Count on Me: The Beauty of Citizen Science

Crawling on my hands and knees through the buckwheat and scrub shrubbery as passenger jets roared overhead was how I made my way into the world of citizen science.

Fresh out of high school, I had joined my friend Timothy Dahlum and Dr. Rudi Mattoni at a patch of land squeezed between the runways of LAX and the Pacific Ocean, to search for an elusive, possibly extinct member of the Lycaenidae Family: Euphilotes battoides allyni, also known as the El Segundo Blue Butterfly.

Little did I know when I set out in my grungy jeans and well-worn Vans that day in 1992, I was starting down a road that would lead me to far more involved areas of science – and even to becoming part of a NASA space mission.

I fell in love with science and space when my dog was still taller than me, and dreamed of working at NASA. That love never left, I’ve tended to seize any science opportunities I could find. Whether it was a project to count and catalog the suburban tree species of the Los Angeles area, or to sample the waters of the local streams and springs for pollutants, I was there with bells on (often literally). From tracking bees to counting and cataloging wildflowers, to participating in coastal and mountain cleanup days, to the SETI@home program, I happily immersed myself in the world of citizen science.

I spent weekends doing surveys of the medical and mental health needs of the local homeless population and weeknights scanning through WISE and NEOWISE data for deep space objects and brown dwarfs. Over the years I have counted everything from wildebeests to bees, bats to butterflies. And bacteria. And birds. And wildflowers.

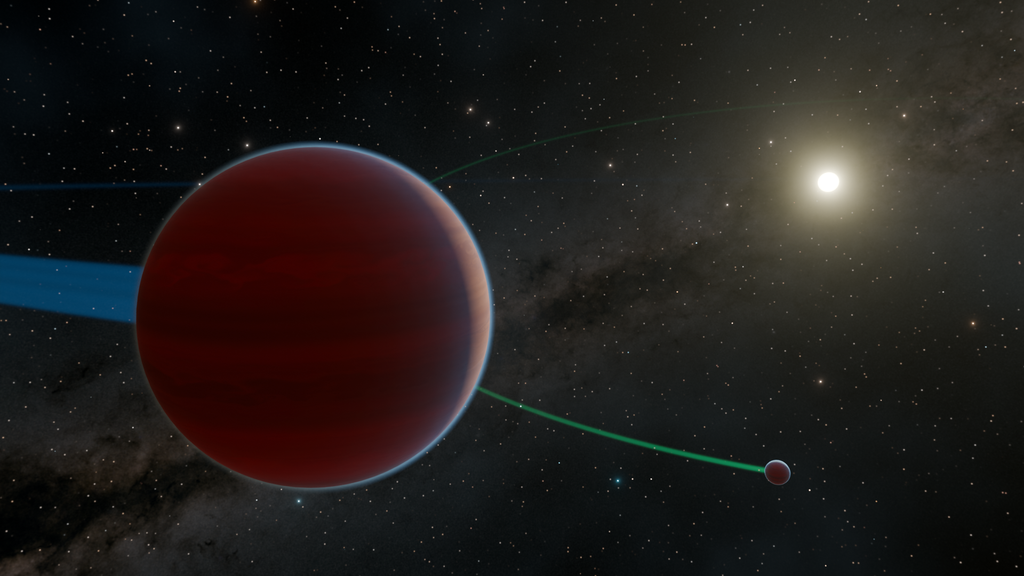

I won’t lie, there was a lot of counting involved, but there were also a lot of other activities, like classifying galaxies and searching for fossils, comets, supernovae — even tiny particles called muons. I spent stints of time scouring through ancient manuscripts and transcribing immigrations documents, and to this day I still spend at least one hour once a week searching for the ever shy and introverted Planet 9 (I think we might be soulmates).

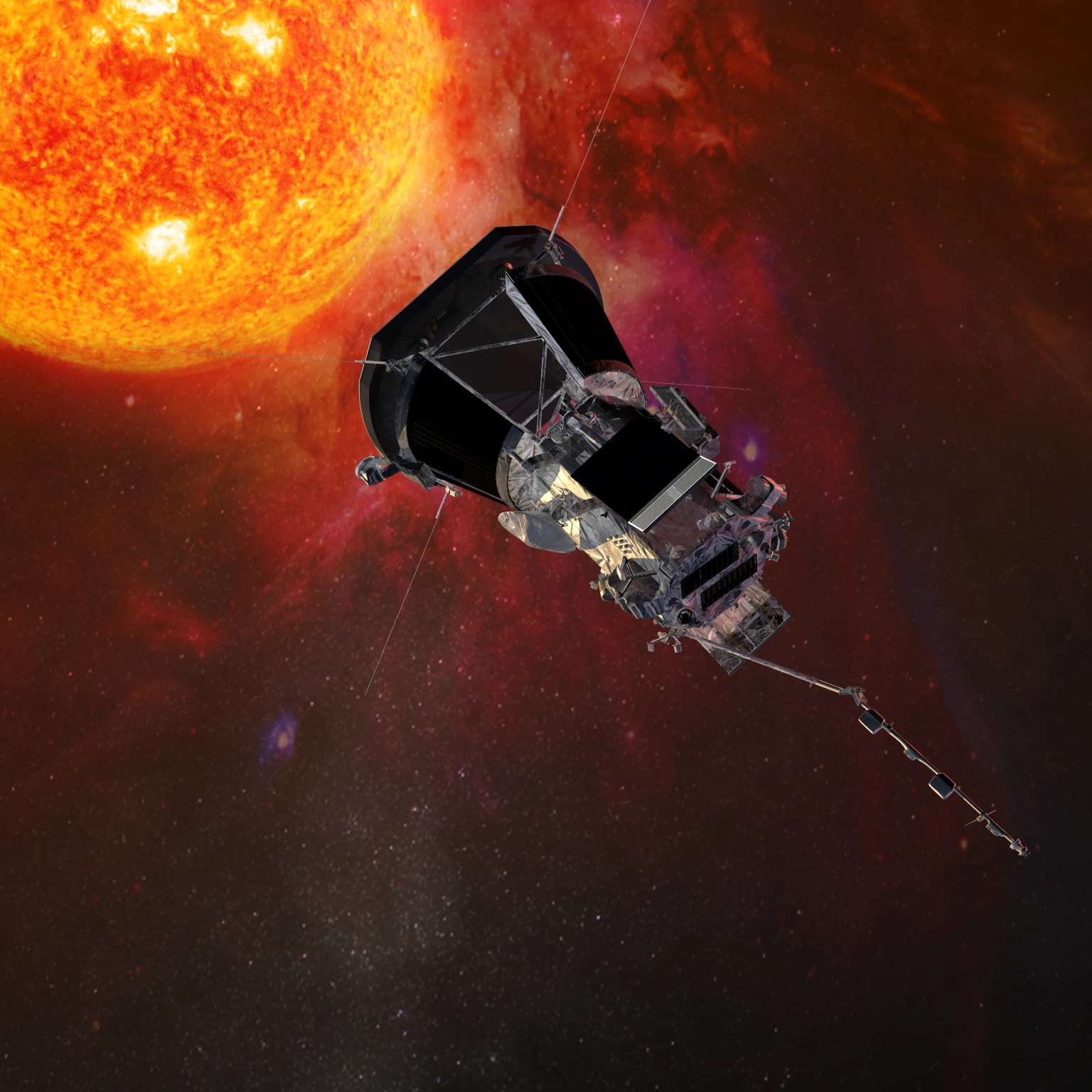

During the August 2017 solar eclipse, I joined tens of thousands of other citizen scientists using NASA’s Globe Observer app to gather data about the temperature, winds, clouds and insect and animal activity before, during, and after the eclipse. Altogether we gathered more than 100,000 pieces of data that day. Citizen science is fun. But more importantly, it’s useful. In many ways citizen science is a form of observational crowdsourcing. It allows large numbers of individuals to sift through the information that would take individual scientists years of their life, if not a lifetime itself. Just like actual scientists, citizen scientists like me delight in being useful and learning things, but also find it thrilling to be a part of something bigger than themselves.

Part of the joy of citizen science is that anyone with an interest can not only join in, but is encouraged to do so. And even though it doesn’t require a science degree to get involved, you can bet that there are people who have decided to pursue one after whetting their appetites with these programs — myself included. In many ways, citizen science is the bellows in the forge of science, breathing excitement and interest into an entirely new audience of people.

Over the course of my life I’ve had various kinds of jobs in the medical industry, finance, software, sales, education. I was even a tattoo artist. All the while I continued participating in citizen science. Like so many things in life, you never know where things may lead you.

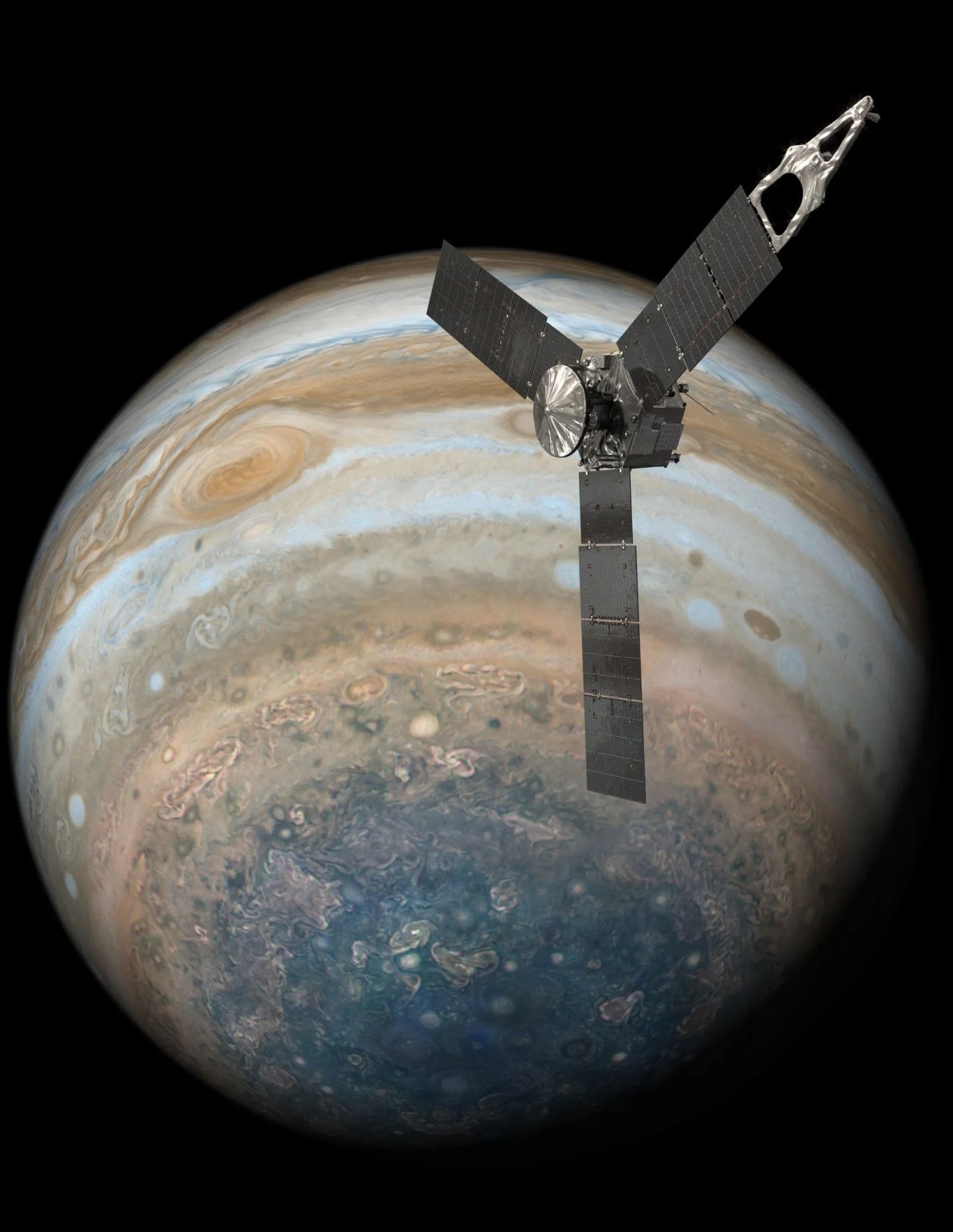

About 10 years ago, I suffered from severe complications of a rare neurologic disorder, which caused me to experience traumatic brain injury and to lose the majority of my vision. My life as I knew it came to a screeching halt — I had to get acclimated to life without a fully functioning brain and eyes. At the same time, my disability forced me to appreciate the beauty of the sky and space even more, and I became even more inspired to make a difference in space science. Three years ago, I began a bachelor’s degree in planetary science and astronomy. In December 2017, my dream of working at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory came true: I am now an assistant to the science team on the Europa Clipper mission.

If someone had asked me 25 years ago while I was crawling through the brush looking for those tiny blue butterflies, where I thought it would take me, I never would’ve suspected that it would lead to working on a NASA mission to look to look for the ingredients of life on an icy moon of Jupiter. But here I am, and I’m eagerly anticipating all of the unknown things sure to be found once we get there.