Wildfires and

Climate Change

Earth's warming climate is amplifying wildland fire activity, particularly in northern and temperate forests. When fires ignite the landscape, NASA’s satellites and instruments can detect and track them. This information helps communities and land managers around the world prepare for and respond to fires, and also provides a rich data source to help scientists better understand this growing risk.

-

Extreme wildfire activity has more than doubled worldwide.

NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites detect active wildfires twice each day. Scientists studied this data over a 21-year span and found that extreme wildfires have become more frequent, more intense, and larger. The largest increase in extreme fire behavior was in the temperate conifer forests of the Western U.S. and the boreal forests of northern North America and Russia. Warmer nighttime temperatures are a major contributing factor, allowing fire activity to persist overnight.

See the research - Increasing frequency and intensity of the most extreme wildfires on Earth

Rapid growth of wildfires over an 8-day period in Quebec, Canada in June, 2023. This animation was made using satellite detections of active fires and hotspots, displayed in NASA’s FIRMS tool.Credit: NASA

Rapid growth of wildfires over an 8-day period in Quebec, Canada in June, 2023. This animation was made using satellite detections of active fires and hotspots, displayed in NASA’s FIRMS tool.Credit: NASA -

Fire season is getting longer, and emissions larger.

In 2021, a destructive wintertime wildfire in Colorado became part of a growing trend of wildfire activity extending well beyond the summer. By looking back at 35 years of weather data, U.S. Forest Service scientists found that fire seasons are starting earlier in the spring and extending later into autumn. Parts of the Western United States, Mexico, Brazil, and East Africa now have fire seasons that are more than a month longer than they were 35 years ago.

Wildfires also can be a major source of carbon dioxide emissions. Researchers found that carbon emissions from forest fires increased by 60% globally between 2001 and 2023. Fire emissions from boreal forests in Eurasia and North America nearly tripled during that same time period, driven by a warmer, drier climate.

In 2023, Canada’s warmest and driest conditions since 1980 stoked extreme fires that lasted for five months. NASA researchers found that these fires released about 640 million metric tons of carbon.

See the research:

- Fire seasons getting longer, more frequent

- Global rise in forest fire emissions linked to climate change in the extratropicsNASA Study Tallies Carbon Emissions from Massive Canadian Fires

Carbon monoxide (CO) emissions from wildfires in Canada during early June, 2023. Red triangles are fire hotspots. See an animation of this data.Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center -

Fire weather is becoming more common, and human activities are the main cause.

Although some variations in the weather are natural, human-caused climate change has been found to be the main cause for increasing fire weather in the American West.

As the planet warms, hotter weather, earlier melting of winter snow, warmer nighttime temperatures, and decreasing summer rainfall are all contributing to increased fire activity. In the Western U.S., the amount of summertime precipitation has the biggest effect on how much land area is burned in a given year. Historical efforts to reduce all wildfires led to decades of fire suppression, which has caused a buildup of fuels in some forests. This combination of fuel build-up and warmer, drier conditions increases the potential for extreme fires.

See the research:

- Decreasing fire season precipitation increased recent western U.S. forest wildfire activity

- Quantifying contributions of natural variability and anthropogenic forcings on increased fire weather risk over the Western United States

Smoke along Monroe Mountain during a prescribed fire conducted in Utah's Fishlake National Forest during USFS FASMEE 2023 campaign.Credit: Grace Weikert / NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Smoke along Monroe Mountain during a prescribed fire conducted in Utah's Fishlake National Forest during USFS FASMEE 2023 campaign.Credit: Grace Weikert / NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Wildfires: a natural process supercharged by humans.

Fire is a natural part of many landscapes, and sometimes it is beneficial to forests and grassland ecosystems that have evolved with fire. Many different factors influence wildfire behavior, such as forest health, weather, topography, and forest management practices. A warming climate is increasing some types of fire activity, leading to larger and more destructive fires, more intensive firefighting efforts, and widespread smoke

-

Wildfires in the U.S. have been getting larger.

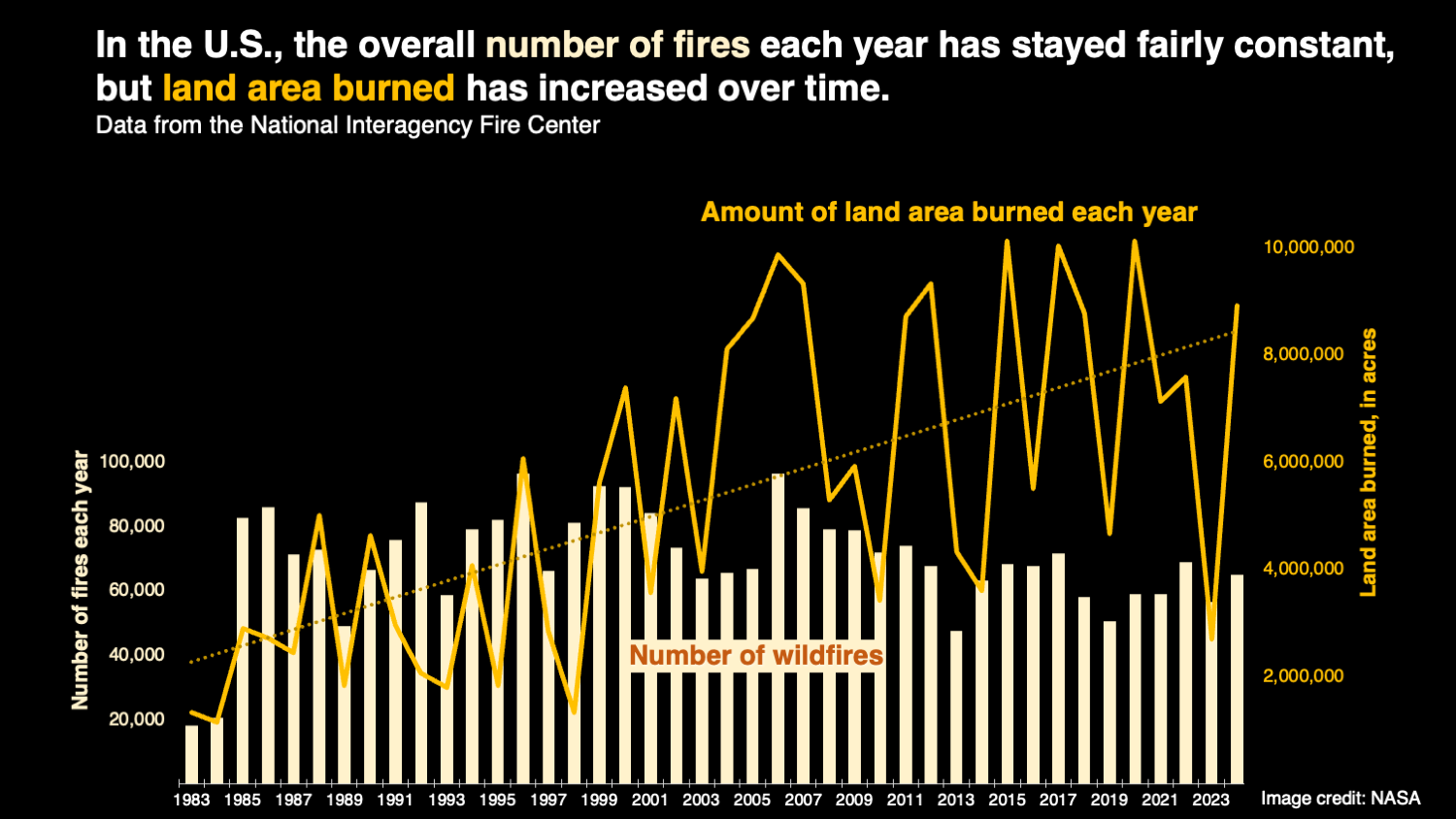

The size and number of wildfires in the United States has been recorded since 1983 by the National Interagency Fire Center. Over the past 20 years, the amount of land area burned each year has increased as wildfires have grown larger, while the number of fires each year has remained fairly constant.

See the data from the National Interagency Fire Center (current through 2023)

This graph shows the number of wildfires and the amount of land area burned by wildfires in the U.S. every year from 1983 through 2024. The amount of land area burned each year has increased as wildfires have grown larger, while the number of fires each year has remained fairly constant. Data from the National Interagency Fire Center.Credit: NASA

This graph shows the number of wildfires and the amount of land area burned by wildfires in the U.S. every year from 1983 through 2024. The amount of land area burned each year has increased as wildfires have grown larger, while the number of fires each year has remained fairly constant. Data from the National Interagency Fire Center.Credit: NASA -

Some types of fires are decreasing.

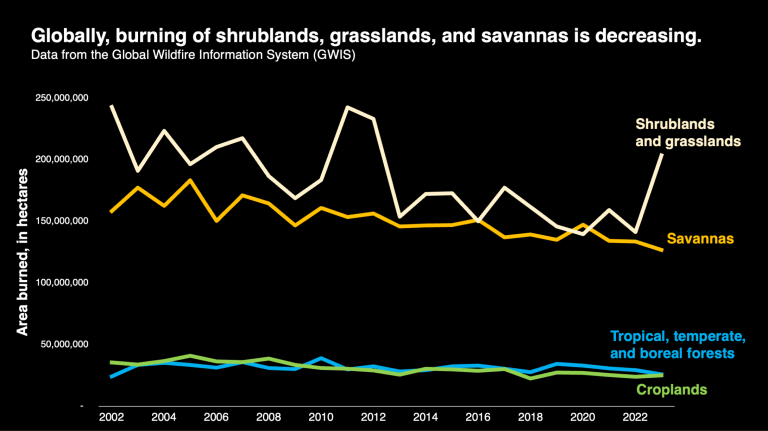

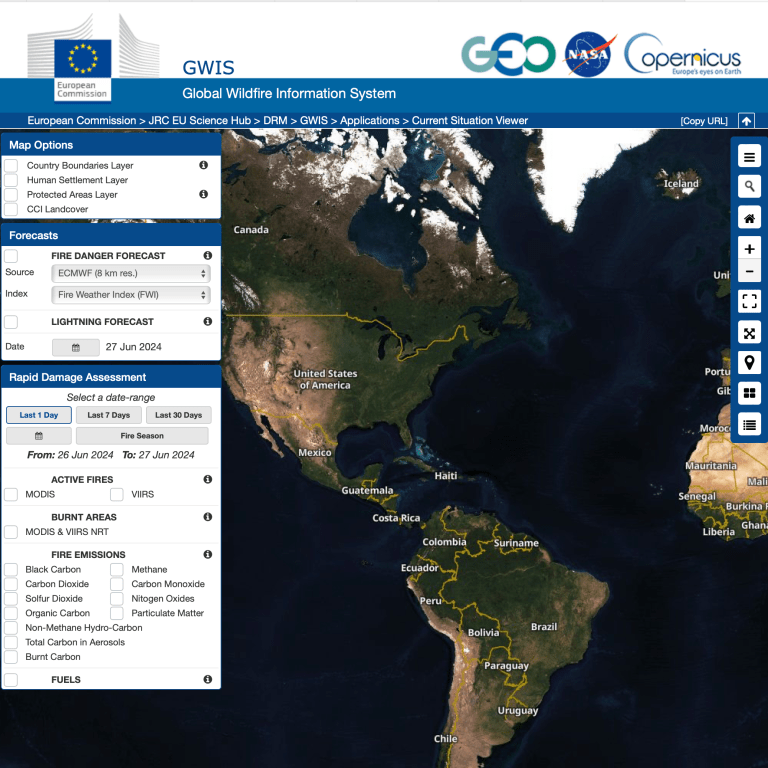

Fires are part of both natural processes and human land use practices. Our ability to understand fire activity in different parts of the world is strengthened by international collaborations such as the Global Wildfire Information System, which includes data from NASA satellites.

For example, Indigenous and nomadic cultures have historically relied on fire as a tool to clear land, keep shrubs from encroaching into grazing areas, and maintain healthy ecosystems. Periodic fires have played a role in stewarding savanna and grassland habitats for thousands of years. In some regions, fires are commonly used to clear crop residue and prepare land for new plantings. Over time, humans have gradually shifted away from nomadic life toward building homes, roads, and farms in permanent locations. These changes in cultural practices have reduced the use of fire as a land management tool. Global fire data shows that the total amount of land burned each year is decreasing, particularly in shrublands, grasslands, and savannas. The use of fire as a tool to manage cropland has declined over the past 20 years, leading to a reduction of the area burned by fires in shrubland, grassland, and savanna landscapes. Data from the Global Wildfire Information System (GWIS).Credit: NASA

The use of fire as a tool to manage cropland has declined over the past 20 years, leading to a reduction of the area burned by fires in shrubland, grassland, and savanna landscapes. Data from the Global Wildfire Information System (GWIS).Credit: NASA

NASA offers real-time wildfire monitoring tools.

-

NASA’s Fire Information for Resource Management System (FIRMS) mapping tool offers near-real time fire data. The tool can be used in basic mode to look at active fires, daily mapping of burned areas, aerosol plumes, and more. Click on advanced mode to see details of aerosol plumes, burned area from past fires, and fire weather hazards. There are two versions of the tool: one for the U.S. and Canada, and one for global fires.

Screen recording of how to use FIRMS to zoom in on an active fire, see the burned area outline, and get more information. -

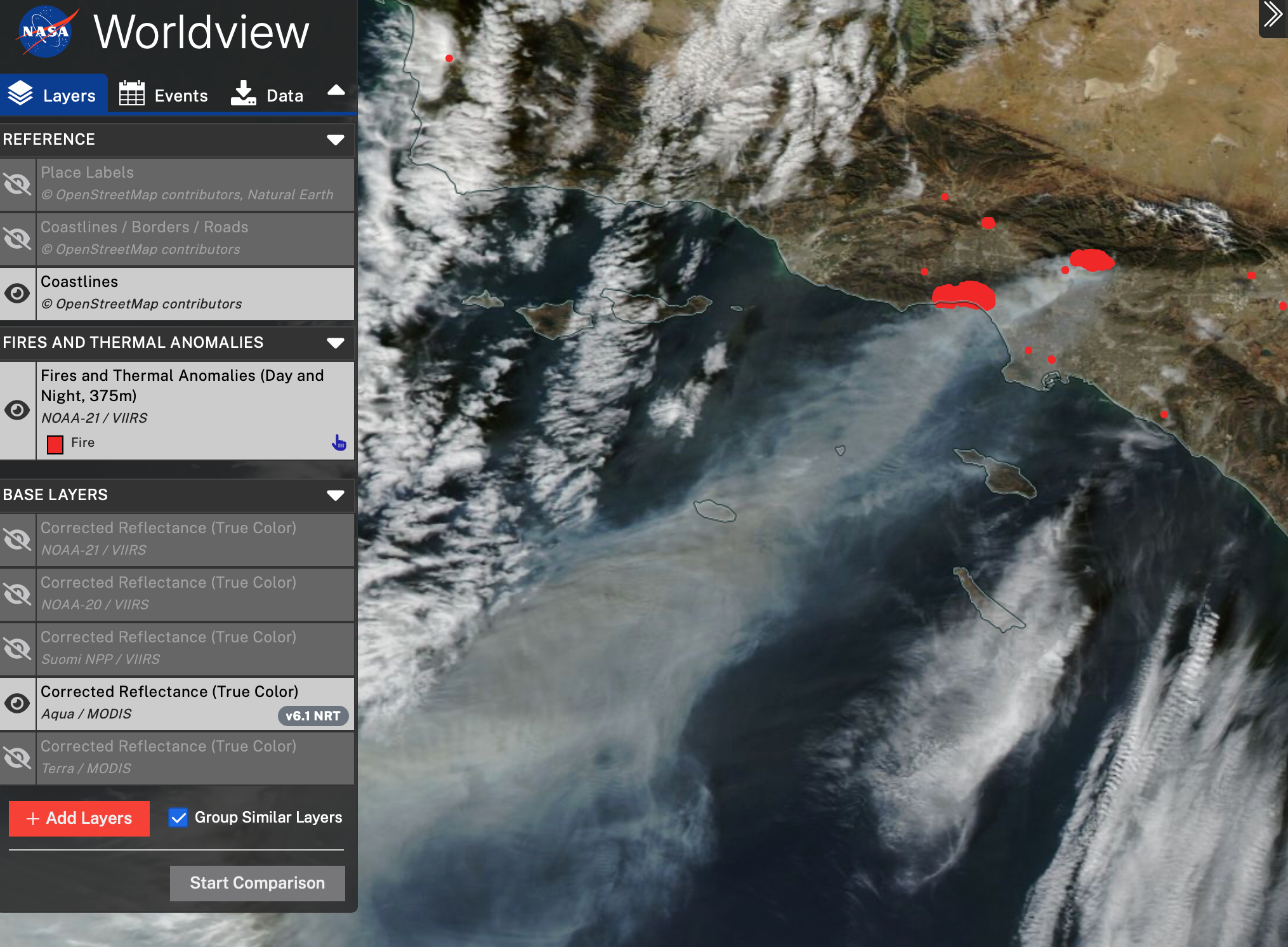

NASA’s Worldview is a user-friendly tool for observing wildfires and other natural events. View smoke plumes, thermal hot spots, weather systems, and burn scars with images and data layers from multiple satellites. The data is updated in near real time, and users can select from many different data layers and create customized images and animations.

This view shows multiple fires near Los Angeles, California on January 8, 2025. Explore this image or learn more about this event.Credit: NASA

This view shows multiple fires near Los Angeles, California on January 8, 2025. Explore this image or learn more about this event.Credit: NASA

-

Fire behavior is changing, and data is helping scientists learn more.

NASA’s satellite data is part of a global system of observations that are used to track fire behavior and analyze emerging trends.

Global Wildfire Information System (GWIS) This international collaboration gathers comprehensive global wildfire mapping, profiles of each country, and fire weather forecasts. The database includes active fire detections and near-real time burned area perimeters from NASA’s MODIS and VIIRS sensors.

Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED) Emissions from fires can be calculated based on the type of vegetation that burned and the size of the area burned. NASA’s MODIS and VIIRS data are used to determine the burned area. Screenshot of the Global Wildfire Information System’s current situation viewer

Screenshot of the Global Wildfire Information System’s current situation viewer -

Data can help manage the risk from wildfire smoke.

Wildfire smoke can travel thousands of miles and put millions of people at risk. Tiny particles in smoke irritate the eyes and throat, and can contribute to health problems such as reduced lung function, asthma, and cardiovascular disease.

When the sky turns hazy, many people turn to websites and mobile apps for real-time, localized information. Easily accessible air quality data allows people to make informed decisions about outdoor work or activities.

Air quality data from NASA and NOAA satellites is merged with ground-based air sampling to create the AirNow Air Quality map.

Google and NASA have expanded their partnership to include two new NASA data sets to help map and predict poor air quality.

The IQ Air map and mobile app use NASA data to show the location, size, and intensity of wildland fires.

NASA and the U.S. State Department are collaborating to provide air quality forecasts for all the approximately 270 U.S. embassies and consulates worldwide. NASA Data Helps Protect US Embassy Staff from Polluted Air

Air Quality: How NASA Tracks Air Pollutants as They Move Through the Atmosphere

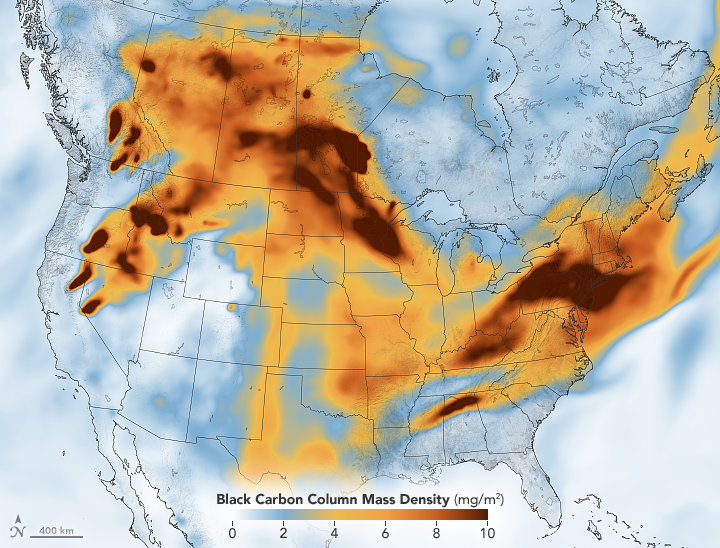

The concentration of black carbon particulates – commonly called soot – over North America on July 21, 2021, as multiple large wildfires were burning in the U.S. and Canada. Black carbon is just one of several types of particles and gases found within wildfire smoke. Learn more from Earth Observatory.Credit: NASA

The concentration of black carbon particulates – commonly called soot – over North America on July 21, 2021, as multiple large wildfires were burning in the U.S. and Canada. Black carbon is just one of several types of particles and gases found within wildfire smoke. Learn more from Earth Observatory.Credit: NASA