The discovery: Two planets about as massive as Earth orbit a red-dwarf star only 16 light-years away – nearby in astronomical terms. The planets, GJ 1002 b and c, lie within the star’s habitable zone, the orbital distance that could allow liquid water to form on a planet’s surface if it has the right kind of atmosphere.

Key facts: Whether red-dwarf stars are likely to host habitable worlds is a subject of scientific debate. On the minus side, these stars – smaller, cooler, but far longer-lived than stars like our Sun – tend to flare frequently in their youth. Such flares could potentially strip the atmospheres from closely orbiting planets, and the two planets orbiting GJ 1002 are close indeed. Planet b, with a mass slightly higher than Earth’s, is the closer of the two. Its year, once around the star, lasts only 10 days. Planet c, about a third more massive than Earth, takes about 20 days to orbit the star.

On the plus side, however, GJ 1002 seems to be mature enough to have gotten over its youthful tantrums, and now appears quiet. It’s even possible that the early flaring helped build up a variety of molecules on the planets’ surfaces that could be used later, during the star’s quiet period, by any developing life forms that might be present.

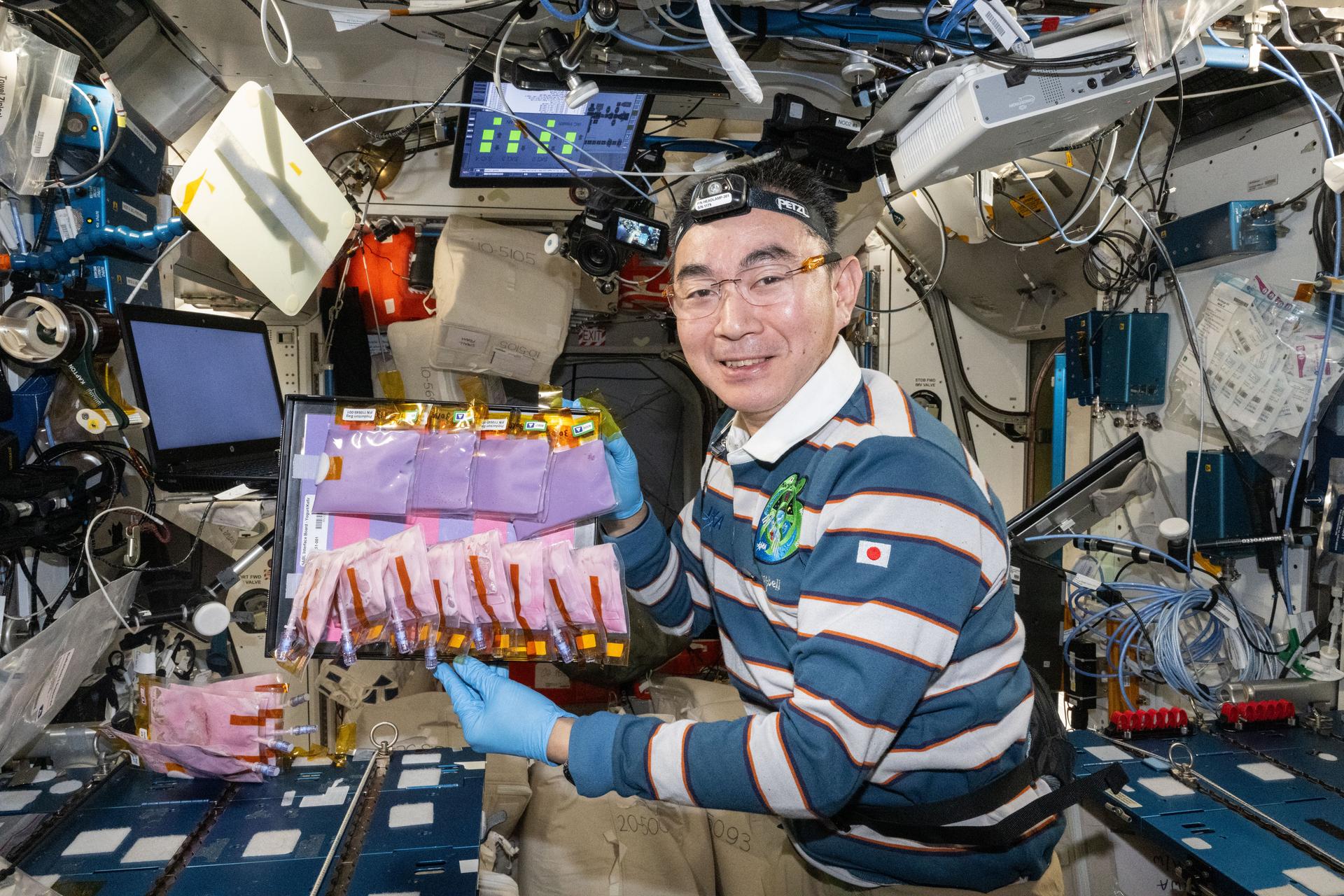

Details: An international team led by Alejandro Suárez Mascareño of the University of La Laguna, Spain, discovered the two new planets using radial velocity measurements – that is, detecting the “wobbles” of the parent star caused by gravitational tugs from orbiting planets. As the planets move toward the far side of the star, they pull the star away from us, causing the star’s light to shift toward the red end of the spectrum. As the planets move toward the star’s near side, they pull the star in our direction, shifting its light toward the blue. The planetary tugs on GJ 1002 are tiny, about 4.3 feet (1.3 meters) per second – equivalent to moving at about 3 miles per hour (4.8 kilometers per hour). Such small movements are difficult to detect.

The radial velocity method, which also reveals how massive the planets are, has yielded more than 1,000 confirmed detections of exoplanets. The most detections, however, have been notched using the “transit” method – watching for a tiny dip in starlight as a planet crosses in front of its star – with nearly 4,000 confirmed detections.

To make its radial velocity measurements, the science team relied on instruments called spectrographs, which measure variations in light. The spectrographs used to discover GJ 1002 b and c were part of two collaborative observation programs: The Echelle SPectrograph for Rocky Exoplanets and Stable Spectroscopic Observations (ESPRESSO), and the Calar Alto high-Resolution search for M-dwarfs with Exoearths with Near-infrared and optical Échelle Spectrographs (CARMENES).

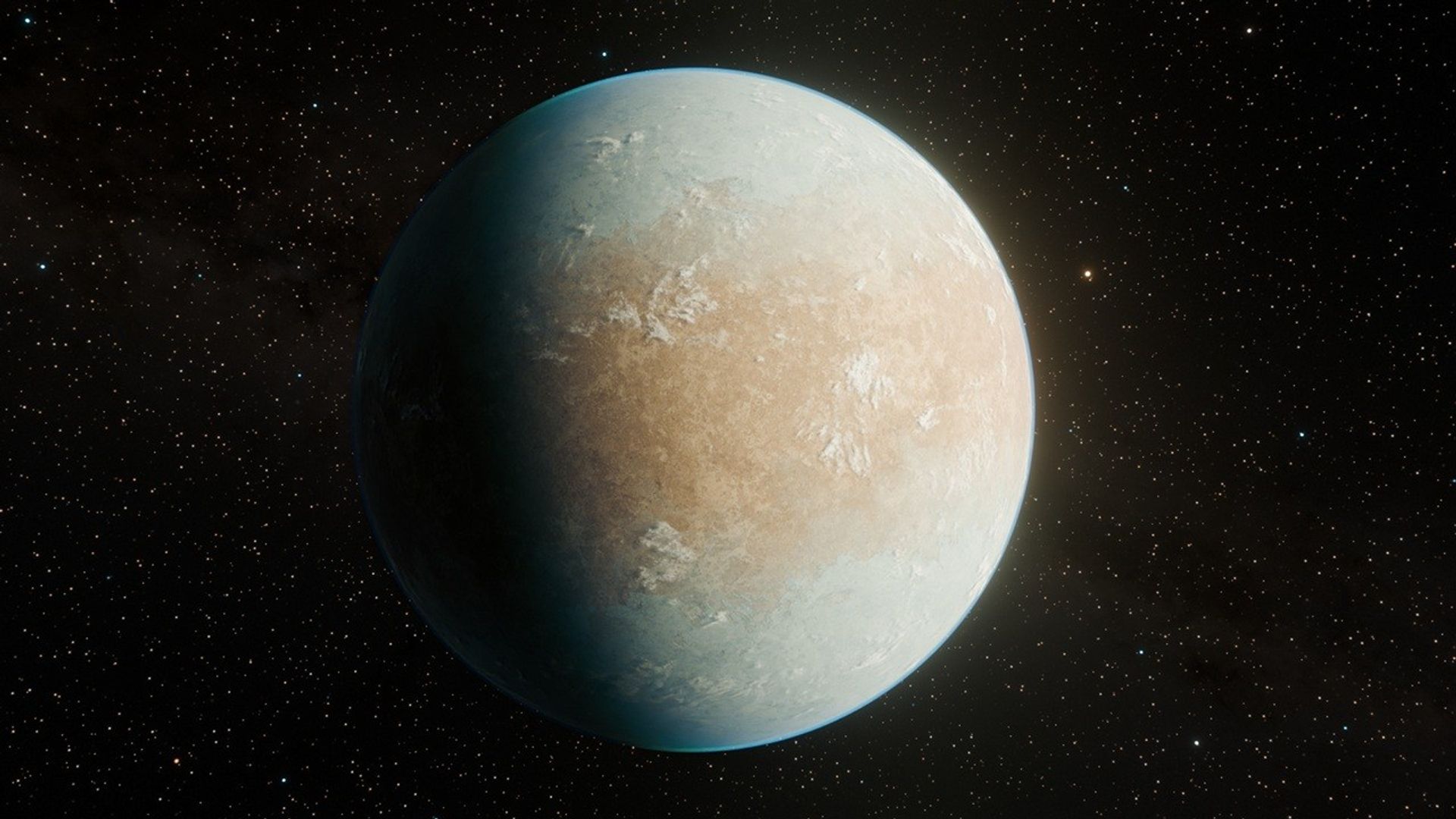

Fun facts: The new planets join 10 others in a fairly exclusive category: small worlds in the “conservative” habitable zone that are less than 1.5 times the size of Earth or less than five times as massive. If we loosen the membership criteria a bit – slightly larger planets in the “optimistic” habitable zone – the group expands to about 40 exoplanets, or planets beyond our solar system. The conservative habitable zone is a stricter boundary for the region around a star that might allow planets to harbor water; optimistic habitable zones expand that boundary a bit. Any habitable zone estimate is a rough approximation. So far, none of these worlds’ atmospheres have been fully analyzed – and many might not possess atmospheres at all.

The discoverers: A paper on the discovery, “Two temperate Earth-mass planets orbiting the nearby star GJ 1002,” by A. Suárez Mascareño and his team, has been accepted for publication in the journal, Astronomy & Astrophysics. The planets were entered into NASA’s Exoplanet Archive on Dec. 22, 2022.