The cores of gas giant planets, like our own Jupiter, are shrouded in dense, turbulent atmospheres – and so are shrouded in mystery. A newly discovered world called TOI 849 b could be the exposed, naked core of a gas giant whose atmosphere was blasted away by its star.

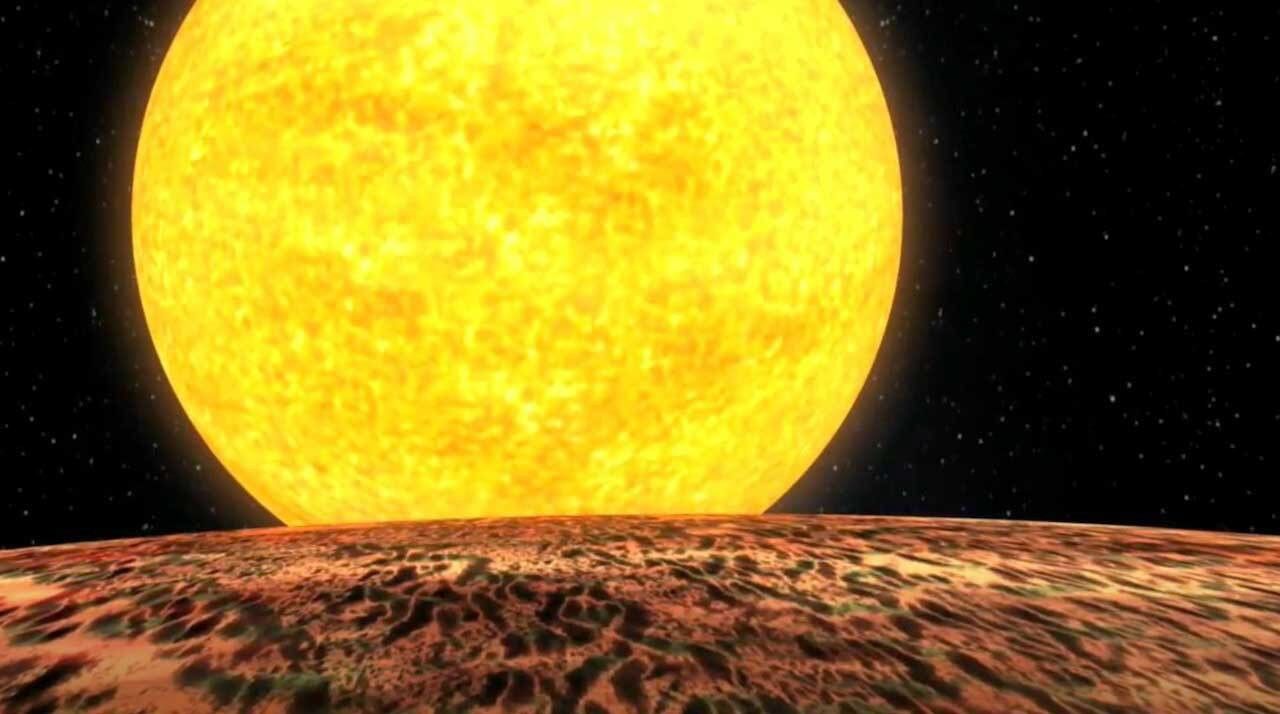

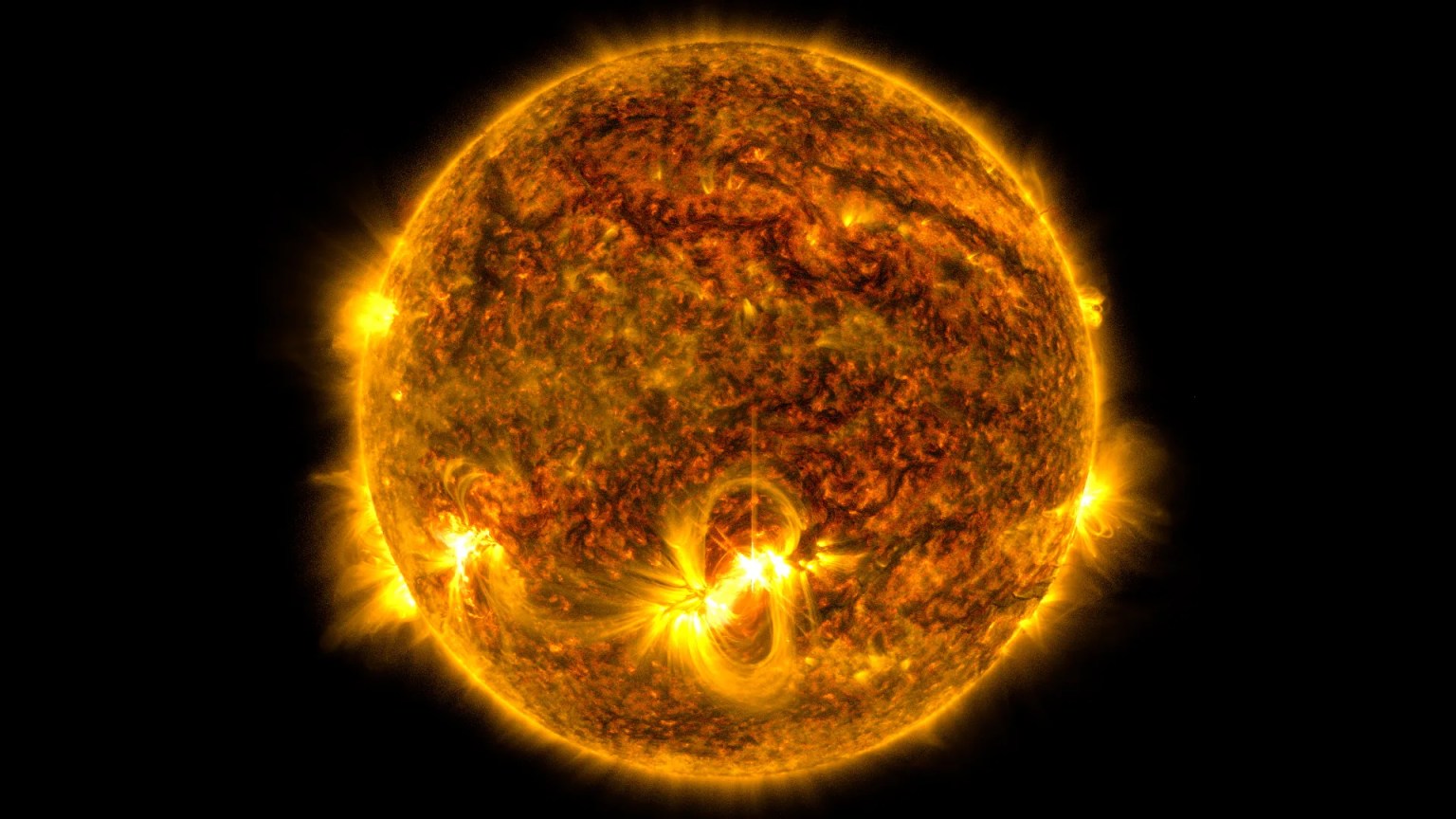

Every day is a bad day on planet TOI 849 b. About half the mass of our own Saturn, this planet orbits a Sun-like star more than 700 light-years from Earth. It hugs its star so tightly that a year – one trip around the star – takes less than a day. And it pays a high price for this close embrace: an estimated surface temperature of nearly 2,800 degrees Fahrenheit, which is 1,500 degrees Celsius. It's a scorcher even compared to Venus, which is 880 degrees Fahrenheit (471 degrees Celsius).

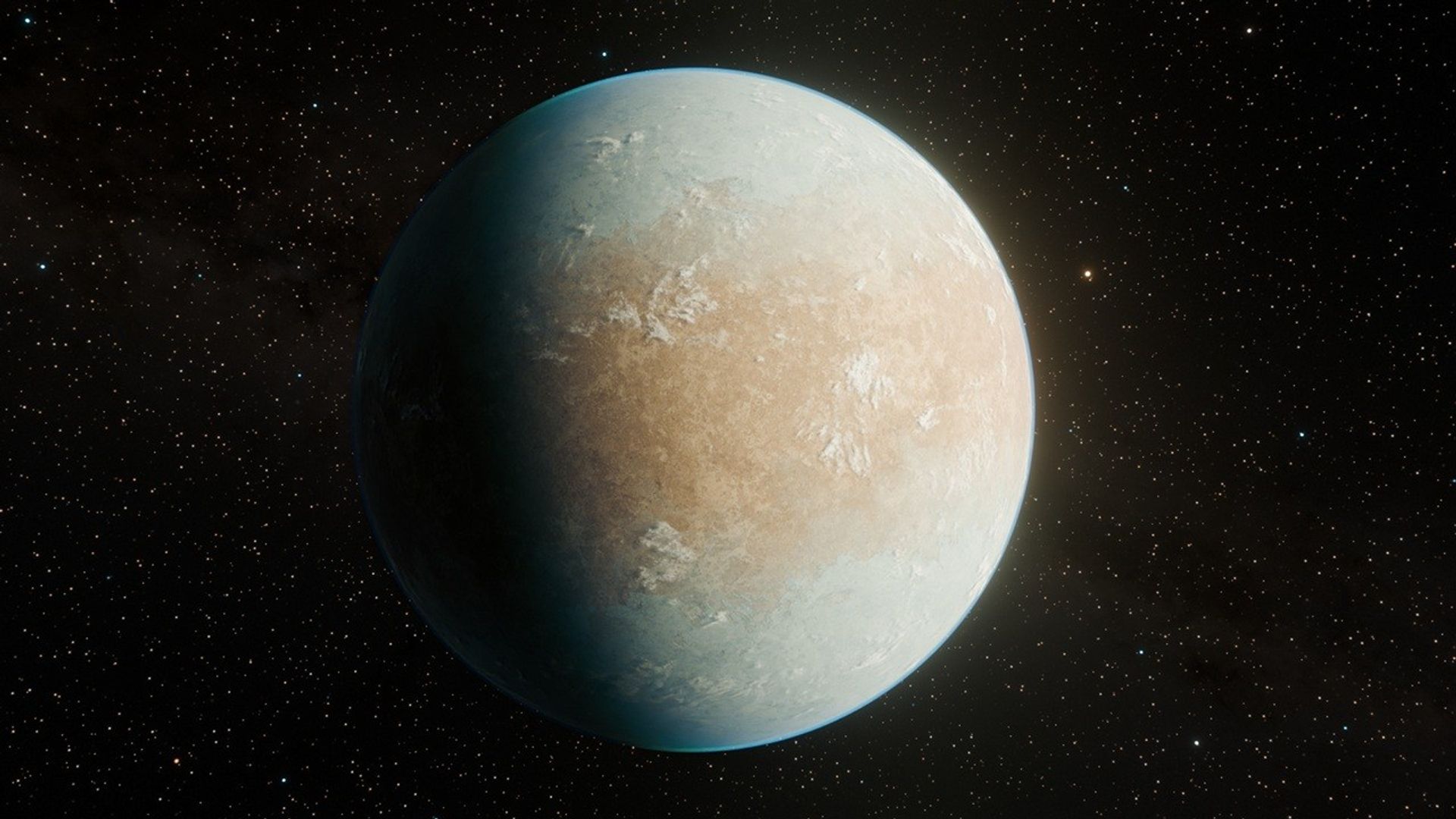

But for TOI 849 b, recently discovered by NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), the price of closeness to its star might have been even higher. Though about the size of Neptune, the planet appears to have little or no atmosphere. Scientists aren't sure why, but the possibilities include photoevaporation – the stripping away of a planet's atmosphere by intense radiation from its star.

Compared to other exoplanets that orbit very close to their stars, this planet is quite unusual because it is 40 times the mass of Earth but only about three times as big around. The gravity of such massive worlds should attract large amounts of gas from the disk of material out of which planets form. And planets with similarly large masses are five to 10 times as wide as Earth. But TOI 849 b is a lot less puffy than that, leading scientists to conclude that it lacks a substantial atmosphere.

The planet's discoverers say TOI 849 b likely was deprived of its atmosphere in one of two ways: Either it was prevented from gathering enough gas for an atmosphere to form in the first place, or that gaseous atmosphere was torn away. Several planet formation scenarios put forth by scientists suggest that such large, remnant cores are unlikely. It might be a relatively rare, very large planet core that somehow survived blasting, baking or having its atmosphere stripped away by such close proximity to the gravitational influence of its star.

The planet might even have lost its atmosphere after colliding with another giant planet.

One more possibility: a bit of bad luck. TOI 849 b might simply have formed inside a gap in the disk of material surrounding the star, depriving it of the chance to cloak itself in atmospheric gases.

TOI 849 b offers tantalizing opportunities to find out just what lurks deep inside gas giants like Jupiter. Future observations could nail down the composition of evaporated material in whatever wisp of an atmosphere might still exist on the planet. That might be something like peeling back Jupiter's gaseous layers and seeing what lies beneath.

This planet also inhabits what astronomers call the "hot Neptunian desert." In this exclusive club, planets in the size-range of Neptune that are super-heated because their orbits are scorchingly close to their stars. It's a "desert" because such objects are spectacularly rare. TOI 849 b is only the second such object to be published in a scientific journal.

A large, international team led by David J. Armstrong of the University of Warwick, United Kingdom, and including NASA scientists, discovered the new planet using TESS, which was launched in 2018. The planet was entered into NASA's Exoplanet Archive on July 9.

Missions like TESS help contribute to the field of astrobiology, the interdisciplinary research on the variables and conditions of distant worlds that could harbor life as we know it.

TESS is a NASA Astrophysics Explorer mission led and operated by MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and managed by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. Additional partners include Northrop Grumman, based in Falls Church, Virginia; NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley; the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts; MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory; and the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. More than a dozen universities, research institutes and observatories worldwide are participants in the mission.