By Ann Jenkins, Space Telescope Science Institute

While we now know of thousands of exoplanets — planets around other stars — the vast majority of our knowledge is indirect. That is, scientists have not actually taken many pictures of exoplanets, and because of the limits of current technology, we can only see these worlds as points of light. However, the number of exoplanets that have been directly imaged is growing over time. When NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope launches in 2021, it will open a new window on these exoplanets, observing them in wavelengths at which they have never been seen before and gaining new insights about their nature.

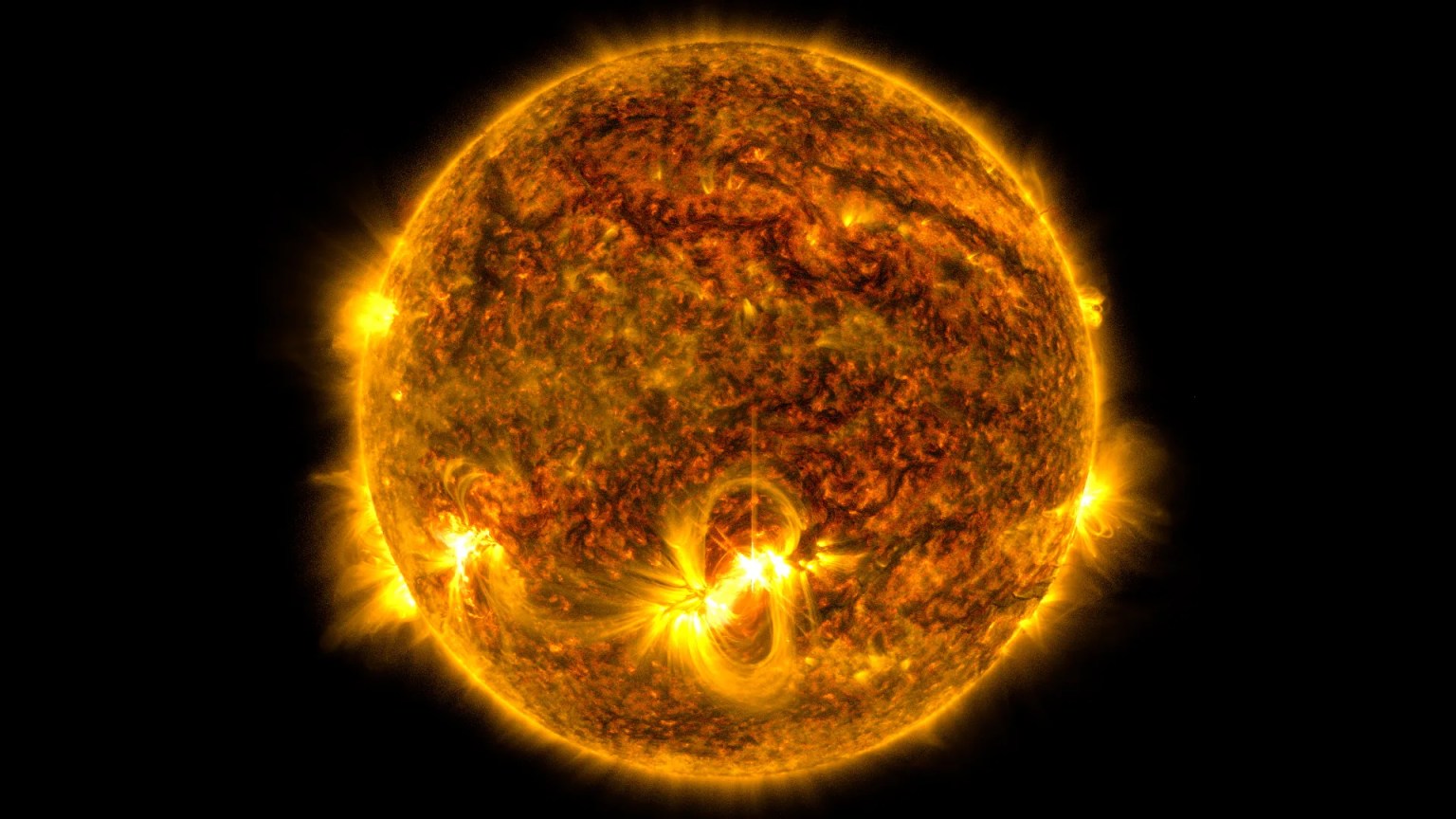

Exoplanets are close to much brighter stars, so their light is generally overwhelmed by the light of the host stars. Astronomers usually find an exoplanet by inferring its presence based on the dimming of its host star’s light as the planet passes in front of the star – an event called a “transit.” Sometimes a planet tugs on its star, causing the star to wobble slightly.

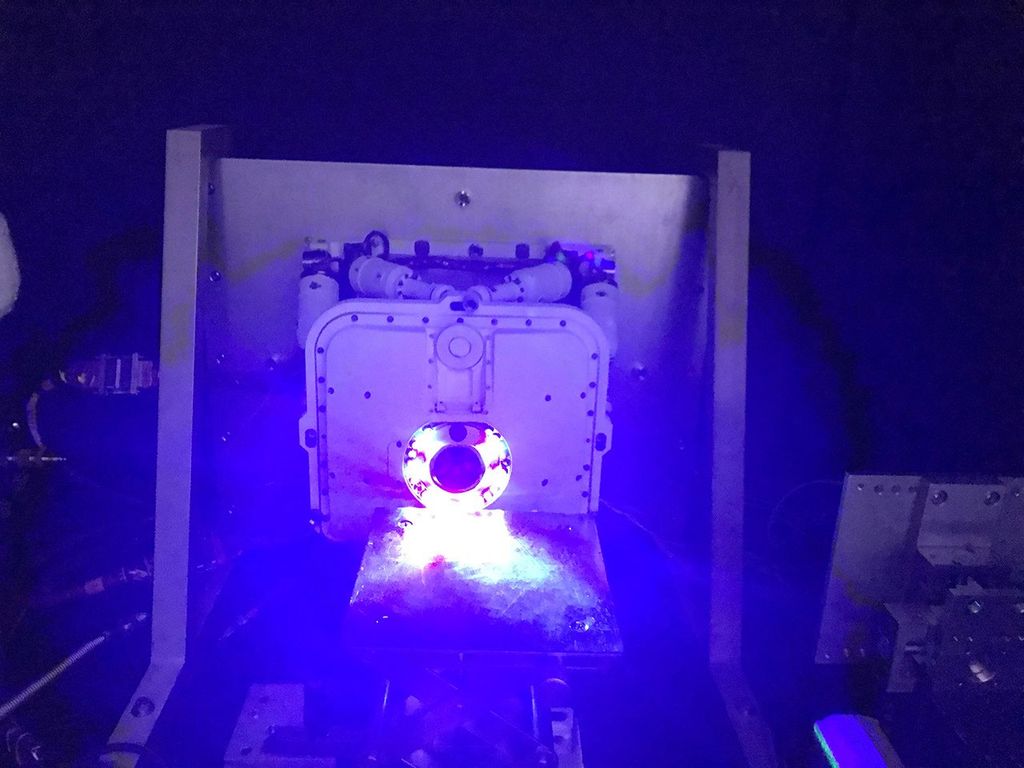

In a few cases, scientists have captured pictures of exoplanets by using instruments called coronagraphs. These devices block the glare of the star in much the same way you might use your hand to block the light of the Sun. However, finding exoplanets with this technique has proven to be very difficult. All that will change with the sensitivity of Webb. Its onboard coronagraphs will allow scientists to view exoplanets at infrared wavelengths they’ve never seen them in before.

Webb’s Unique Capabilities

Coronagraphs have something important in common with eclipses. During an eclipse, the Moon blocks the light of the Sun, allowing us to view stars that would normally be overwhelmed by the Sun’s glare. Astronomers took advantage of this during the 1919 eclipse, 100 years ago on May 29, in order to test Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity. Similarly, a coronagraph acts as an “artificial eclipse” to block the light from a star, allowing planets that would otherwise be lost in the star’s glare to be seen.

“Most of the planets that we have detected so far are roughly 10,000 to 1 million times fainter than their host star,” explained Sasha Hinkley of the University of Exeter. Hinkley is the principal investigator on one of Webb’s first observation programs to study exoplanets and exoplanetary systems.

“There is, no doubt, a population of planets that are fainter than that, that have higher contrast ratios, and are possibly farther out from their stars,” Hinkley said. “With Webb, we will be able to see planets that are more like 10 million, or optimistically, 100 million times fainter.” To observe their targets, the team will use high-contrast imaging, which discerns this large difference in brightness between the planet and the star.

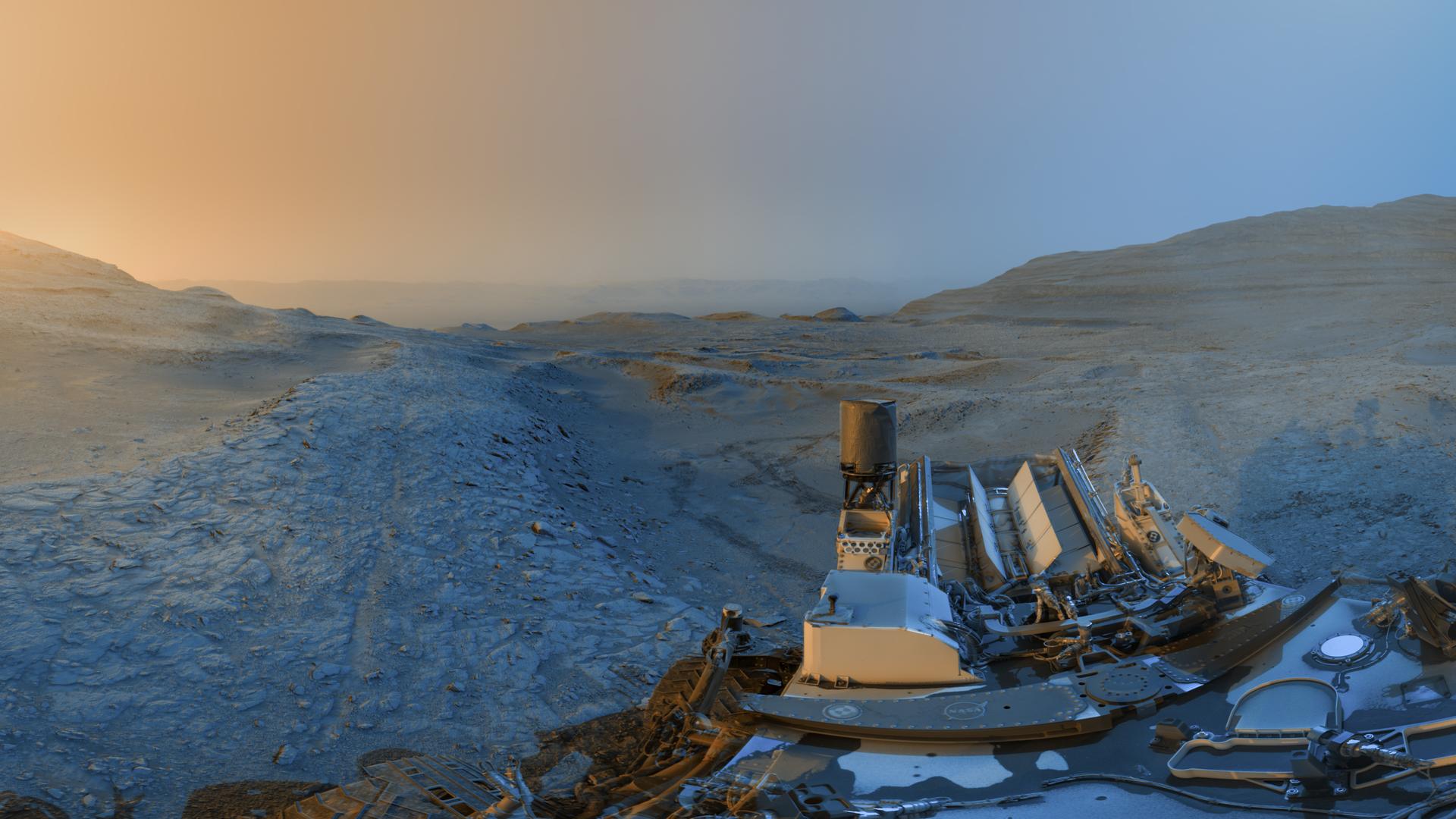

Webb will have the capability of observing its targets in the mid-infrared, which is invisible to the human eye, but with sensitivity that is vastly superior to any other observatory ever built. This means that Webb will be sensitive to a class of planet not yet detected. Specifically, Saturn-like planets at very wide orbital separations from their host star may be within reach of Webb.

“Our program is looking at young, newly formed planets and the systems they inhabit,” explained co-principal investigator Beth Biller of the University of Edinburgh. “Webb is going to allow us to do this in much more detail and at wavelengths we’ve never explored before. So it’s going to be vital for understanding how these objects form, and what these systems are like.”

Testing the Waters

The team’s observations will be part of the Director's Discretionary-Early Release Science program, which provides time to selected projects early in the telescope's mission. This program allows the astronomical community to quickly learn how best to use Webb's capabilities, while also yielding robust science.

“With our ERS program, we will really be ‘testing the waters’ to get an understanding of how Webb performs,” said Hinkley. “We really need the best understanding of the instruments, of the stability, of the most effective way to post-process the data. Our observations are going to tell our community the most efficient way to use Webb.”

NASA, ESA, and J. Olmsted (STScI)

The Targets

Hinkley’s team will use all four of Webb’s instruments to observe three targets: A recently discovered exoplanet; an object that is either an exoplanet or a brown dwarf; and a well-studied ring of dust and planetesimals orbiting a young star.

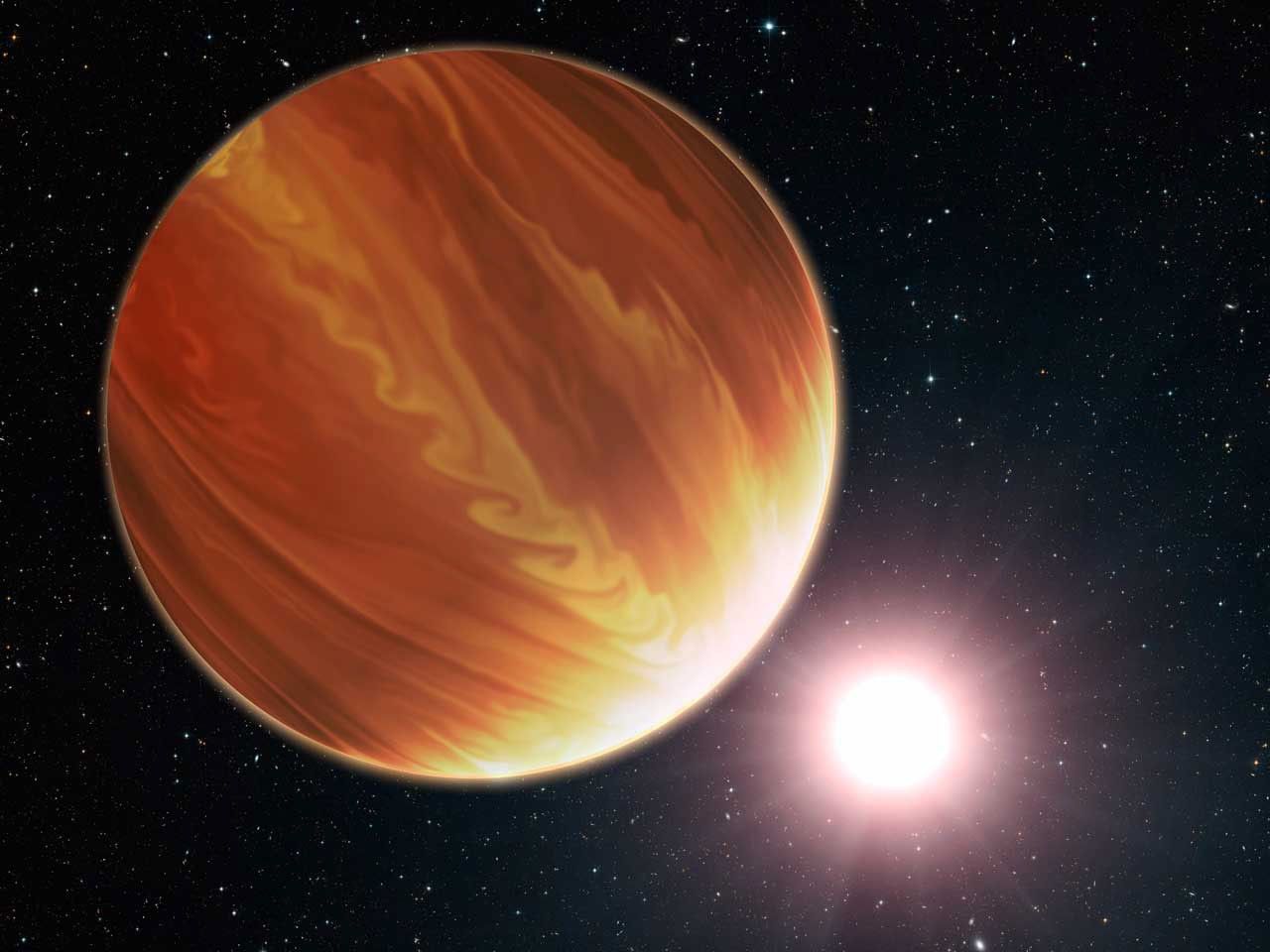

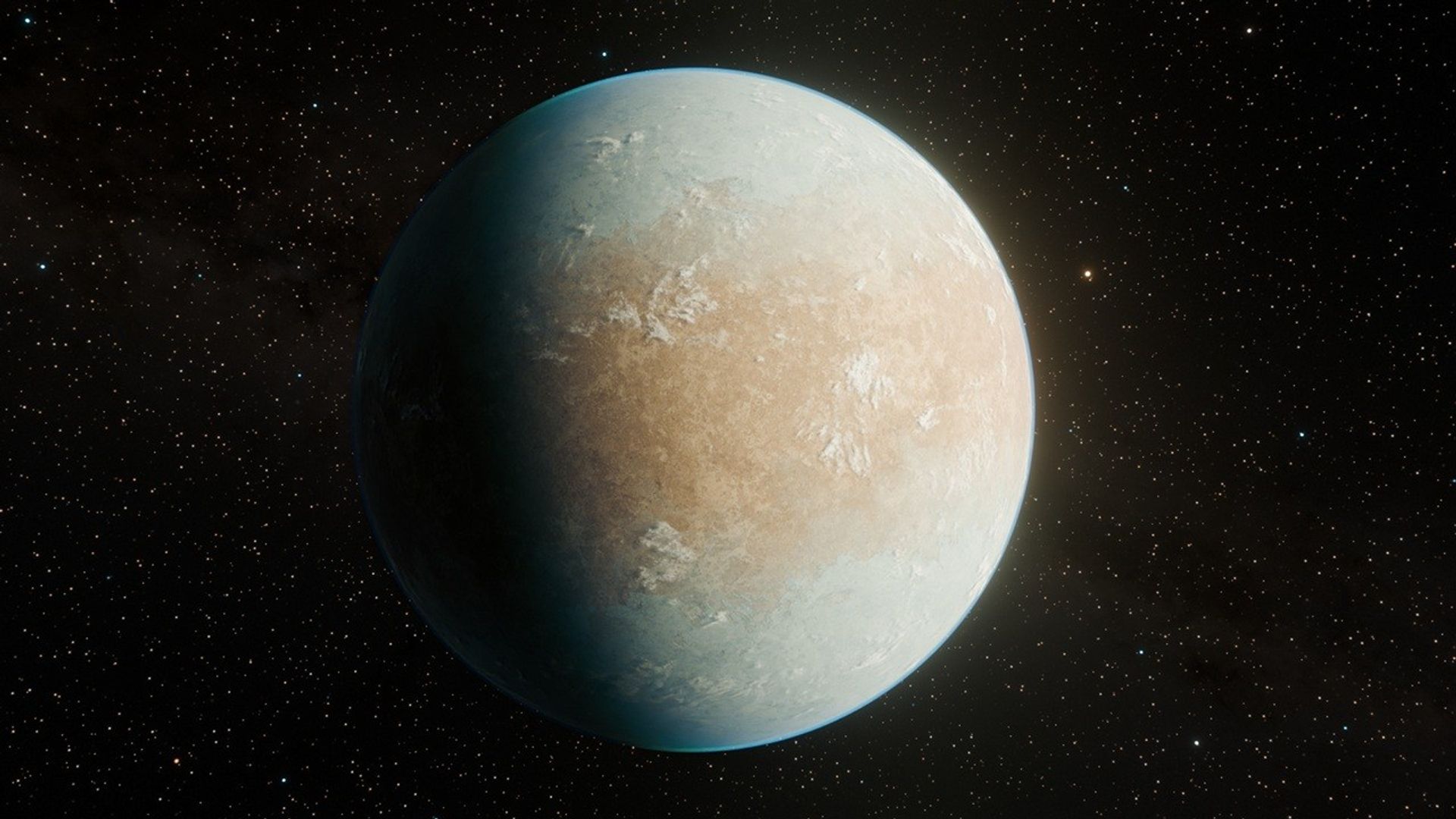

Exoplanet HIP 65426b: This newly discovered, directly imaged exoplanet has a mass between six and 12 times that of Jupiter and is orbiting a star that is hotter than and about twice as massive as our Sun. The exoplanet is roughly 92 times farther from its star than Earth is from the Sun. The wide separation of this young planet from its star means that the team’s observations will be much less affected by the bright glare of the host star. Hinkley and his team plan to use Webb’s full suite of coronagraphs to view this target.

Planetary-mass companion VHS 1256b: An object somewhere around the planet/brown dwarf boundary, VHS 1256b also is widely separated from its red dwarf host star—about 100 times the distance that the Earth is from the Sun. Because of its wide separation, observations of this object are much less likely to be affected by unwanted light from the host star. In addition to high-contrast imaging, the team expects to get one of the first "uncorrupted" spectra of a planet-like body at wavelengths where these objects have never before been studied.

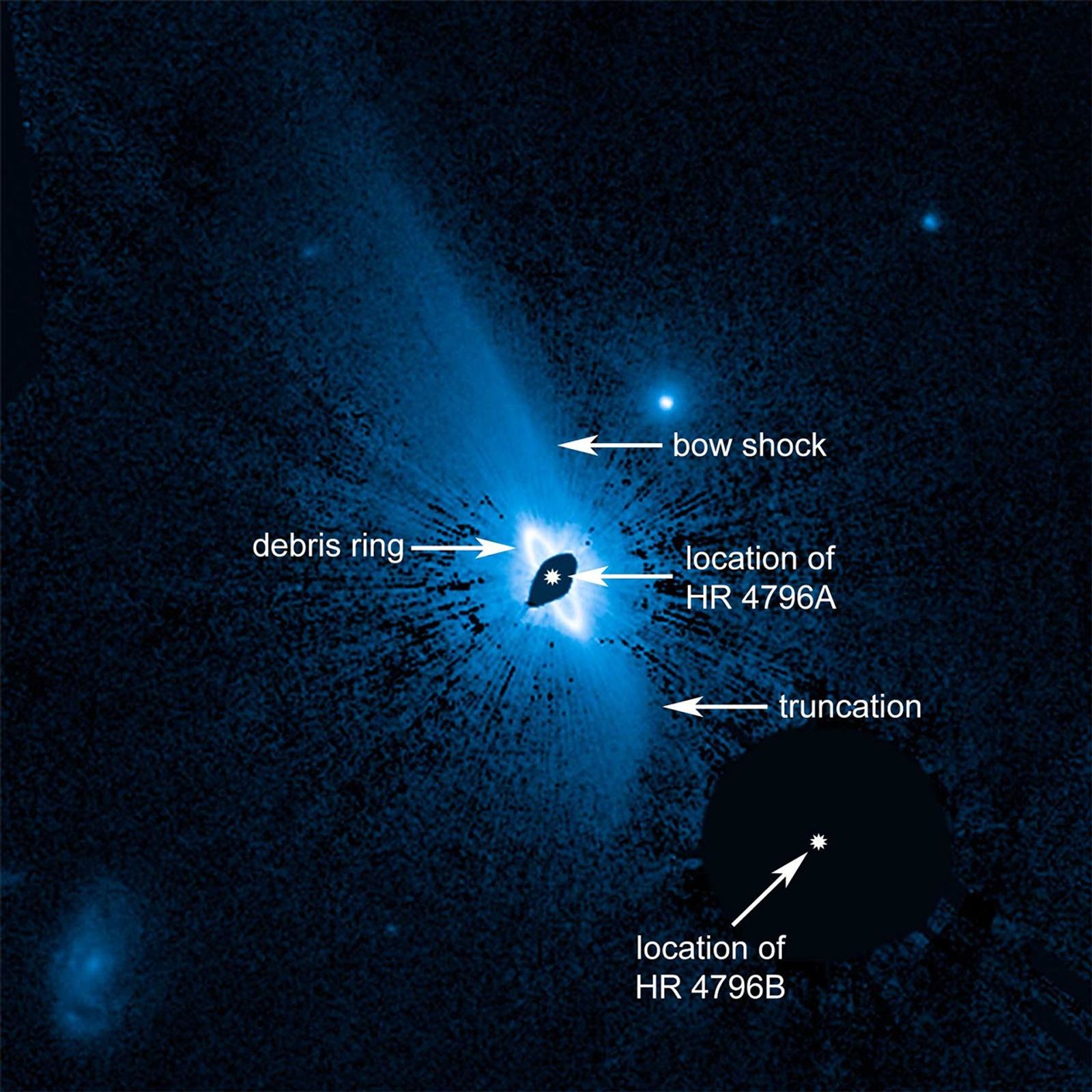

Circumstellar debris disk: For more than 20 years, scientists have been studying a ring of dust and planetesimals orbiting a young star called HR 4796A, which is about twice as massive as our own Sun. Astronomers think that most planetary systems probably looked a lot like HR 4796A and its debris ring at their earliest ages, making this a particularly interesting target to study. The team will use the high-contrast imaging of Webb’s coronagraphs to view the disk in different wavelengths. Their goal is to see if the structures of the disk look different from wavelength to wavelength.

NASA, ESA, and L. Hustak (STScI)

Planning the Program

To plan this Early Release Science program, Hinkley asked as many members of the astronomical community as possible the simple question: If you want to plan a survey to search for exoplanets, what are the questions that you need the answers to for planning your surveys?

“What we came up with was a set of observations that we think is going [to] answer those questions. We are going to tell the community that this is the way Webb performs in this mode, this is the kind of sensitivity we get, and this is the kind of contrast we achieve. And we need to rapidly turn that around and inform the community so that they can prepare their proposals really, really quickly.”

The team is excited to view their targets in wavelengths never before detected, and to share their knowledge. According to Biller, “We could see years ago that for some of the planets we’ve already discovered, Webb would be really transformational.”

The James Webb Space Telescope will be the world’s premier space science observatory when it launches in 2021. Webb will solve mysteries in our solar system, look beyond to distant worlds around other stars, and probe the mysterious structures and origins of our universe and our place in it. Webb is an international program led by NASA with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Canadian Space Agency.