By Pat Brennan

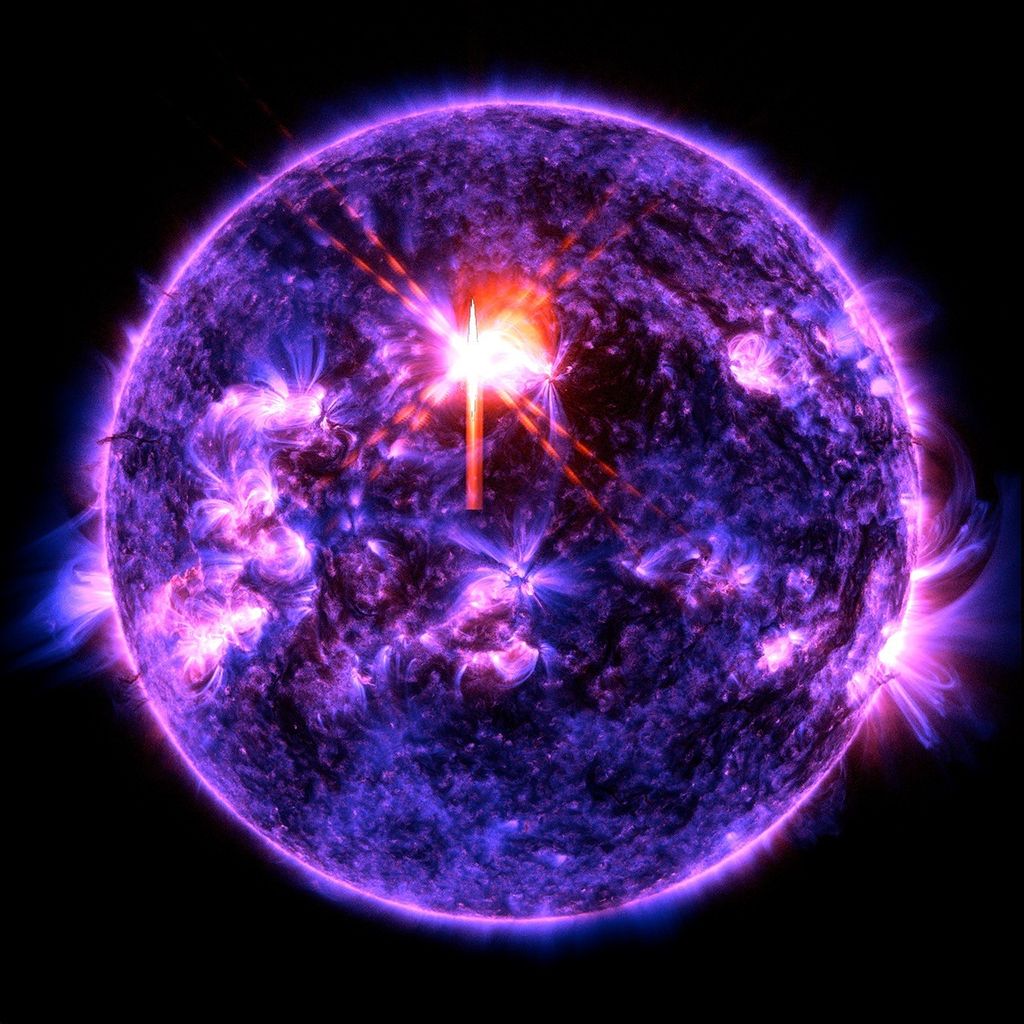

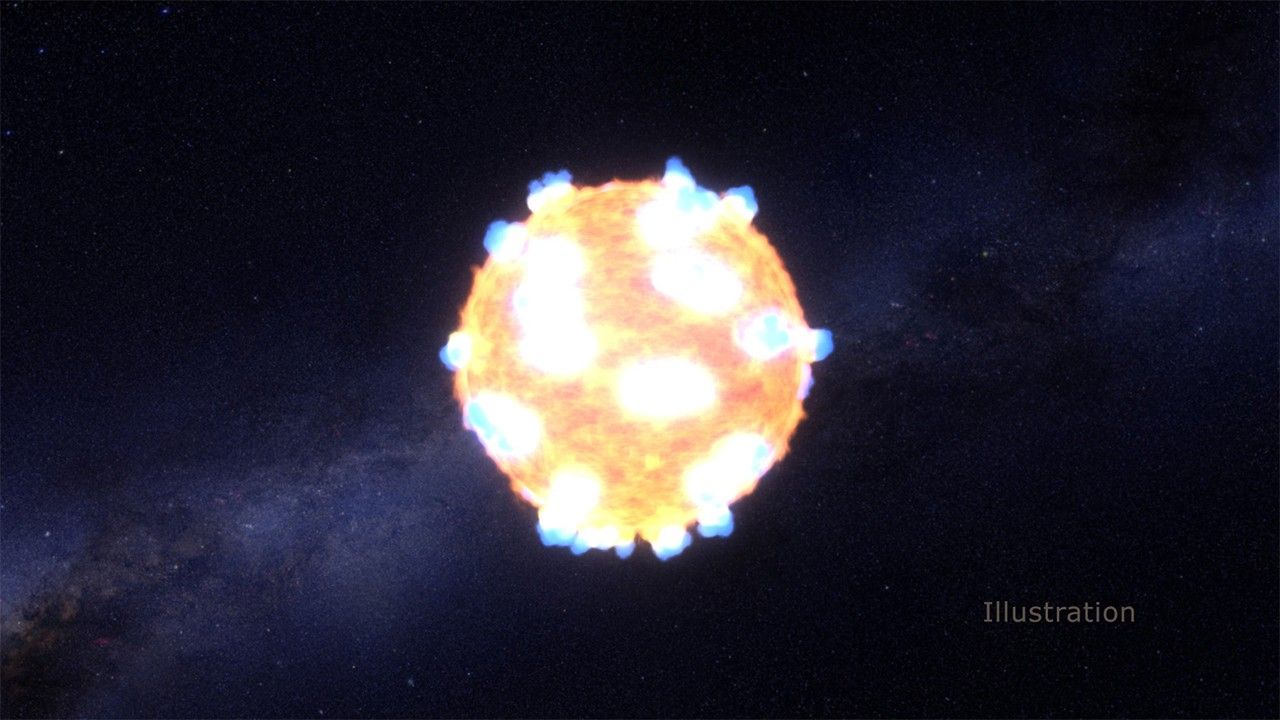

The brilliant flash of an exploding star's shockwave – what astronomers call the "shock breakout"– has been captured for the first time in visible light by NASA's planet-hunter, the Kepler space telescope.

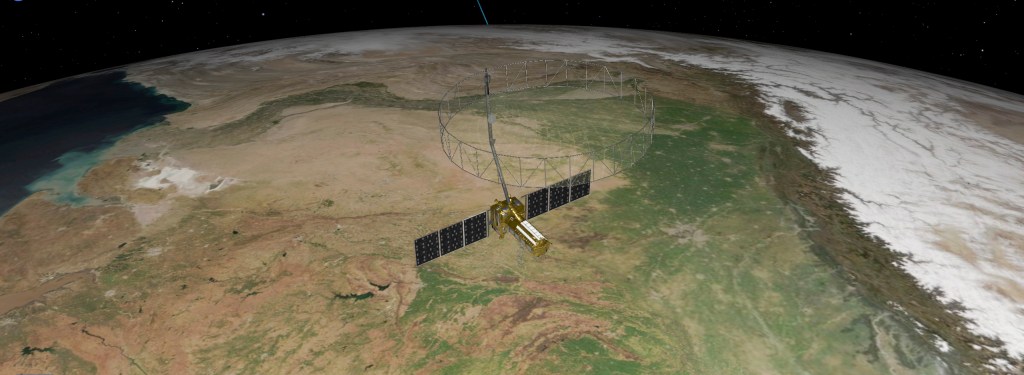

An international science team led by Peter Garnavich, an astrophysics professor at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, analyzed light captured by Kepler every 30 minutes over a three-year period from 500 distant galaxies, searching some 50 trillion stars. They were hunting for signs of massive stellar death explosions known as supernovae.

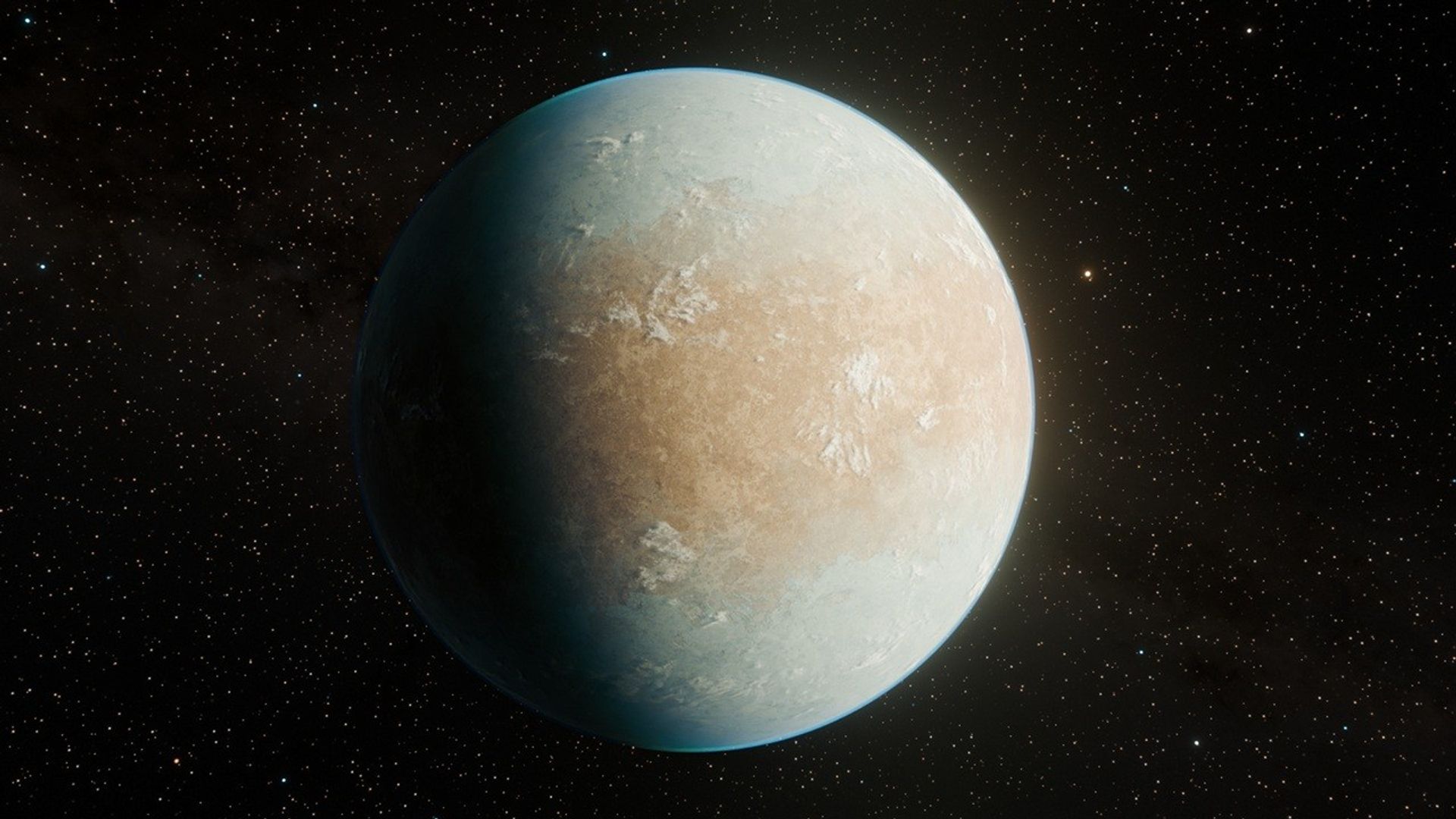

In 2011, two of these massive stars, called red supergiants, exploded while in Kepler's view. The first behemoth, KSN 2011a, is nearly 300 times the size of our sun and a mere 700 million light-years from Earth. The second, KSN 2011d, is roughly 500 times the size of our sun and around 1.2 billion light-years away.

"To put their size into perspective, Earth's orbit about our sun would fit comfortably within these colossal stars," said Garnavich.

Whether it's a plane crash, car wreck or supernova, capturing images of sudden, catastrophic events is extremely difficult but tremendously helpful in understanding root causes. Just as widespread deployment of mobile cameras has made forensic videos more common, the steady gaze of Kepler allowed astronomers to see, at last, a supernova shockwave as it reached the surface of a star. The shock breakout itself lasts only about 20 minutes, so catching the flash of energy is an investigative milestone for astronomers.

NASA Ames, STScI/G. Bacon

"In order to see something that happens on timescales of minutes, like a shock breakout, you want to have a camera continuously monitoring the sky," said Garnavich. "You don't know when a supernova is going to go off, and Kepler's vigilance allowed us to be a witness as the explosion began."

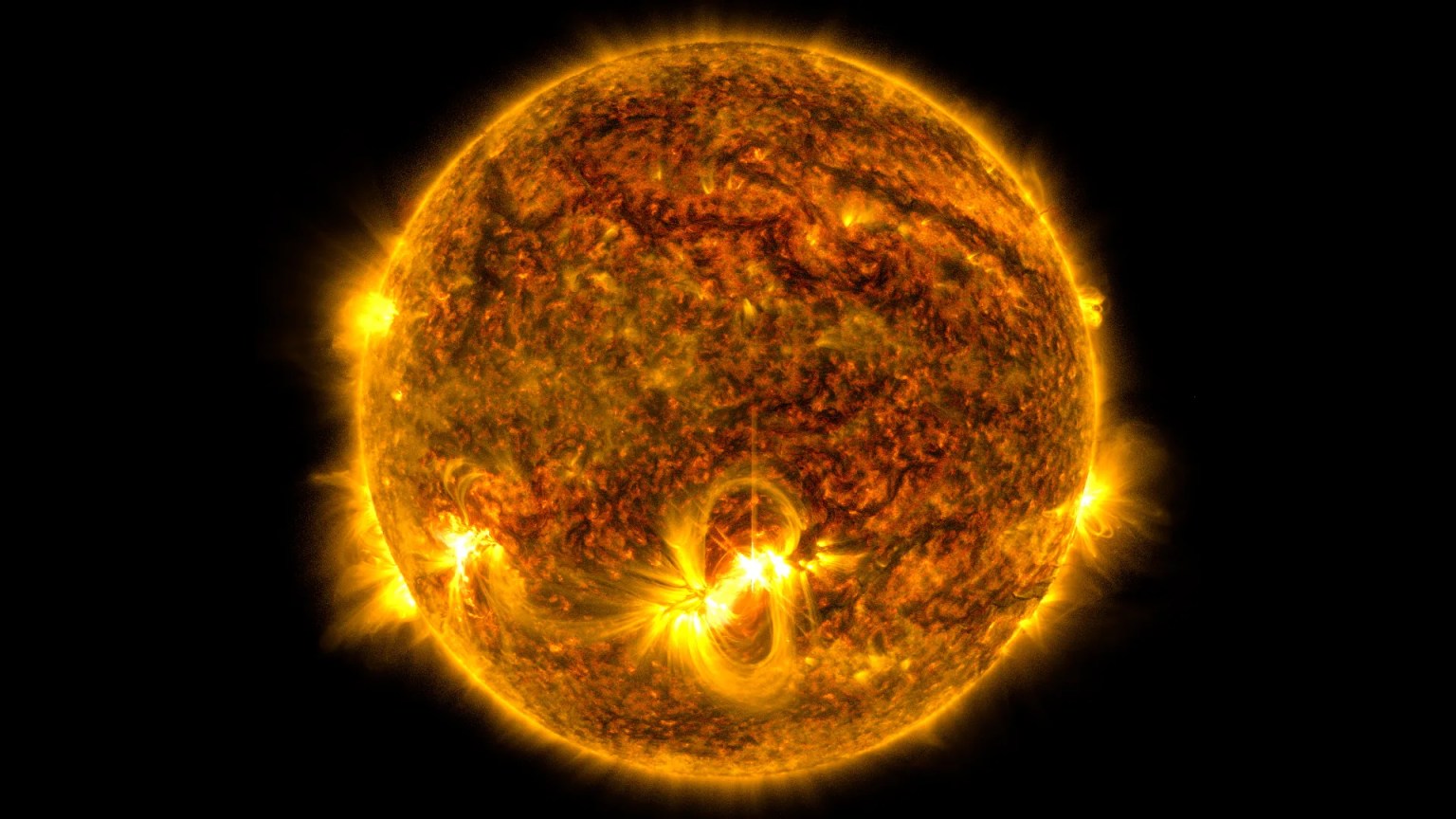

Supernovae like these – known as Type II – begin when the internal furnace of a star runs out of nuclear fuel, causing its core to collapse as gravity takes over.

The two supernovae matched up well with mathematical models of Type II explosions reinforcing existing theories. But they also revealed what could turn out to be an unexpected variety in the individual details of these cataclysmic stellar events.

While both explosions delivered a similar energetic punch, no shock breakout was seen in the smaller of the supergiants. Scientists think that is likely due to the smaller star being surrounded by gas, perhaps enough to mask the shockwave when it reached the star's surface.

"That is the puzzle of these results," said Garnavich. "You look at two supernovae and see two different things. That's maximum diversity."

Understanding the physics of these violent events allows scientists to better understand how the seeds of chemical complexity and life itself have been scattered in space and time in our Milky Way galaxy.

"All heavy elements in the universe come from supernova explosions. For example, all the silver, nickel, and copper in the earth and even in our bodies came from the explosive death throes of stars," said Steve Howell, project scientist for NASA's Kepler and K2 missions at NASA's Ames Research Center in California's Silicon Valley. "Life exists because of supernovae."

Garnavich is part of a research team known as the Kepler Extragalactic Survey or KEGS. The team is nearly finished mining data from Kepler's primary mission, which ended in 2013 with the failure of reaction wheels that helped keep the spacecraft steady. However, with the reboot of the Kepler spacecraft as NASA's K2 mission, the team is now combing through more data hunting for supernova events in even more galaxies far, far away.

"While Kepler cracked the door open on observing the development of these spectacular events, K2 will push it wide open, observing dozens more supernovae," said Tom Barclay, senior research scientist and director of the Kepler and K2 guest observer office at Ames. "These results are a tantalizing preamble to what's to come from K2!"

In addition to Notre Dame, the KEGS team also includes researchers from the University of Maryland in College Park; the Australian National University in Canberra, Australia; the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland; and the University of California, Berkeley.

The research paper reporting this discovery has been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal.

For more information about the Kepler and K2 missions, visit:

Media contact:

Michele Johnson

Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, Calif.

650-604-6982

michele.johnson@nasa.gov