Assessing Landslide Hazards From Space

On May 28, 2025, the peaceful town of Blatten, Switzerland, was even more quiet than usual. Almost all of the 300 residents had been evacuated due to local geologists and glaciologists fearing the worst. That afternoon, those fears were realized, as 9 million tons of rock came crashing down on the town from the mountain above. For 800 years the village had existed, only to be buried in an instant by a landslide. Seeing this event in the news reminded me of how I and other scientists study landslides using satellite Earth observations and field methods. It reminded me of the importance of the chain of disaster risk information, from scientists recognizing and communicating a hazardous situation to those in danger taking action to mitigate their risk.

Landslides are diverse natural phenomena. They can exceed 50 mph or move less than a meter a year. Landslides have many causes, with heavy precipitation being the most common trigger for fast-moving landslides. While there are many ways that landslides can be studied on the ground, Earth-observing satellites are increasingly being used to study them globally.

While Blatten serves as an extreme example, smaller landslides are also dangerously common. According to the World Health Organization, landslides caused more than 18,000 deaths globally between 1998 and 2017. In that same period, they affected an estimated 4.8 million people, blocking roadways and isolating rural communities, or causing flooding by obstructing rivers. Earth scientists can combine ground observations and satellite data to better understand where landslides are likely to occur. This information, when carefully communicated to those in danger, can help save lives.

Field Trip

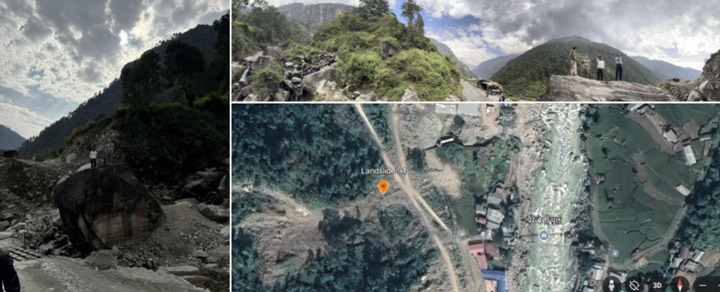

In November of 2024, we visited the sites of various landslides in the Bagmati Province in northern Nepal—a region that is especially susceptible to landslides—to better understand how satellite data can help predict landslides and keep communities safe.

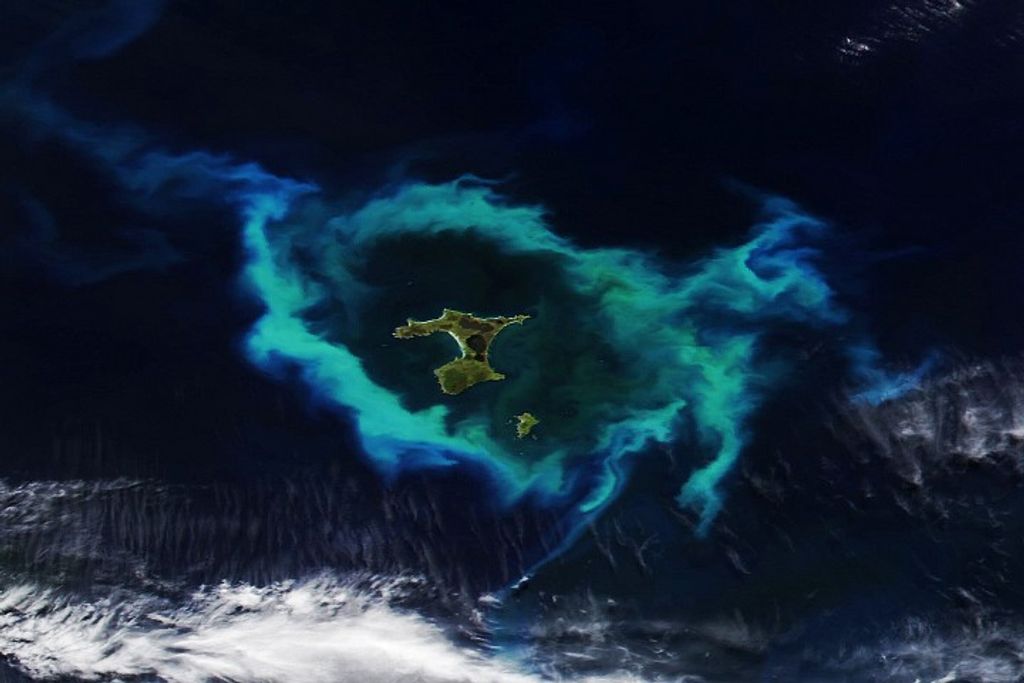

Visiting landscapes like this can show us why even small landslides can cause big problems. As we left Kathmandu and headed into the Himalayas, we encountered a landslide near the village of Manakamana that had occurred right next to a fast-moving river. During the monsoon season from June to September, heavy rains frequently trigger landslides that block rivers, quickly turning a minor landslide into a major flood. Disaster scientists call these “cascading hazards,” when one hazard triggers or amplifies another. Looking at satellite imagery, we see the potential cascading hazards that a landslide here could trigger. Several farms are located just downhill from the landslide. A larger landslide could have dammed the river, flooding the crops and houses.

Even relatively small landslides can change the landscape enough to have serious downstream effects on the datasets scientists rely on. When landslides shift terrain or block river channels, the maps we use to study and predict hazards suddenly become outdated. If these maps and datasets aren’t updated quickly, forecasters and emergency managers may miss key information like a shifted flood zone or a blocked evacuation route.

Our tour also demonstrated how landslides can have cascading effects on infrastructure. At this point in our journey, we learned that a landslide had blocked the highway ahead, forcing us to take a bumpy and treacherous side road. When landslides like this occur, they endanger motorists, cut off trade routes, and disrupt the livelihoods of local communities. If someone needs food, water, or medicine, a landslide could mean a life-threatening delay, even if it happens dozens of miles away.

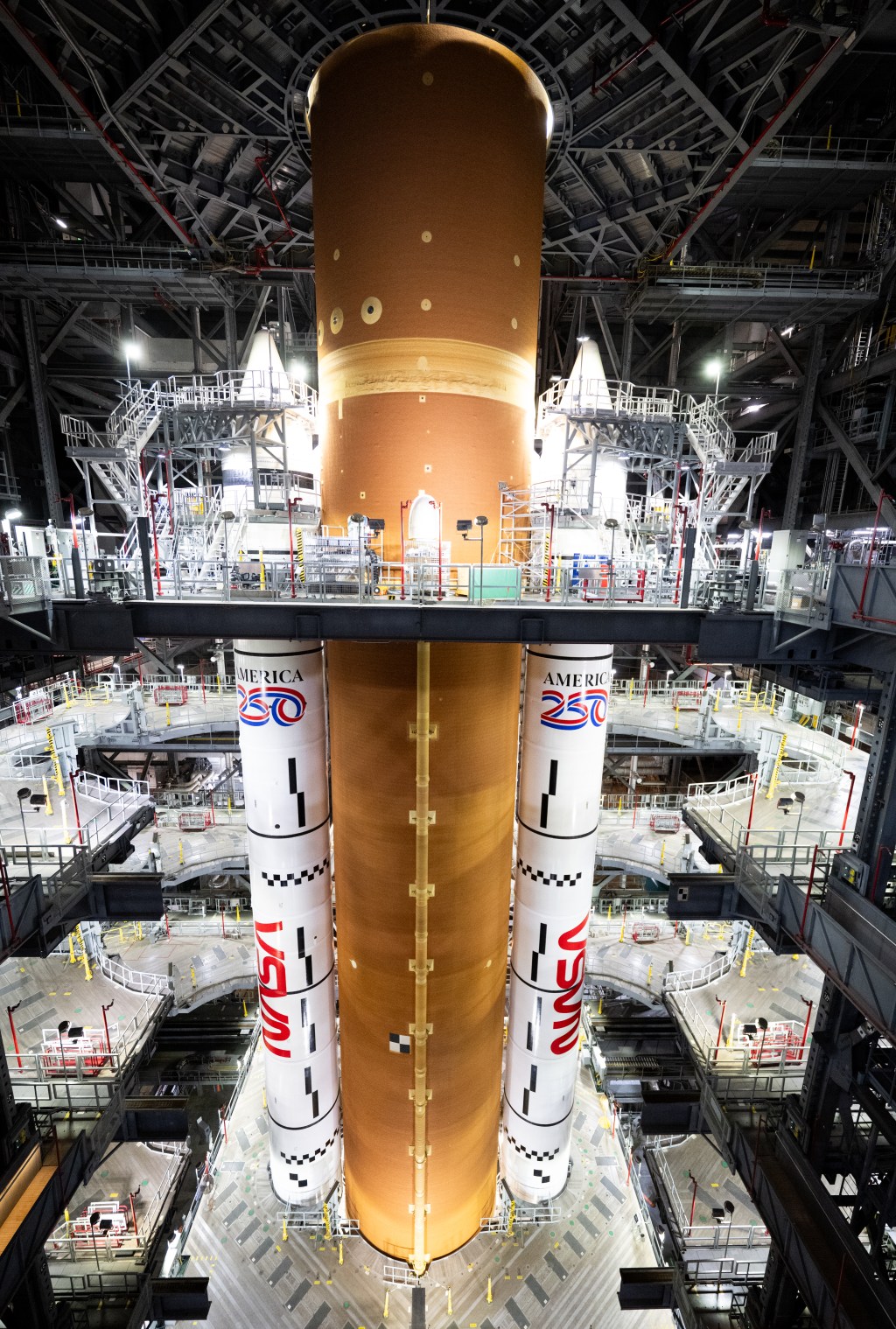

Another challenge faced by communities in this region is a lack of land use planning. Houses occur on slopes that can be subject to large landslides like the one pictured above.

Monitoring this region from space can reveal whether the slope may be prone to future landslides and if the community is at risk.

How We Study Landslides

While natural-color satellite images are great for seeing where landslides have already occurred, they are not very useful for predicting them. However, satellite data are useful for things like estimating precipitation, soil moisture, and slope. Putting this information together can help predict where catastrophic, fast-moving landslides are likely to occur. This is precisely what is done by the Landslide Hazard Assessment for Situational Awareness Model, or LHASA, which monitors landslide hazards in near-real time. Developed by scientists at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, LHASA combines satellite-derived precipitation and soil moisture with information on slope, geology, and earthquake risk to map high-risk areas so communities can take precautions.

Early action systems like LHASA predict where fast-moving landslides occur, but their slow-moving counterparts can be equally problematic. Not only do slow-moving landslides cause damage to infrastructure like houses and bridges over time, but they can be triggered into catastrophic, fast-moving landslides after heavy precipitation or earthquakes. These slow-moving landslides creep too slowly for humans to notice, but their movement can be detected by radar satellites. The incorporation of slow-moving landslides into early warning systems like LHASA paints a more complete picture of landslide risk.

Developing a scientifically sound early warning system is just half the battle—trust must also be built with the communities using the system. Users of an early warning system may inherently distrust a system for many reasons. For example, those most affected by landslides are often not included in the design of these systems, so they may feel like their perspectives are not considered. Furthermore, scientists must limit false positives—when an early warning is issued, but no disaster occurs—as people will lose trust in a system that constantly gives false alarms.

To mitigate distrust in these early warning systems, organizations like People in Need and the Community Rural Development Society of Nepal work directly with community leaders to integrate their knowledge into their early action systems. By asking people to recount personal experiences of natural disasters or stories they have heard from their ancestors, the early warning system considers the understanding of landslides from both scientists and the user community. This process of co-development builds trust with communities.

Looking Forward

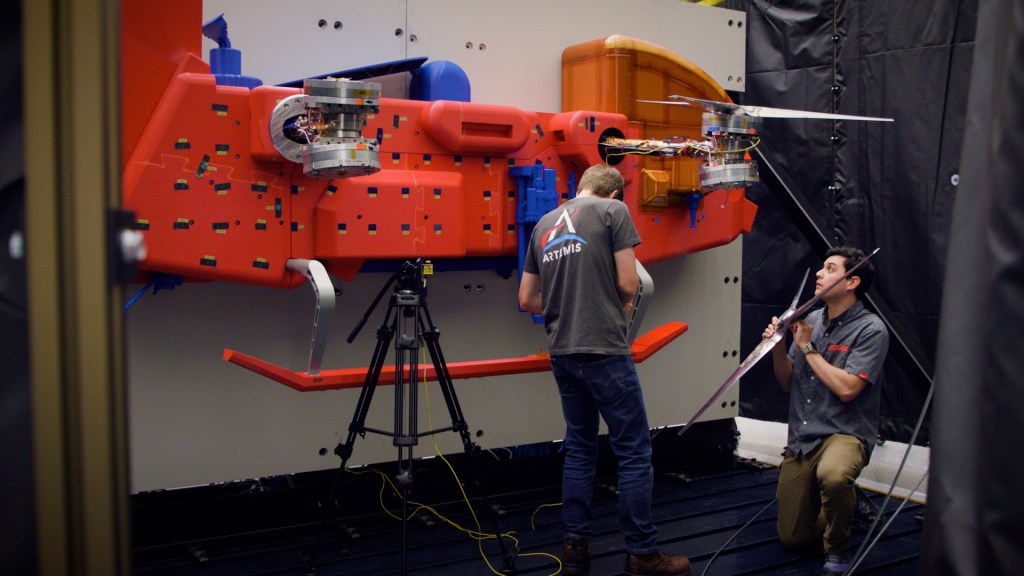

Earth-observing satellites still have limitations for studying landslides. Even the best publicly available optical imagery from U.S. satellites has a resolution down to around 15 meters, and small landslides can destroy homes and lives on a scale of 10 meters or less. What’s more, dense vegetation can limit the application of radar to study landslides. Fortunately, new satellites like the NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar, or NISAR, which launched in July of this year, are equipped to combat both of these challenges.

NASA launches Earth-observing satellites like NISAR to help protect lives and livelihoods in the United States, too. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that landslides result in more than $1 billion in annual economic losses in the U.S. from the destruction or disruption of highway routes, contamination of water, and direct property losses. Studying landslides in places as remote and geologically unique as Nepal allows scientists to better hone these technologies for use in the U.S. As we continue to improve our understanding of landslides from space, we will build better predictive systems to protect lives and livelihoods.

References & Resources

- Handwerger, A. L., et al. (2019) Widespread initiation, reactivation, and acceleration of landslides in the northern California Coast Ranges due to extreme rainfall. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface, 124 (7), 1782-1797.

- Huang, M.-H., et al. (2017) Coseismic deformation and triggered landslides of the 2016 Mw 6.2 Amatrice earthquake in Italy. Geophysical Research Letters, 44 (3), 1266-1274.

- Kirschbaum, D. and Stanley, T. (2018) Satellite‐based assessment of rainfall‐triggered landslide hazard for situational awareness. Earth’s Future, 6 (3), 505-523.

- Mansour, M. F., et al. (2011) Expected damage from displacement of slow-moving slides. Landslides, 8, 117-131.

- The Guardian (2025, June 1) This Is Ground Zero for Blatten’: The Tiny Swiss Village Engulfed by a Mountain. Accessed August 29, 2025.

- Stanley, T., et al. (2021) Data-driven landslide nowcasting at the global scale. Frontiers in Earth Science, 9, 640043.

- World Health Organization (2025) Landslides. Accessed 27 June 2025.