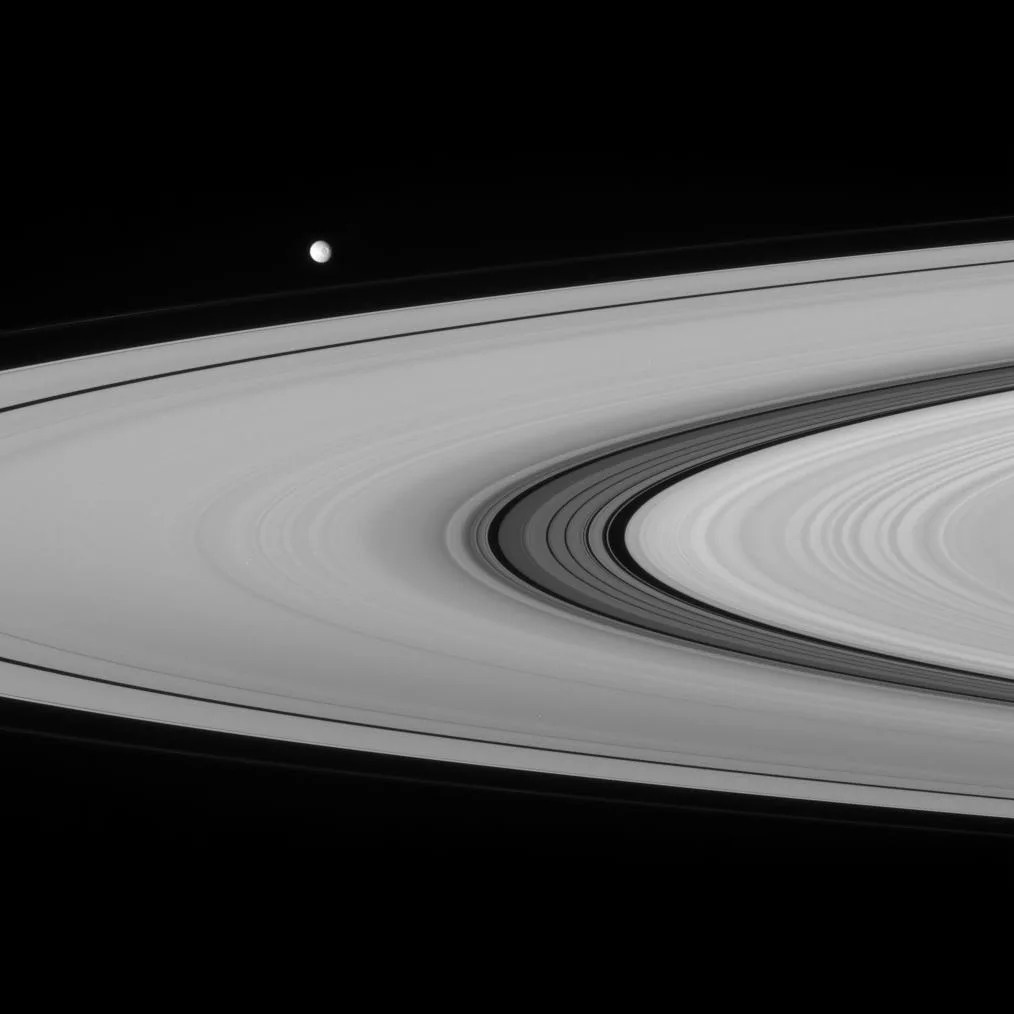

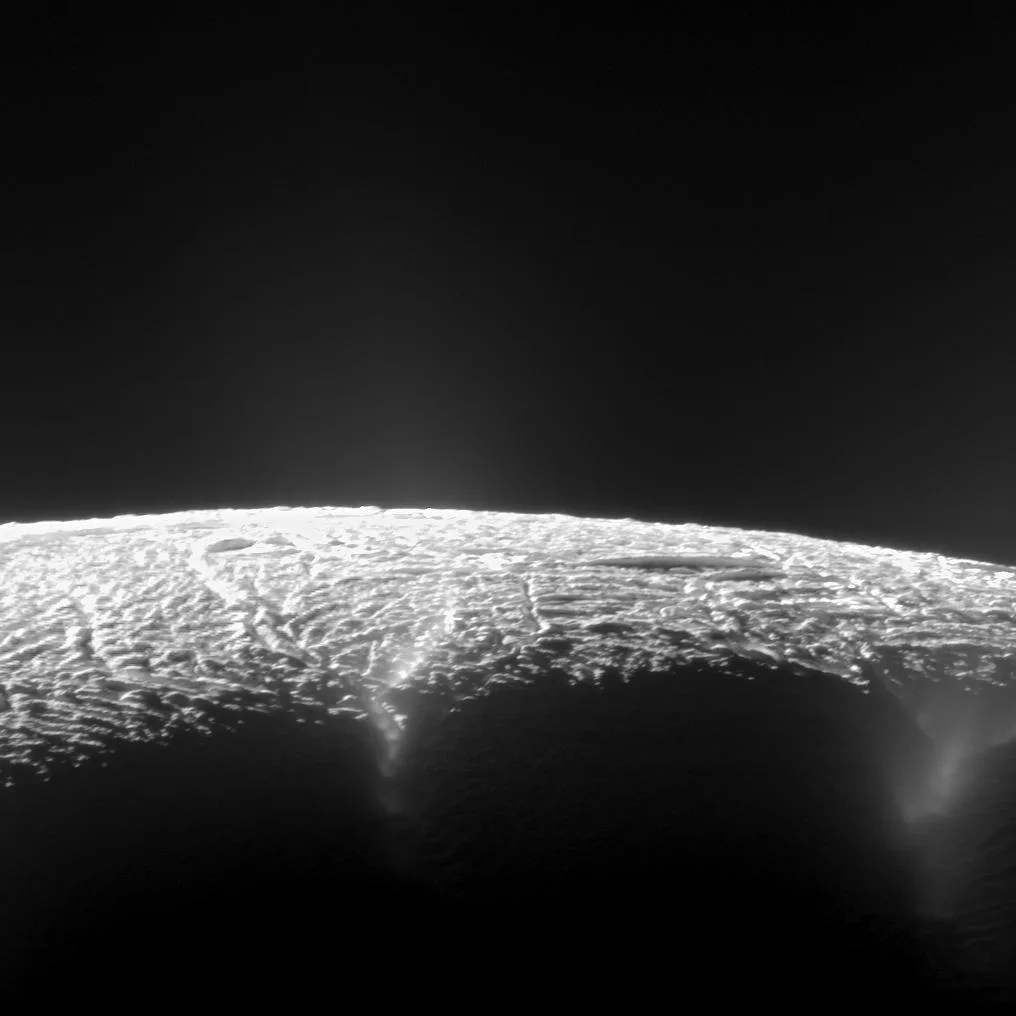

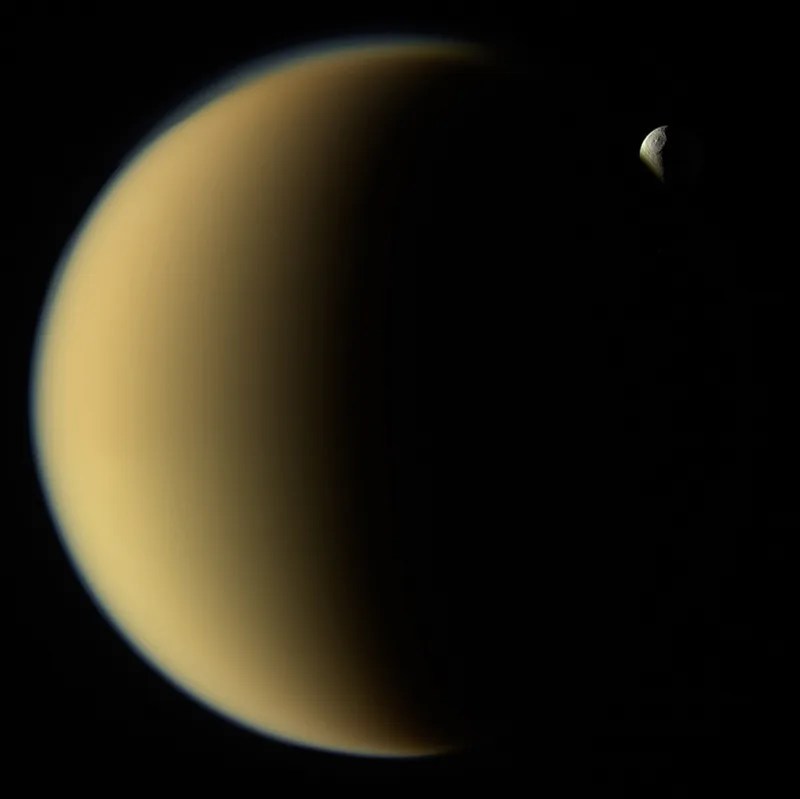

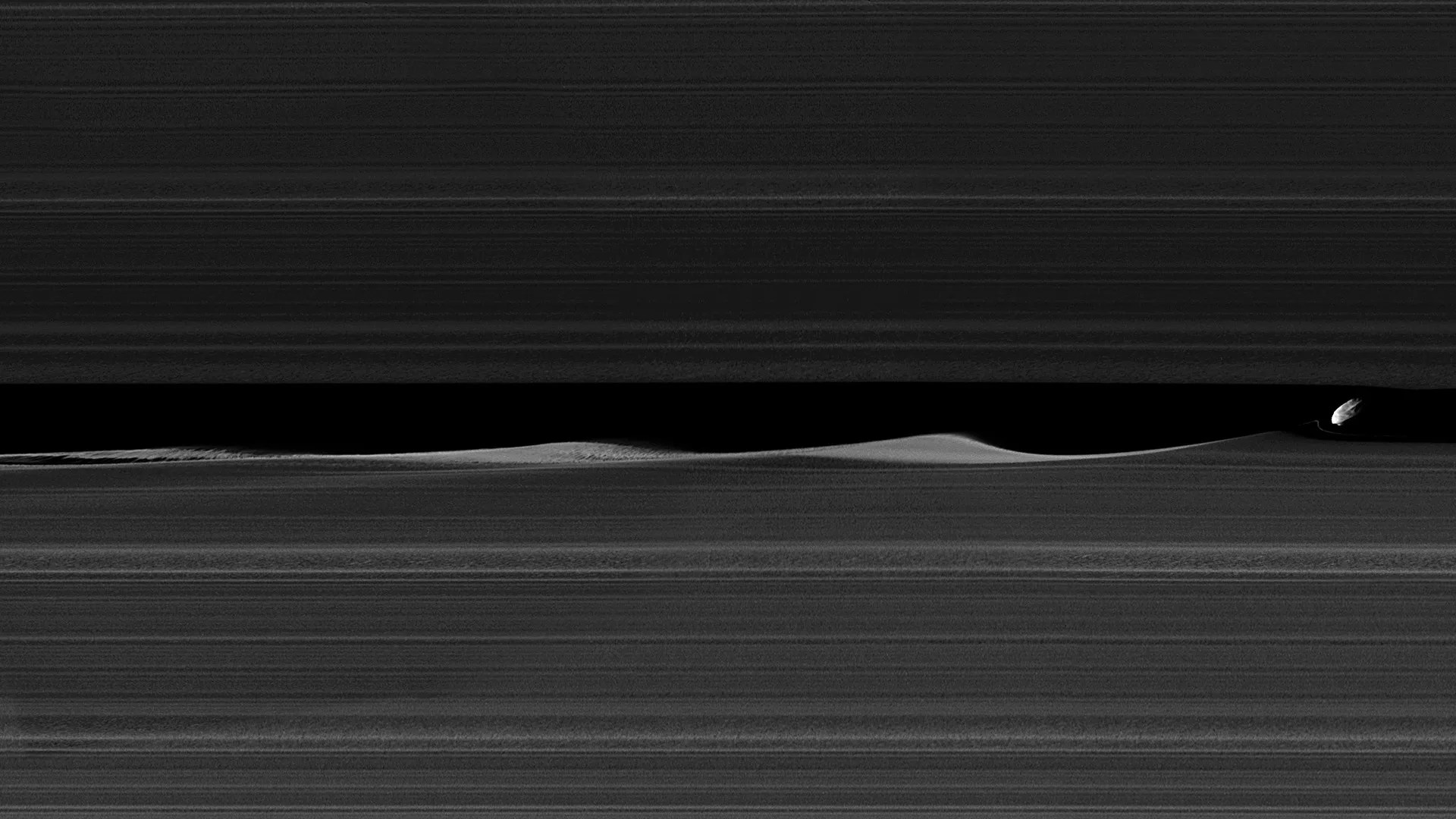

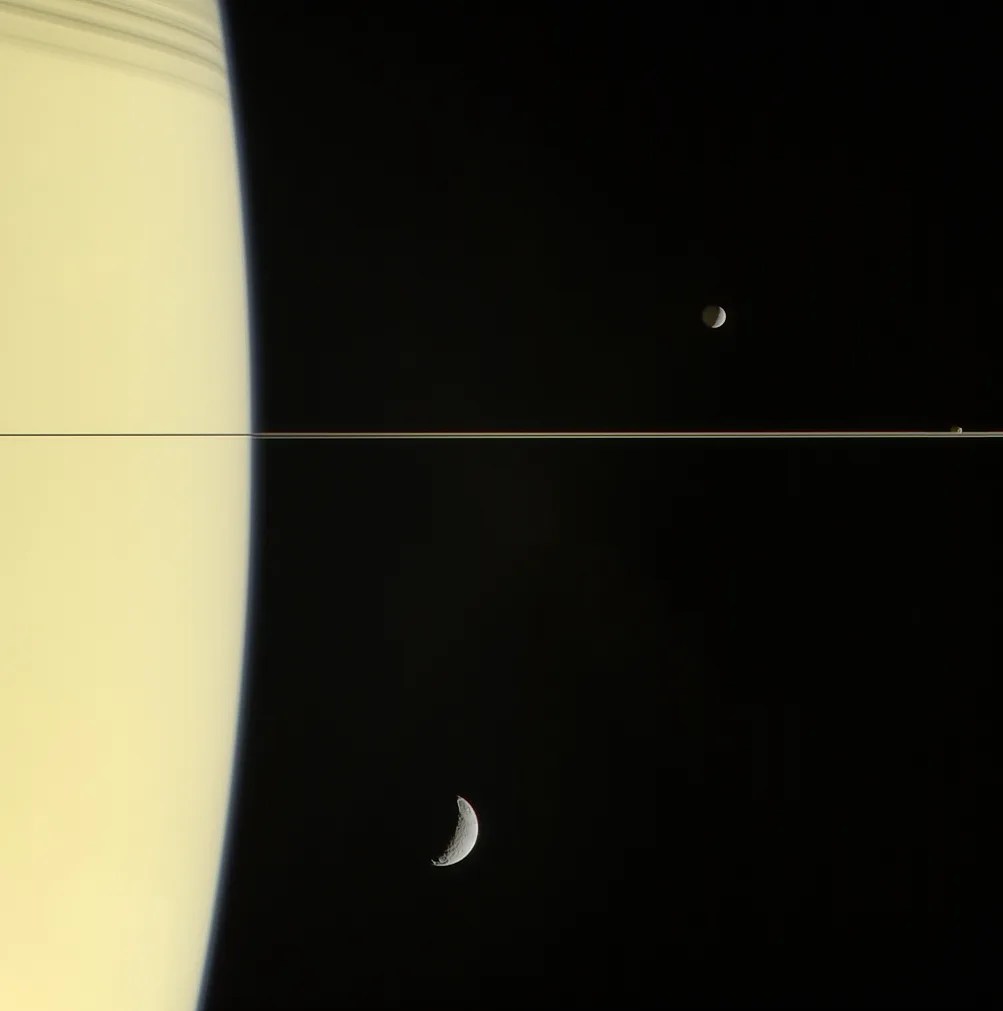

There’s way more to Saturn than its majestic rings. The planet also boasts a collection of dozens of exotic moons. Titan – a giant, icy world bigger than our Moon – is known for its dense, hazy atmosphere and methane seas. There’s also Enceladus, a bright, white ice ball with a liquid-water ocean wrapped inside its frozen shell, that continuously erupts as a towering water plume through cracks near its south pole. Saturn’s moon Pan, nestled in the planet’s rings, is known for looking like a ravioli, and Janus looks like a meatball. Cassini scientists even spotted an object orbiting inside the rings, nicknamed Peggy, that might have been a moon in the act of forming or disintegrating.

While we've learned some amazing things about these moons, there are many open questions about Saturn’s coterie of satellites and what they can teach us about the evolution of the solar system.

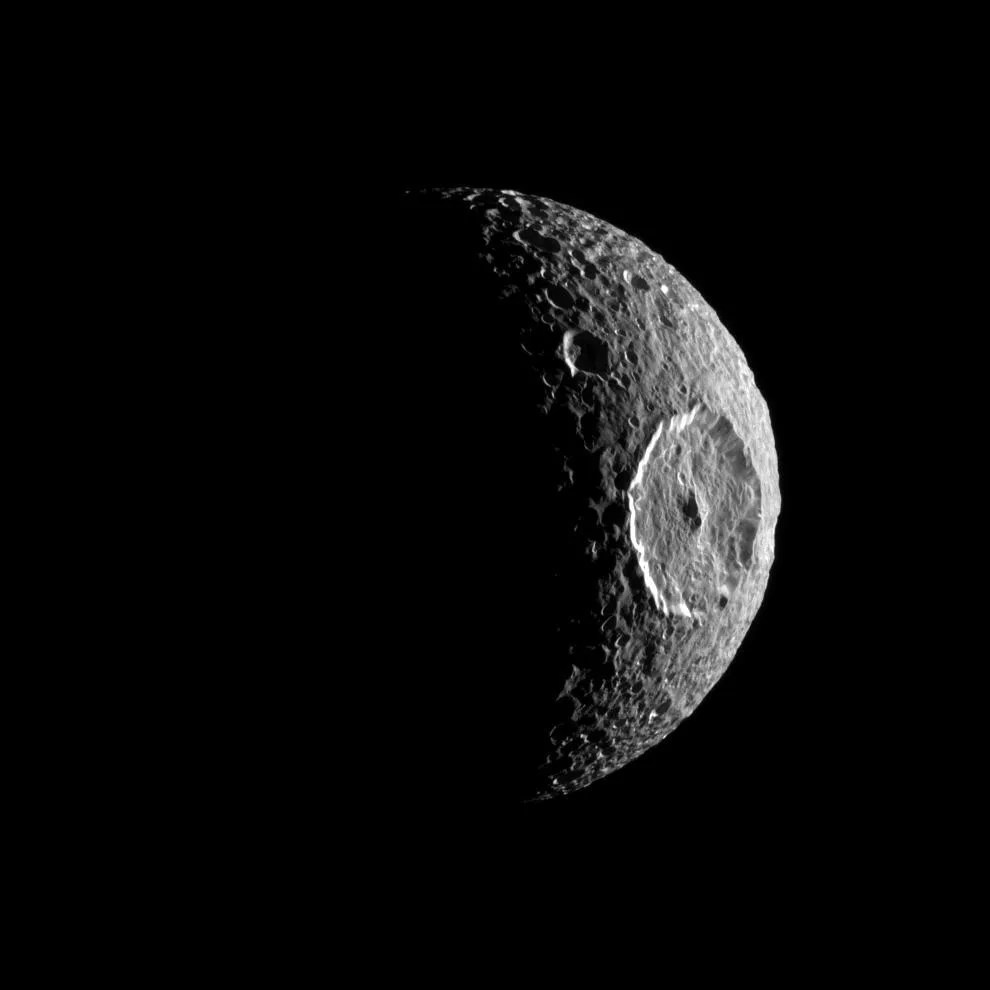

Many of Saturn's satellites, or moons, formed at the same time as the rest of our solar system, more than 4 billion years ago. Saturn's larger moons, in particular, display a record of that long history in the vast craters that cover their surfaces. But recent modeling suggests some of Saturn’s moons may be younger, possibly only 100 million years old or less.

One way scientists can tell the ages of the moons is by looking at how closely the moons orbit the planet. A gravitational tug-of-war between planets and their satellites pushes the orbits of satellites outward into space slowly over very long periods of time. For example, our Moon is drifting away from Earth each year at about the rate that fingernails grow. One study suggests that if Saturn’s moons were as old as the solar system, the moons that are close to the rings would’ve drifted much farther away by now. This conclusion conflicts with the apparent age of the moons from their heavily cratered surfaces, but it adds new ideas to the ongoing quest to puzzle out the history of the Saturn system.

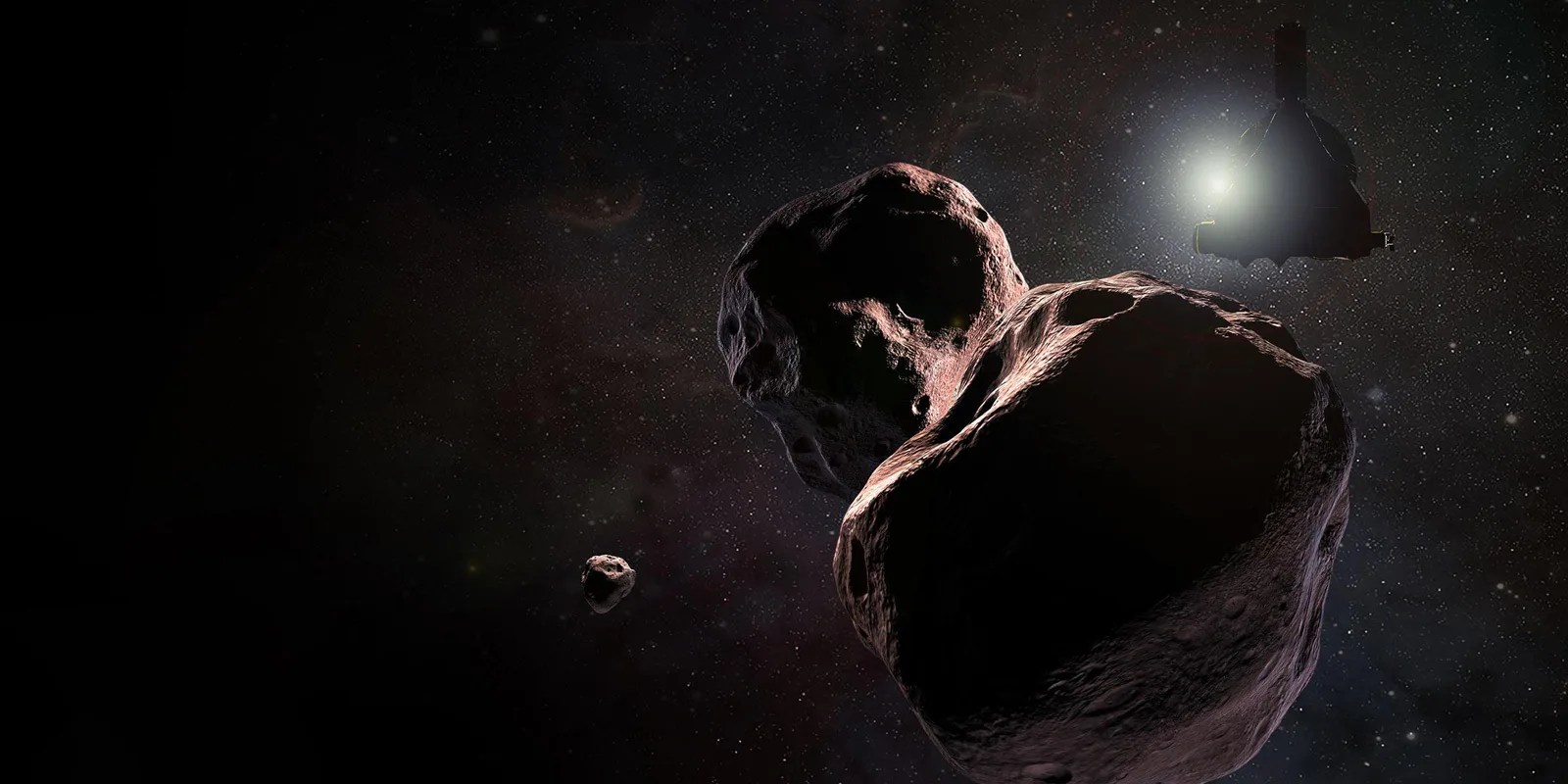

We don’t think so. In fact, there are moonlets still forming today at the outer edge of Saturn’s rings. Some of Saturn’s moons, including its smallest and innermost major satellite, Mimas, might have formed from the same material that made Saturn's iconic rings – which also may be much younger than previously thought. This material could include pieces of comets and asteroids that broke up around Saturn. Or maybe early moons shattered into pieces after colliding or straying too close to Saturn where they were ripped apart by the tugging of the giant planet’s gravity. Another theory is that the planets rearranged a billion years or so after the solar system formed and stirred up the small bodies around them, flinging them all over the place – potentially, a great recipe for new moons.

It also appears that Saturn adopted some moons. The pockmarked Phoebe likely came from afar and was captured by Saturn’s gravity at some point. We think so because Phoebe is made out of material found in the far reaches of the solar system, way beyond Saturn. It also orbits much farther from Saturn than most other moons, and it circles the planet in the opposite direction – in what is called a retrograde orbit – compared to most other satellites. Saturn also has quite a few small, outer moons in retrograde orbits that are tilted with respect to the planet's equator, sure signs that these are likely captured objects that didn't form with the other moons.

Jupiter, a gas giant even bigger than Saturn, has four large moons and dozens of smaller ones. These are the “Galilean moons,” a group named after Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei, who discovered them in January 1610. The Galilean moons are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Saturn has only one moon in this size category: Titan. We don’t know why Jupiter’s large moons stayed intact while most of Saturn’s appear to have been shredded by Saturn’s gravity and collisions. One possibility is that, because Jupiter’s large satellites orbit farther away from the planet, they are potentially less susceptible to being ripped apart by its gravity.

This is where the ages of the moons may come into play. Thanks to NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, which studied Saturn and its moons for a decade from up close, we know that Enceladus, Titan, and possibly Dione have liquid water oceans. But why not Mimas? It is much closer to Saturn than Enceladus, and thus more susceptible to the tidal tug-of-war between those two bodies that could generate enough heat to maintain a liquid ocean inside Mimas. However, if Mimas were to turn out to be relatively young, that could explain why it’s dry, speculates planetary scientist Marc Neveu in a paper in Nature Astronomy.

According to his research, Mimas could be less than 1 billion years old, forming from loose material in Saturn’s rings. In this hypothetical scenario, by the time the debris coalesced into Mimas, it would already have had billions of years to lose its radioactive heat (heat produced by the nuclear decay of certain chemical elements in rocks over eons). Without radioactive heat inside, the cold and rigid sphere of Mimas would never have been squished and warmed enough by Saturn’s pull to have melted its ice into a liquid-water ocean. Still, there is some evidence that an ocean on Mimas is possible. Cassini found that the little moon wobbles as it rotates on its axis, an enigma that could be explained by either an irregularly shaped solid core or from an ocean sloshing beneath its icy surface.

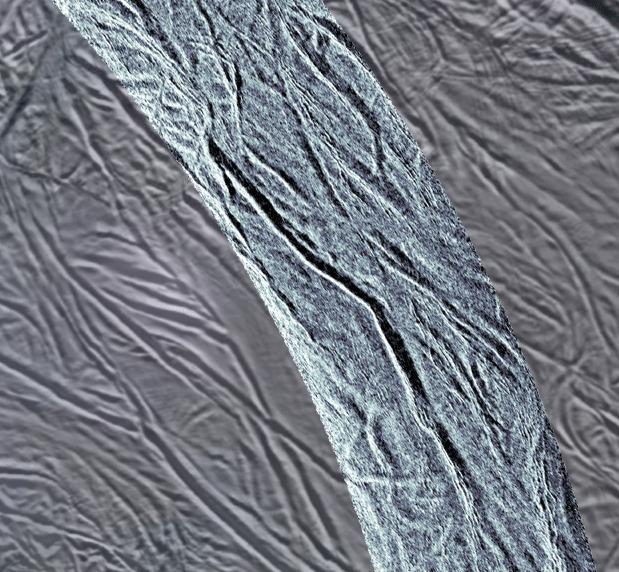

The ocean on Enceladus is salty like Earth’s ocean. The salinity suggests that the water might be interacting chemically with a rocky core – increasing the likelihood the ocean could be habitable for simple life. This type of interaction on our planet provides energy and nutrients to critters that thrive on the dark seafloor, miles below the ocean surface. Could the same thing be happening on Enceladus? Titan also has a liquid-water ocean, but scientists don’t know yet if it’s interacting with rock on the ocean bottom or with ice.

Most likely they've been around for billions of years, as it is very difficult for a subsurface ocean to form after the moon forms. Scientists have yet to zero in on a solid explanation for what originally formed Enceladus’s ocean, although a giant impact has been examined as a possibility. Titan’s ocean, on the other hand, could have formed around the same time as the moon, more than 4 billion years ago. It could’ve been melted by radioactive decay heat in Titan's deep interior, by heat from impacts, or some combination of these. The heat generated by gravitational tugging is not a major factor on Titan since its orbit is so far from Saturn.

We don’t know yet if the oceans inside Saturn's moons have the necessary ingredients to support life, but there are intriguing signs they might. Enceladus is among NASA’s top targets in the search for life beyond Earth because it appears to have three of life’s most important ingredients: liquid water, the right chemical ingredients (such as carbon or hydrogen), and an energy source.

Near the end of its mission in 2015, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft flew through a plume of water erupting from Enceladus and detected molecular hydrogen. This helped strengthen the case for habitability on Enceladus because hydrogen is an important food source for life-forms that thrive near hydrothermal vents on Earth. In June 2023, also using data from Cassini, an international team of scientists discovered phosphorus – another essential chemical element for life – locked inside salt-rich ice grains ejected into space from Enceladus. Previous analysis of Enceladus’ ice grains revealed concentrations of sodium, potassium, chlorine, and carbonate-containing compounds.

Titan, which is half the size of Earth, is intriguing not only for its internal ocean but also for its dense, nitrogen-rich atmosphere and complex carbon chemistry. Whether it's inhabited or not, Titan is a fantastic natural laboratory for the chemistry of life.

It’s likely Saturn's major moons will orbit the planet forever, but some of the smaller, more fragile ring moons could vanish. Newer moonlets, created from loose material in the rings, are at higher risk for destructive collisions and disruption by gravitational tides.

Over time, moons tend to slowly drift away from their parent planets: it’s nature. At Saturn, the gravity from its many moons tugs on the planet’s insides, drawing them a little closer to the moons. (Similar to how our Moon’s gravity tugs on Earth’s oceans, creating tides.) But Saturn’s gravity also tugs on the moons. This creates a tug-of-war that forces the moons into increasingly wider orbits, pushing them farther from Saturn – like kids on a fast-spinning merry-go-round being tugged toward its edge.

One analysis by a group of researchers outside NASA suggested some of Saturn's inner moons might be moving outward faster than expected, given how close to the planet they are. The scientists compared a decade of Cassini measurements of the orbits of Saturn’s moons to their orbits in 100-year-old telescope images preserved on photographic plates. Their analysis suggested a young age for the moons, otherwise, they would’ve drifted much farther from Saturn in the 4.6 billion years since Saturn formed. While the idea is intriguing, Cassini researchers point out that it's unlikely 100 years of observations would be long enough to discern changes in the orbits of these moons.

So are they drifting away? In a sense, yes, just like Earth's Moon is. However, the amount of time involved is likely greater than the predicted lifespan of the solar system (i.e., many billions of years).

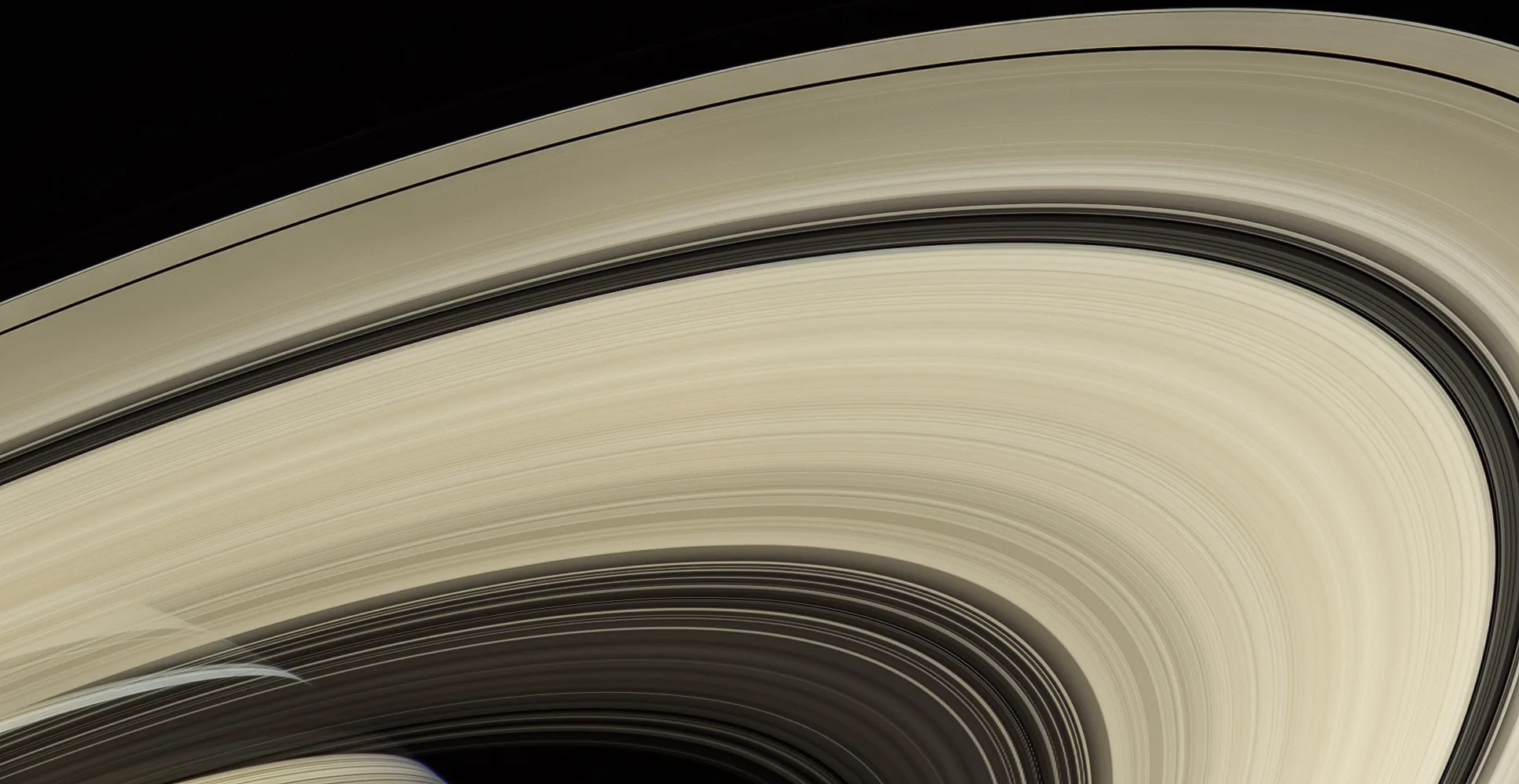

In essence, they’re disappearing, and so are the moonlets living among them. Researchers think they could be gone in possibly only 100 million years. The rings are being pulled into Saturn by gravity as a gradual, steady rain of dust-size ice particles.