4 min read

◆ Three 'Tatooine'-like planets have been discovered orbiting two Sun-like stars.

◆ The planets are large like Jupiter, and may help scientists learn why our solar system is different from others found in the galaxy.

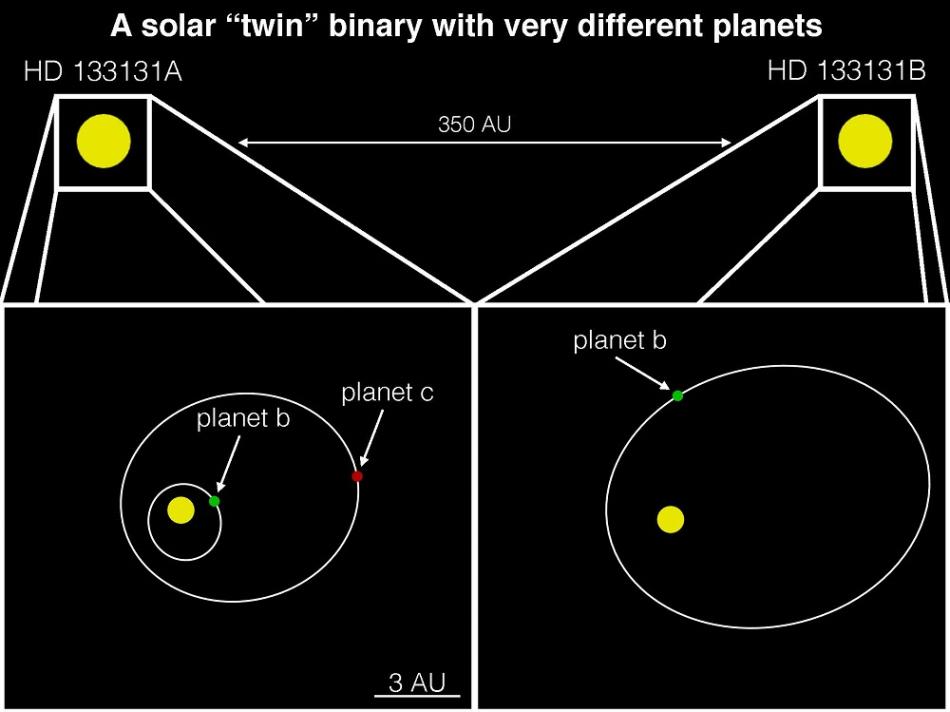

A team of Carnegie scientists has discovered three giant planets in a binary star system composed of stellar ''twins'' that are also effectively siblings of our sun. One star hosts two planets and the other hosts the third. The system represents the smallest-separation binary in which both stars host planets that has ever been observed. The findings, which may help explain the influence that giant planets like Jupiter have over a solar system’s architecture, have been accepted for publication in The Astronomical Journal.

New discoveries coming from the study of exoplanetary systems will show us where on the continuum of ordinary to unique our own solar system’s layout falls. So far, planet hunters have revealed populations of planets that are very different from what we see in our solar system. The most-common exoplanets detected are so-called super-Earths, which are larger than our planet but smaller than Neptune or Uranus. Given current statistics, Jupiter-sized planets seem fairly rare—having been detected only around a small percentage of stars.

This is of interest because Jupiter’s gravitational pull was likely a huge influence on our solar system’s architecture during its formative period. So the scarcity of Jupiter-like planets could explain why our home system is different from all the others found to date.

The new discovery from the Carnegie team is the first exoplanet detection made based solely on data from the Planet Finder Spectrograph—developed by Carnegie scientists and mounted on the Magellan Clay Telescopes at Carnegie’s Las Campanas Observatory. PFS is able to find large planets with long-duration orbits or orbits that are very elliptical rather than circular, including the new trio of planets discovered in this `”twin’” star study. This special capability comes from the long observing baseline of PFS; it has been taking observations for six years.

Led by Johanna Teske, the team included a number of Carnegie scientists from both the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism in Washington, DC, and the Carnegie Observatories in Pasadena, CA, as well as Steve Vogt of the University of California Santa Cruz.

“We are trying to figure out if giant planets like Jupiter often have long and, or eccentric orbits,” Teske explained. “If this is the case, it would be an important clue to figuring out the process by which our solar system formed, and might help us understand where habitable planets are likely to be found.”

The twin stars studied by the group are called HD 133131A and HD 133131B. The former hosts two moderately eccentric planets, one of which is, at a minimum, about 1.5 times Jupiter’s mass and the other of which is, at a minimum, just over half Jupiter’s mass. The latter hosts one moderately eccentric planet with a mass at least 2.5 times Jupiter’s.

The two stars themselves are separated by only 360 astronomical units (AU). One AU is the distance between the Earth and the sun. This is extremely close for twin stars with detected planets orbiting the individual stars. The next-closest binary system that hosts planets is comprised of two stars that are about 1,000 AU apart.

The system is even more unusual because both stars are “metal poor,” meaning that most of their mass is hydrogen and helium, as opposed to other elements like iron or oxygen. Most stars that host giant planets are "metal rich.” Only six other metal-poor binary star systems with exoplanets have ever been found, making this discovery especially intriguing.

Adding to the intrigue, Teske used very precise analysis to reveal that the stars are not actually identical “twins” as previously thought, but have slightly different chemical compositions, making them more like the stellar equivalent of fraternal twins.

This could indicate that one star swallowed some baby planets early in its life, changing its composition slightly. Alternatively, the gravitational forces of the detected giant planets that remained may have had a strong effect on fully-formed small planets, flinging them in towards the star or out into space.

“The probability of finding a system with all these components was extremely small, so these results will serve as an important benchmark for understanding planet formation, especially in binary systems,” Teske explained.

The other members of Teske’s team were Carnegie’s Stephen Shectman, Matías Díaz, Paul Butler, Jeffrey Crane, and Pamela Arriagada.