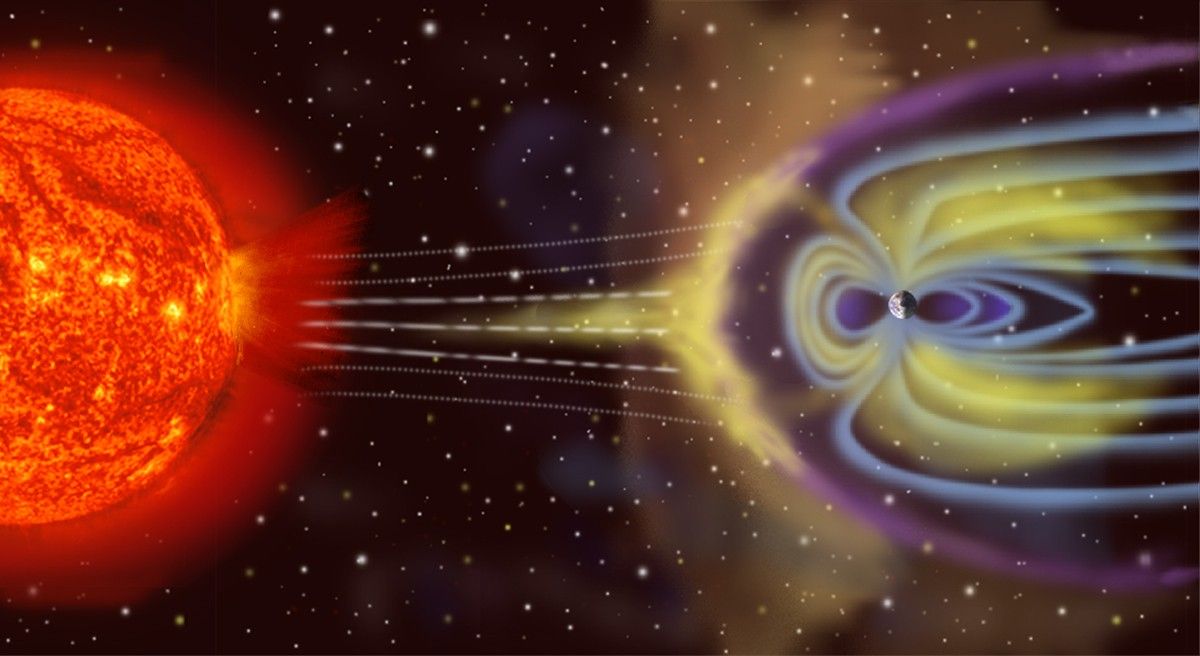

Earth-like planets orbiting close to small stars probably have magnetic fields that protect them from stellar radiation and help maintain surface conditions that could be conducive to life, according to research from astronomers at the University of Washington.

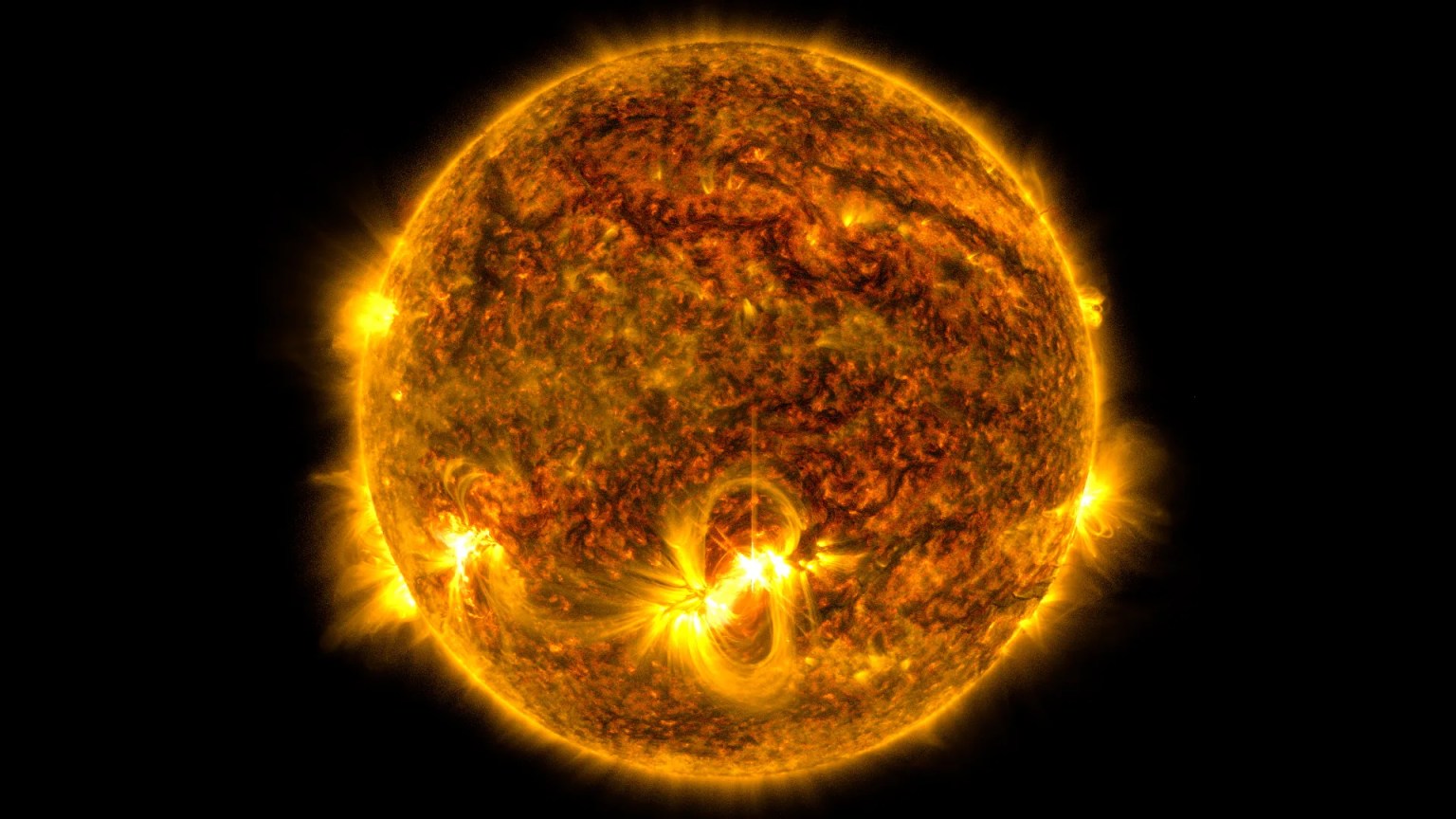

A planet’s magnetic field emanates from its core and is thought to deflect the charged particles of the stellar wind, protecting the atmosphere from being lost to space. Magnetic fields, born from the cooling of a planet’s interior, could also protect life on the surface from harmful radiation as the Earth’s magnetic field protects us.

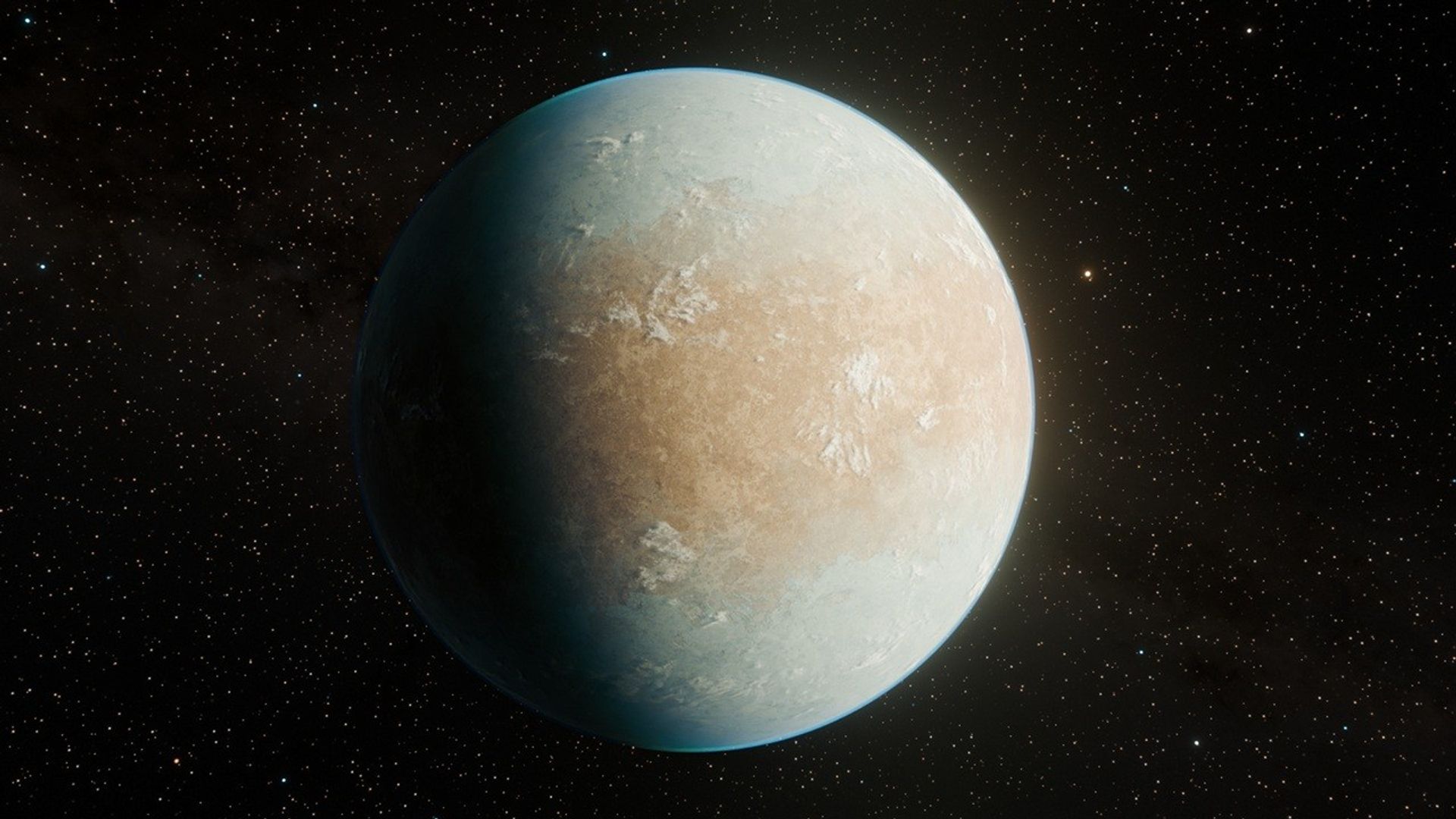

Low-mass stars are among the most common in the universe. Planets orbiting near low-mass stars are easier for astronomers to target for study because when they transit, or pass in front of their host star, they block a larger fraction of the light than if they transited a more massive star. But because such a star is small and dim, its habitable zone — where an orbiting planet gets the heat necessary to maintain life-friendly liquid water on the surface — also lies relatively close in.

And a planet so close to its star is subject to the star’s powerful gravitational pull, which could cause it to become tidally locked, with the same side forever facing its host star, as the moon is with the Earth. That same gravitational tug from the star also creates tidally-generated heat inside the planet, or tidal heating. Tidal heating is responsible for driving the most volcanically active body in our solar system, Jupiter’s moon Io.

A tidally locked planet orbits its star with only one side facing the star, much like the moon orbits Earth (left). A planet like Earth gets starlight on both its near and far sides (right).

In a paper published Sept. 22 in the journal Astrobiology, lead author Peter Driscoll sought to determine the fate of such worlds across time: “The question I wanted to ask is, around these small stars where people are going to look for planets, are these planets going to be roasted by gravitational tides?” He was curious too about the effect of tidal heating on magnetic fields across long periods of time.

The research combined models of orbital interactions and heating by Rory Barnes, assistant professor of astronomy, with those of thermal evolution of planetary interiors done by Driscoll, who began this work as a UW postdoctoral fellow and is now a geophysicist at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C.

Their simulations ranged from one stellar mass — stars the size of our sun — down to about one-tenth of that size. By merging their models they were able, Barnes said, “to produce a more realistic picture of what is happening inside these planets.”

Barnes said there has been a general feeling in the astronomical community that tidally locked planets are unlikely to have protective magnetic fields “and therefore are completely at the mercy of their star.” This research suggests that assumption is false.

Far from being harmful to a planet’s magnetic field, tidal heating can actually help it along — and in doing so also help the chance for habitability.

This is because of the somewhat counterintuitive fact that the more tidal heating a planetary mantle experiences, the better it is at dissipating its heat, thereby cooling the core, which in turn helps create the magnetic field.

Barnes said that in computer simulations they were able to generate magnetic fields for the lifetimes of these planets, in most cases. “I was excited to see that tidal heating can actually save a planet in the sense that it allows cooling of the core. That’s the dominant way to form magnetic fields.”

And since small or low mass stars are particularly active early in their lives — for the first few billion years or so — “magnetic fields can exist precisely when life needs them the most.”

Driscoll and Barnes also found through orbital calculations that the tidal heating process is more extreme for planets in the habitable zone around very small stars, or those less than half the mass of the sun.

For planets in eccentric, or noncircular, orbits around such low mass stars, they found that these orbits tend to become more circular during the time of extreme tidal heating. Once that circularization takes place, the planet stops experiencing any tidal heating at all.

The research was done through the Virtual Planetary Laboratory, a UW-based interdisciplinary research group funded through the NASA Astrobiology Institute.

“These preliminary results are promising, but we still don’t know how they would change for a planet like Venus, where slow planetary cooling is already hindering magnetic field generation,” Driscoll said. “In the future, exoplanetary magnetic fields could be observable, so we expect there to be a growing interest in this field going forward.”