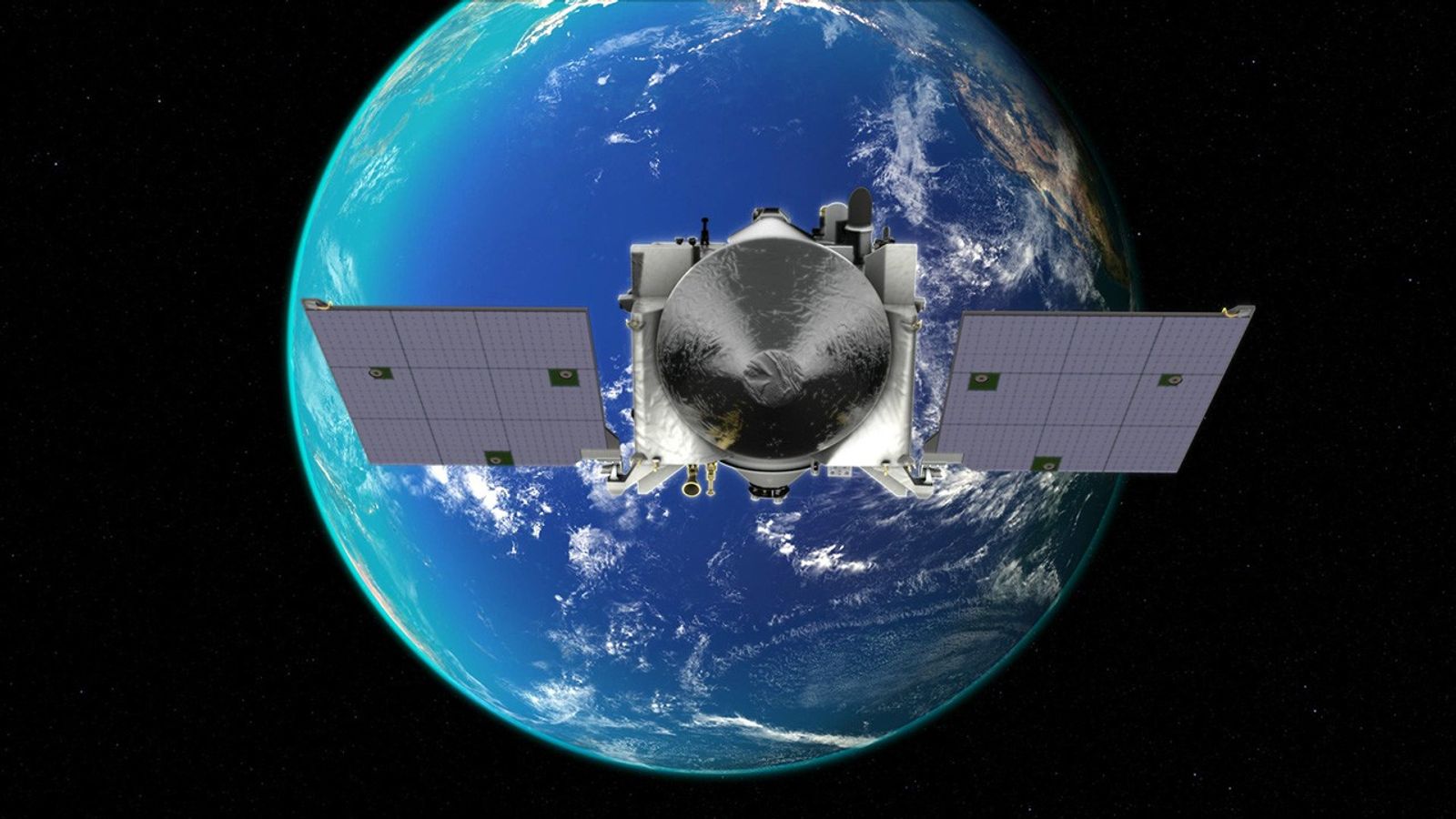

Launched on Sept. 8, 2016, the Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, and Security-Regolith Explorer, or OSIRIS-REx, spacecraft traveled to a near-Earth asteroid named Bennu to collect a sample of rocks and dust from its surface.

This mission put Bennu at the center of one of the most ambitious space missions ever attempted. But the humble rock is but one of about 780,000 known asteroids in our solar system. So why did scientists pick Bennu for this momentous investigation? Here are 10 reasons:

1. It's close to Earth

Unlike most other asteroids that circle the Sun in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, Bennu’s orbit is close in proximity to Earth's, even crossing it. The asteroid makes its closest approach to Earth every 6 years. It also circles the Sun nearly in the same plane as Earth, which makes it somewhat easier to achieve the high-energy task of launching the spacecraft out of Earth's plane and into Bennu's. Still, the launch required considerable power, so OSIRIS-REx used Earth’s gravity to boost itself into Bennu’s orbital plane when the asteroid passed our planet in September 2017.

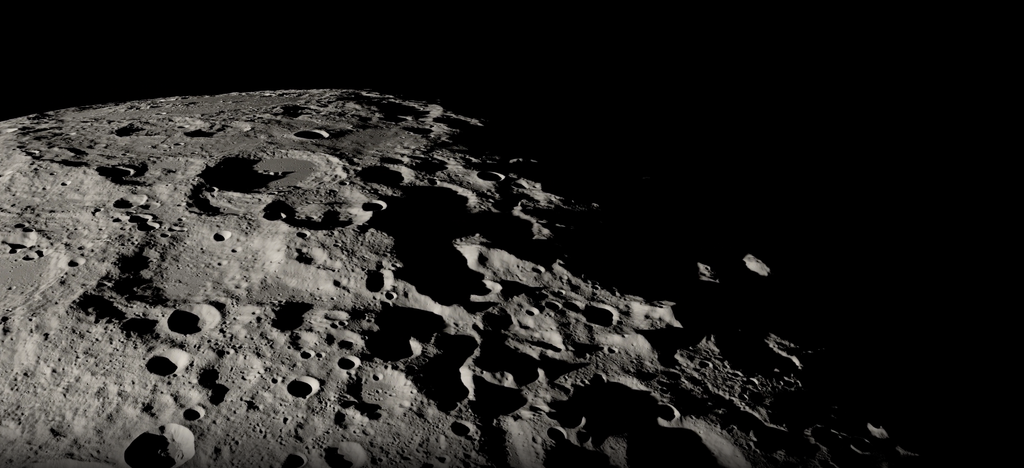

2. It's the right size

Asteroids spin on their axes just like Earth does. Small ones, with diameters of 200 meters or less, often spin very fast, up to a few revolutions per minute. This rapid spinning makes it difficult for a spacecraft to match an asteroid's velocity in order to touch down and collect samples. Even worse, the quick spinning can fling loose rocks and soil, material known as "regolith" — the stuff OSIRIS-REx is looking to collect — off the surfaces of small asteroids. Bennu’s size, in contrast, makes it approachable and rich in regolith. It has a diameter of 492 meters, which is a bit larger than the height of the Empire State Building in New York City. Bennu rotates once every 4.3 hours.

3. It's really old

Bennu is a leftover fragment from the tumultuous formation of the solar system. Some of the mineral fragments inside Bennu could be older than the solar system. These microscopic grains of dust could be the same ones that spewed from dying stars and eventually coalesced to make the Sun and the planets nearly 4.6 billion years ago. But pieces of asteroids, called meteorites, have been falling to Earth's surface since the planet formed. So why don't scientists just study those old space rocks? Because astronomers can't tell (with very few exceptions) what kind of objects these meteorites came from, which is important context. Furthermore, these stones, that survive the violent, fiery decent to our planet's surface, can get contaminated when they land in the dirt, sand, or snow. Some even get hammered by the elements, like rain and snow, for hundreds or thousands of years. Such events can change the chemistry of meteorites, obscuring their ancient records.

4. It's well preserved

Bennu, on the other hand, is a time capsule from the early solar system, having been preserved in the vacuum of space. Although scientists think it broke off a larger asteroid in the asteroid belt in a catastrophic collision between 1 and 2 billion years ago, and hurtled through space until it got locked into an orbit near Earth's, they don’t expect that these events significantly altered it.

5. It might contain clues to the origin of life

Analyzing a sample from Bennu will help planetary scientists better understand the role asteroids may have played in delivering life-forming compounds to Earth. We know from having studied Bennu through Earth- and space-based telescopes that it is a carbonaceous, or carbon-rich, asteroid. Carbon is the hinge upon which organic molecules hang. Bennu is likely rich in organic molecules, which are made of chains of carbon bonded with atoms of oxygen, hydrogen, and other elements in a chemical recipe that makes all known living things. Besides carbon, Bennu also might have another component important to life: water, which is trapped in the minerals that make up the asteroid.

6. It contains valuable materials

Besides teaching us about our cosmic past, exploring Bennu close-up will help humans plan for the future. Asteroids are rich in natural resources, such as iron and aluminum, and precious metals, such as platinum. For this reason, some companies, and even countries, are building technologies that will one day allow us to extract those materials. More importantly, asteroids like Bennu are key to future, deep-space travel. If humans can learn how to extract the abundant hydrogen and oxygen from the water locked up in an asteroid’s minerals, they could make rocket fuel. Thus, asteroids could one day serve as fuel stations for robotic or human missions to Mars and beyond. Learning how to maneuver around an object like Bennu, and about its chemical and physical properties, will help future prospectors.

7. It will help us better understand other asteroids

Astronomers have studied Bennu from Earth since it was discovered in 1999. As a result, they think they know a lot about the asteroid's physical and chemical properties. Their knowledge is based not only on looking at the asteroid, but also studying meteorites found on Earth, and filling in gaps in observable knowledge with predictions derived from theoretical models. Thanks to the detailed information that will be gleaned from OSIRIS-REx, scientists now will be able to check whether their predictions about Bennu are correct. This work will help verify or refine telescopic observations and models that attempt to reveal the nature of other asteroids in our solar system.

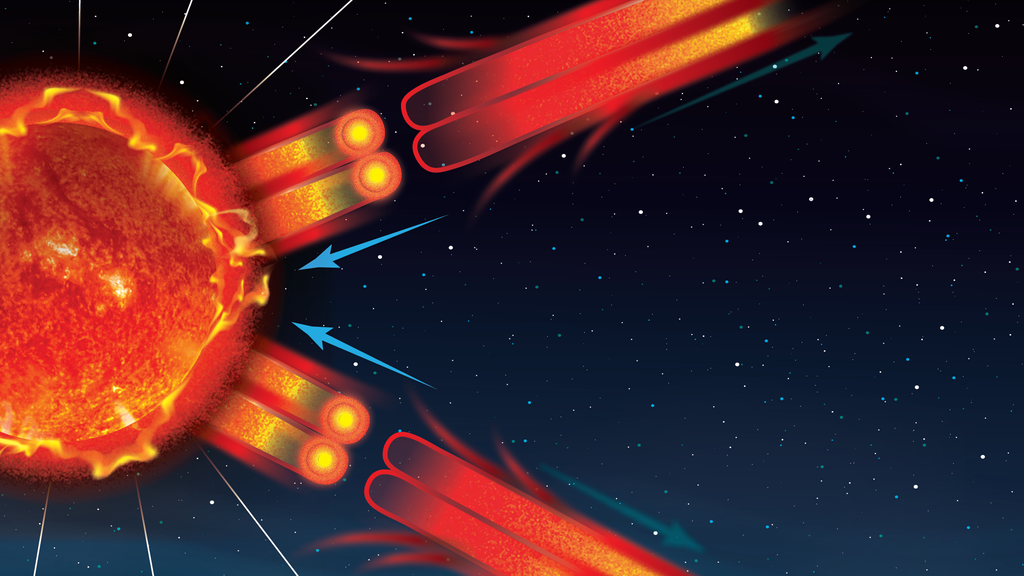

8. It will help us better understand a quirky solar force...

Astronomers think that Bennu’s orbit has drifted about 0.18 miles (280 meters) per year toward the Sun since it was discovered in 1999. This could be because of a phenomenon called the Yarkovsky effect, a process where sunlight warms one side of a small, dark asteroid and then radiates as heat off the asteroid as it rotates. The heat energy thrusts an asteroid either away from the Sun, if it has a prograde spin like Earth, which means it spins in the same direction as its orbit, or toward the Sun in the case of Bennu, which spins in the opposite direction of its orbit. OSIRIS-REx will measure the Yarkovsky effect from close-up to help scientists predict the movement of Bennu and other asteroids. Already, measurements of how this force impacted Bennu over time have revealed that it likely pushed it to our corner of the solar system from the asteroid belt.

9. ... and to keep asteroids at bay

One reason scientists are eager to predict how asteroids are drifting is to know when they're coming close to Earth. By taking the Yarkovsky effect into account, they’ve estimated that Bennu could pass closer to Earth than the Moon is in 2135, and possibly even closer between 2175 and 2195. Although Bennu is unlikely to hit Earth at that time, our descendants can use the data from OSIRIS-REx to determine how best to deflect any threatening asteroids that are found, perhaps even by using the Yarkovsky effect to their advantage.

10. It's a gift that will keep on giving

Samples of Bennu will be delivered to Earth on September 24, 2023. OSIRIS-REx scientists will study a quarter of the regolith. The rest will be made available to scientists around the globe, and also saved for those not yet born, using techniques not yet invented, to answer questions not yet asked.