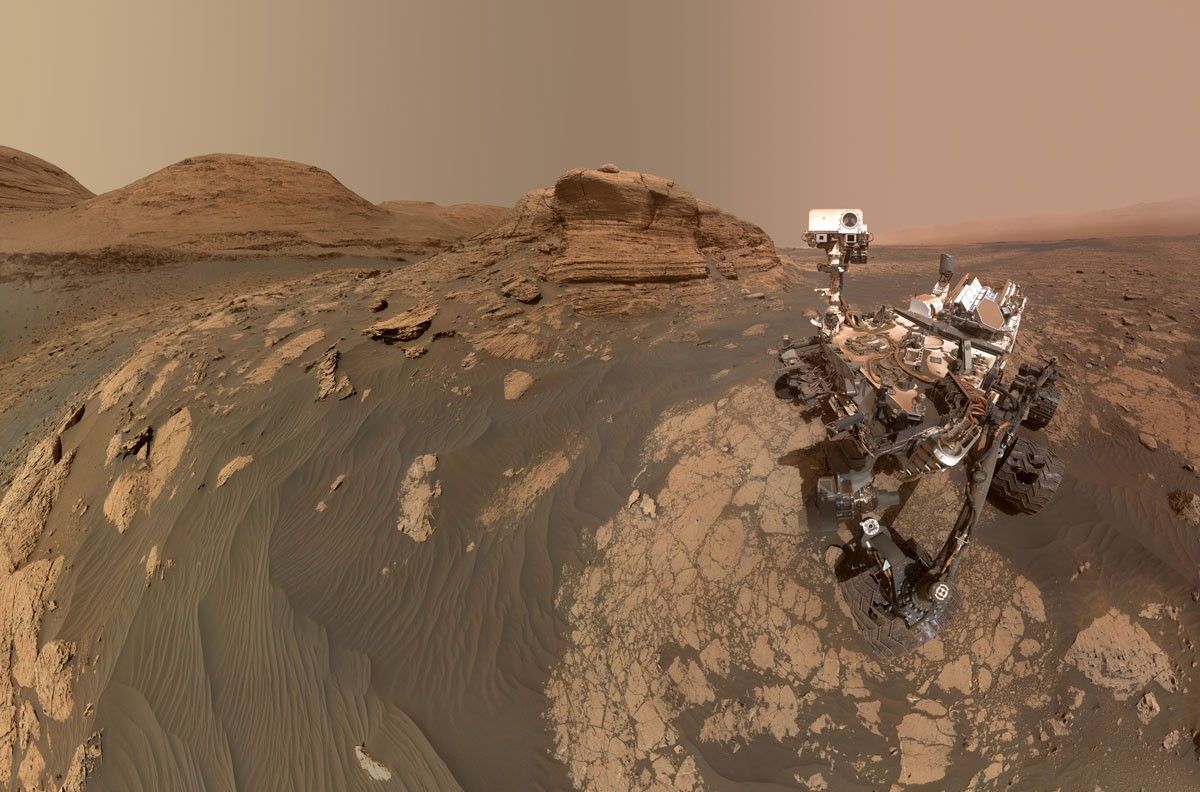

Over the ridge and around the sand ripples to South Séítah we go! After wrapping up science activities at the Citadelle location, including our first successful sampling on the Rochette rock, the Perseverance rover was hungry for more. With our Martian keepsakes in stow, Perseverance celebrated its 200th sol on Mars (September 11th, 2021) with a record breaking 175-meter drive northwest along Artuby ridge, a series of layered outcrops that outline the southern edge of the Séítah thumb and possibly represent a boundary between two geologic units. Perseverance took the wheel for most of the drive, covering 167 meters using the rover’s advanced auto-navigation function (or “Autonav”), a mobility software that allows Perseverance to map terrain and avoid hazards for longer drives.

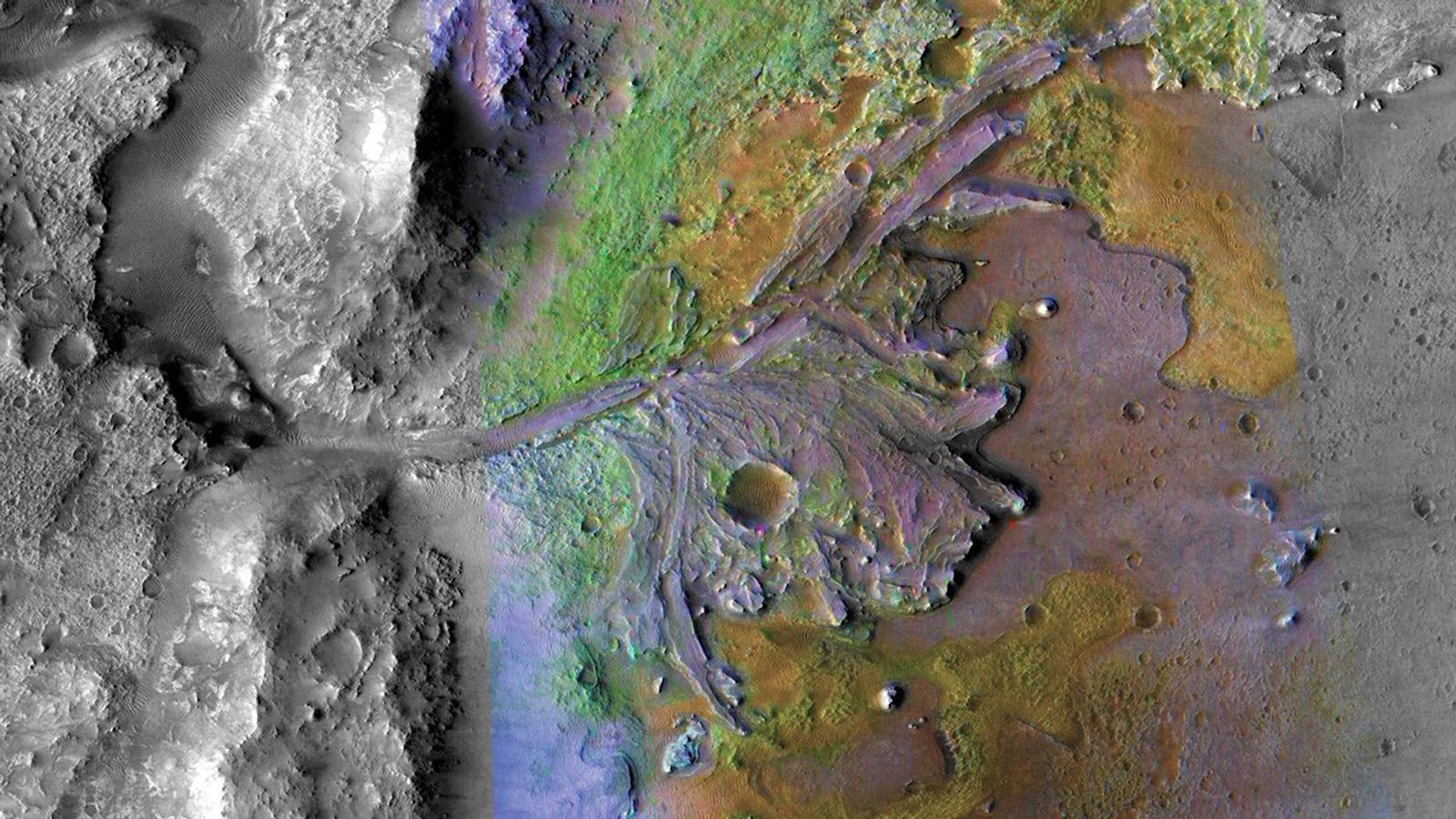

After collecting some images from the top of Artuby, Perseverance turned right and headed off the ridge as we dipped our wheels into the Séítah region. Thanks to some awesome scouting by the Ingenuity helicopter during flight 12 on Sol 174 (August 16th, 2021), the science team was able to get a preview of the rocks ahead and identify potential targets of interest for sampling. One rock that caught our eye was a thinly-layered outcrop called Bastide. The thin layers of Bastide suggest this rock may be sedimentary and deposited by water as a result of Jezero lake activity over 3 billion years ago, but further investigation is needed to confirm its origin. We got our first up close look at Bastide as we arrived at the outcrop on sol 204 (September 15th, 2021) after a series of drives. Since arriving, we have abraded the rock to reveal a fresh surface and better investigate the composition using our sophisticated suite of science instruments.

Some of our major science questions as we explore South Séítah are: How do these rocks relate to those previously explored in the “Crater Floored Fractured Rough” (“CF-Fr”) and do they represent a geologically distinct origin and time in Jezero’s history? Bastide may hold the answers to these questions and potentially provide a key sample in our cache that will one day be returned to Earth and studied by future scientists. But with Mars solar conjunction set to begin in early October, we will likely have to wait a little longer to sample our next Martian rock. In the meantime, we will have plenty of data to ponder and finalize a target for sampling once Mars comes back into view!

Written by Brad Garczynski, Student Collaborator at Purdue University