3 min read

By Joshua Rodriguez

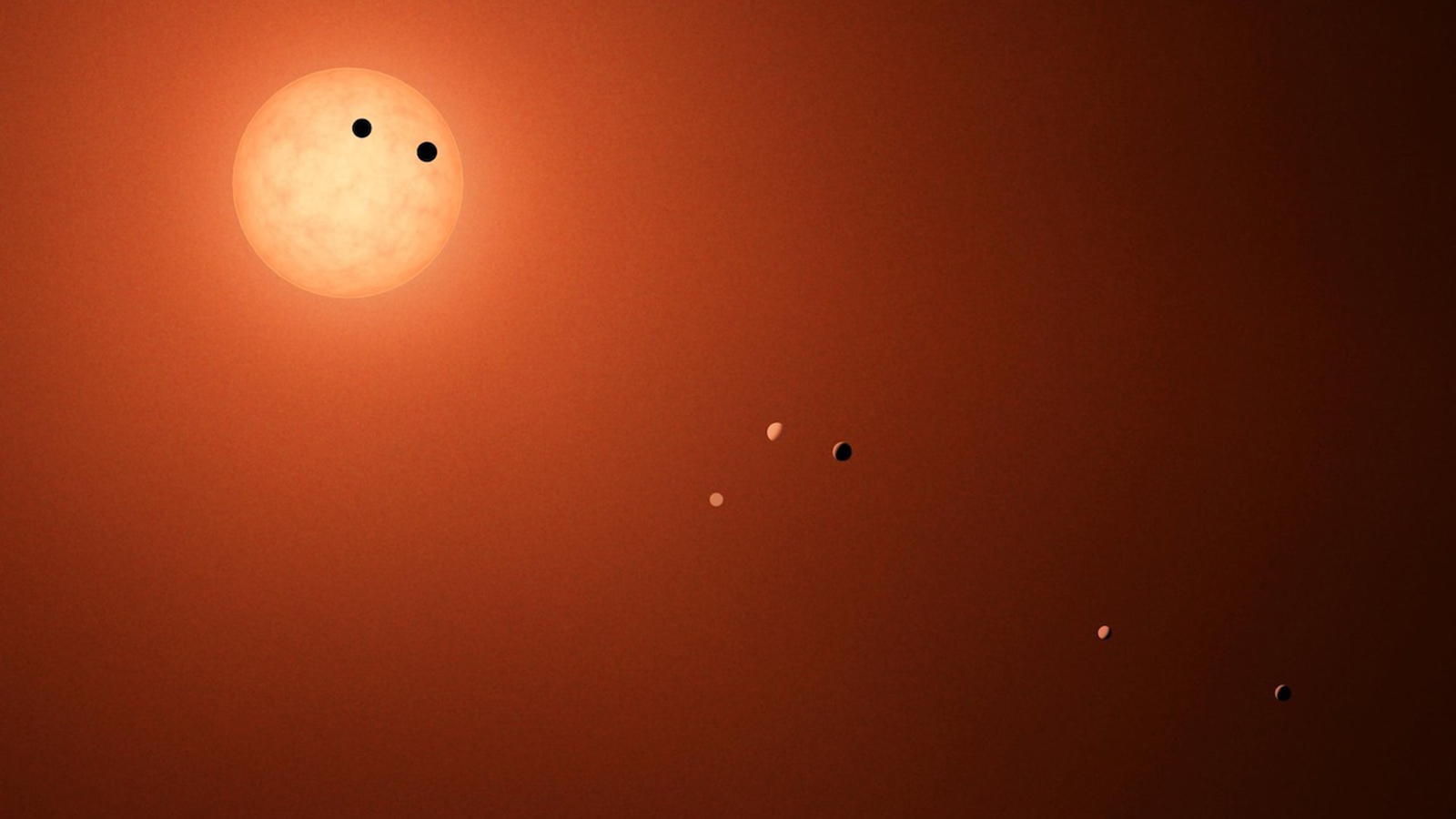

When astronomers in the 1990s first started discovering massive, Jupiter-size worlds whipping around their stars in a matter of mere days, the rulebook for what kinds of planets were and weren’t possible had to be tossed out the window.

Now, thanks to data from the ever-prolific Kepler mission, an even more extreme class of exoplanets is causing scientists to once again redefine the rules.

When Carnegie Institution of Washington astronomer Brian Jackson and his team set out to find extremely close-orbiting exoplanets in Kepler’s treasure trove of data, he wasn’t optimistic that they’d find anything. “Most of the time, things like this don’t work out,” he said.

But his team hit pay dirt when they found strong evidence for planets with orbits of as little as three hours—the first such transiting planet ever discovered.

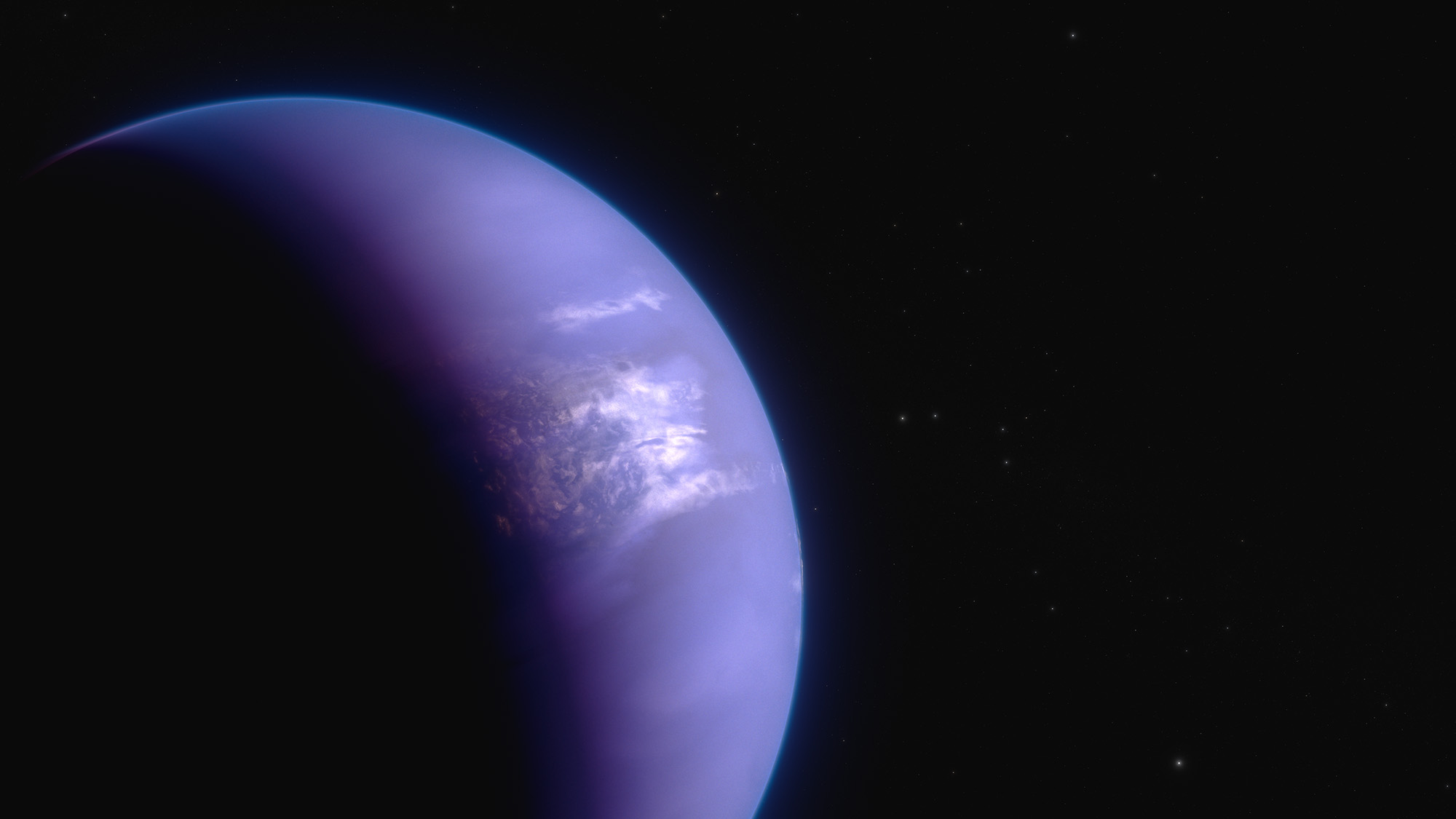

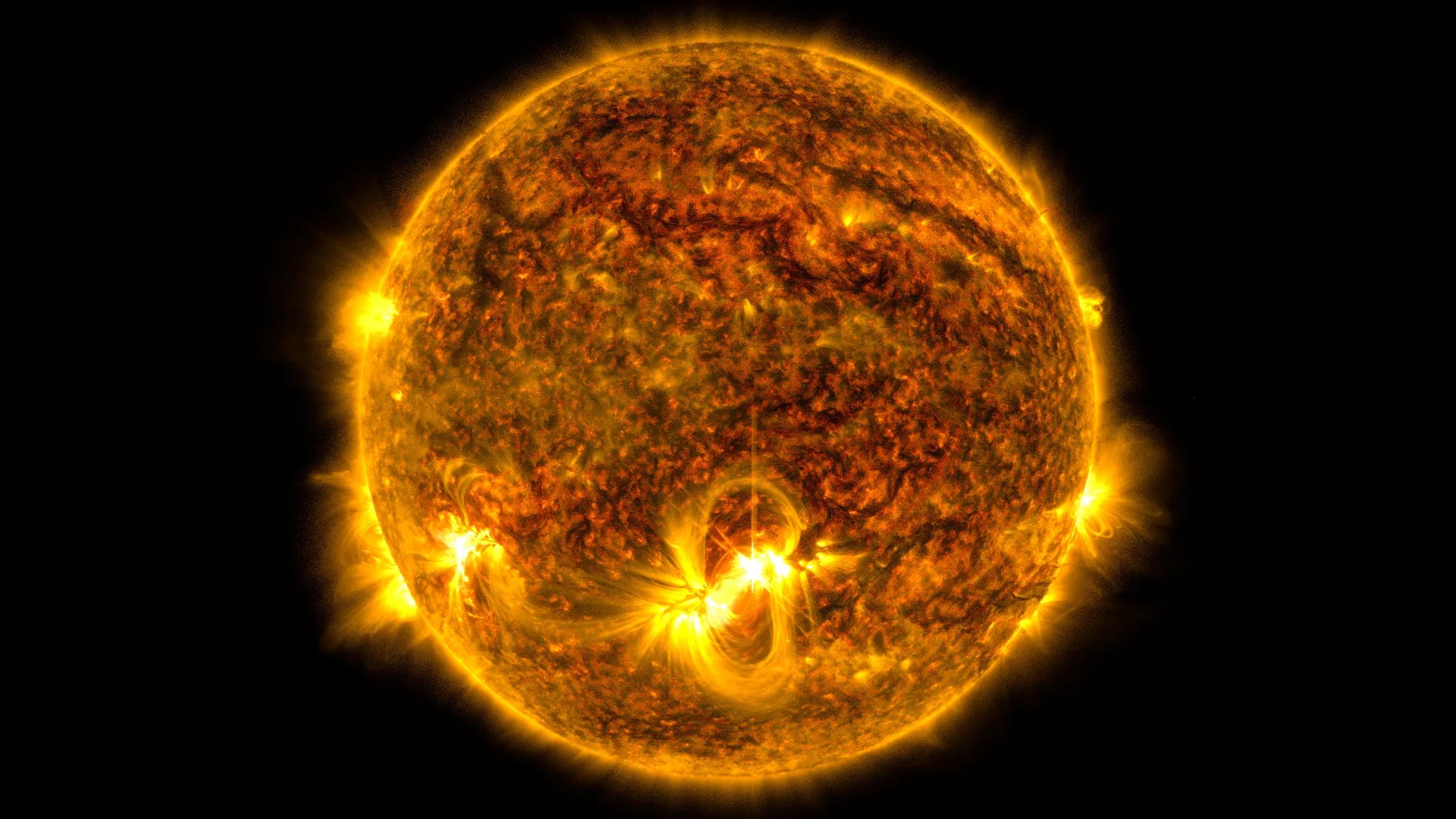

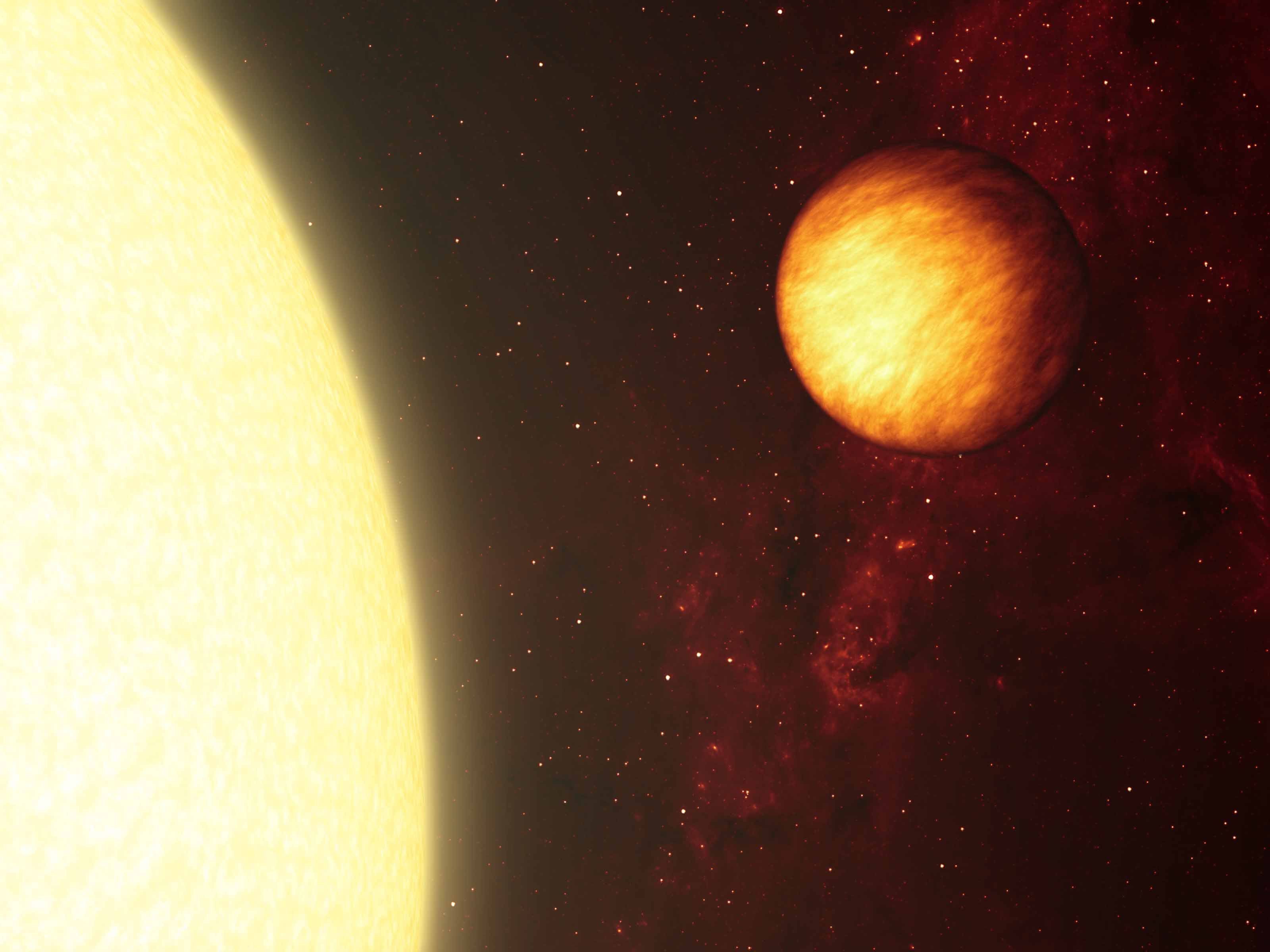

“These planets are nearly skimming the stellar surface, and if they’re confirmed, they’ll be some of the closest planets to their stars ever discovered,” Jackson said.

“The results were very surprising,” Jackson said. “The first hot Jupiters, with their several-day orbits, were completely unexpected, but these planets are even closer—almost touching the star itself.”

The discovery of such extreme worlds prompts new questions about how such a planet could form in the first place.

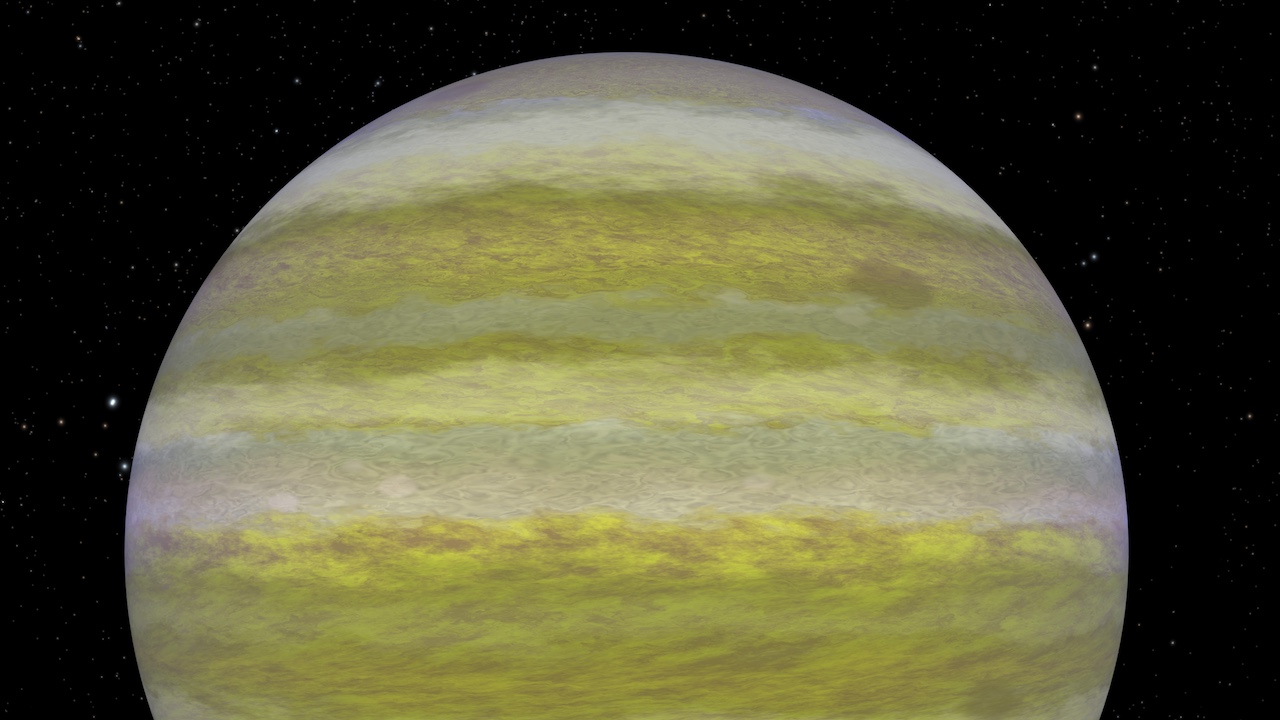

“They could be the carcasses of former gas giants that have had their atmospheres entirely ripped off by the gravity of their star, leaving behind an Earth-size solid core of ice and rock,” Jackson said. “But the reality is that at present, we don’t know where they came from.”

And just how long can a planet survive at such an incredibly cozy distance from its host star? “We know they have to survive long enough for us to see them,” Jackson said. “But at the same time, this is something that’s orbiting 50 times closer to its star than Mercury is to the sun ... it’s practically skimming the star's surface.”

Jackson and his team now turn to gathering the information needed to understand this enigmatic new class of planets. “We want to find some more, and view them closer with high-powered ground instruments so that we can try to understand them theoretically,” Jackson said.

“This discovery pushes the envelope even further,” Jackson said. “Now we’ve got to explain these amazing new planets.”

While Jackson is “surprised and gratified” by his team’s groundbreaking new find, he recognizes that the exoplanet field has a habit of confounding expectations. “It’s a huge challenge, understanding the vast menagerie of planets that are out there,” he said.

“Every time astronomers think we have a handle on where planets can and can’t live, nature surprises us.”