An interview with David Breashears

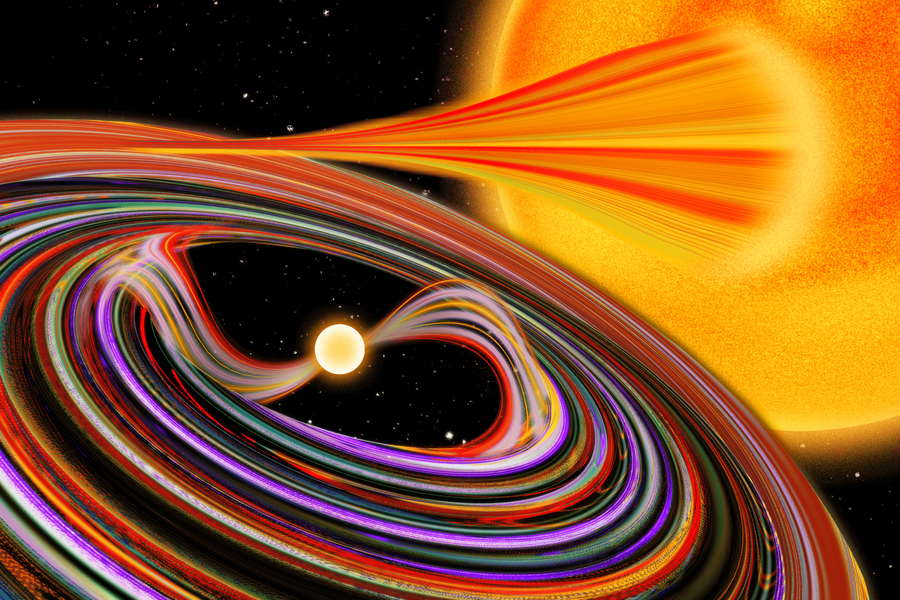

Pictured here is the West Rongbuk glacier in Tibet, just north of Main Rongbuk glacier, photographed in 1921 and in 2007. Credit: Major E.O. Wheeler and David Breashears, respectively.

David Breashears summited Mount Everest for the first time in 1983. His films, photographs and testimonies from the peak, 29,029 feet (8,848 meters) above sea level, have earned him fame as an adventurer and photographer. Now, as the founder of GlacierWorks, Breashears uses his climbing experience to tell the story of a changing region.

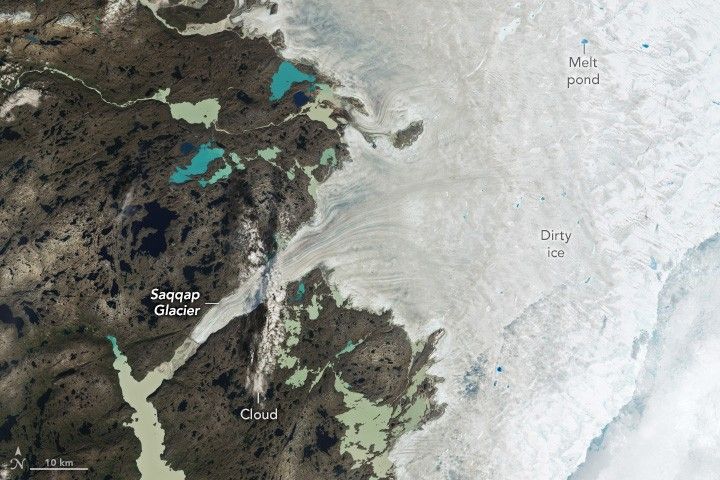

The project began on a 2007 climb, when Breashears duplicated George Mallory’s iconic picture of Everest from 1921 and was shocked by the Rongbuk Glacier’s visible retreat. He repeated other early photographs and found the same trend: In the last century, every icy landscape changed dramatically. Expeditions can’t reach the region as easily as Alaska or Greenland, where ice melt is well monitored, so GlacierWorks offers virtual access using million-pixel panoramic images. The project has exhibited photographs at Everest base camp and in Beijing.

Tom Painter, a research scientist at JPL who studies the effect of dust on snow pack and snow melt around the world, said Breashears' work is making an important contribution to science. “In the Himalaya, we still have a horribly difficult time achieving the measurements we need to understand glacier retreat and the contributions to sea level rise," Painter said. "These high-resolution, precise images allow us to understand the changes in mass across a half-century or even a whole century.”

We caught up with Breashears at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in August.

How did you evolve from a climber into a communicator?

That’s a very personal journey for everyone. What influenced me was my friendship with Sir Edmund Hillary. I remember talking about Everest, getting caught up in excitement, and he told me, “Someday, you’ll turn your gaze from the summit to the valleys, because that’s what really matters.” I may have climbed this mountain, but my more important work would follow that. Years later, when I first held up Mallory’s picture and took that photo, I realized I’d been traveling in these mountains for almost 30 years and change had been happening beneath my feet. I needed to know more about it.

For scientists, even those doing a lot of work in Alaska and on the Greenland ice sheet, the Himalaya provide extraordinary challenges. There are tensions along the borders, plus it’s impossible to reach most of the glaciers if you don’t know how to climb. I thought I could apply my skills to do something meaningful. I’m a storyteller, so I set out with a camera, hoping to show the difference between the glaciers then and now. I wanted to use the tools I’d gained climbing to do something that means much more to me than my movies or books: Tell the story of the Himalayan climate and engage people in the science.

You displayed these photographs in exhibits at Everest base camp. Did you find more climbers interested in the valleys, like Hillary suggested, or just focused on the summit?

It’s amazing how many people just were not interested. They were interested in the summit and the parties – all the clichés about base camp are true. Just because people want to be in those mountains, it doesn’t mean they care about them. People go there just to get a feather in their cap. And in the mountain villages in Nepal and Tibet, the average citizen doesn’t have enough of an education to know what a carbon atom looks like. They hear a lot of people talking about climate change, but it’s a slogan – “save the Himalaya” – and people don’t really sit down to ask what’s happening. There, we hope to get people interested in science in general and give teachers tools to promote Earth science.

The East Rongbuk glacier, photographed in 1921 and in 2008. Credit: Major E.O. Wheeler and David Breashears, respectively.

You’ve said you don’t like to describe your work as “creating awareness.” Why is that?

It’s a very easy thing to do, “awareness.” You can go find two pictures on a website and say that you’re creating awareness, while the real hard work is taking people from awareness to impact. That’s why taking this imagery and moving it to exhibits, or to scientists at NASA, is important. We move from creating awareness of the change to saying, “look, here’s how it works, here are the mechanics and the science at work.” We’ve created teaching tools to use in classrooms. Awareness is soft. Everybody’s creating awareness. To make progress in this field, we need action.

How closely do you work with scientists?

To a lot of scientists, since we’re not collecting pure data, this isn’t something they recognize. We take multiple angle measurements to estimate the change in glacier height to within about six feet (two meters). We’ve learned to pitch a tent out in the landscape for a scale. These data points are too few and far apart to be useful to scientists, but we want to get viewers interested in science in general. If you’re a child or a student or a policymaker, these images get your attention. Then we can start a conversation about glaciers, the Himalaya, hydrology, black carbon, the albedo effect, and so many other things. The people who see this and get interested will be the ones making a difference years from now.

What’s next for GlacierWorks?

Because the success of our exhibit in Beijing last fall, the Ministry of Environment and Forests in India wants to display these exhibits in the country’s mountainous states. It’s a big project, and we don’t yet have images from the Indian Himalaya. We want to include Nanda Devi, the second-highest mountain in India, and document the eastern side of Kangchenjunga on the border of India and Nepal, the highest peak in India. If we’re going to document those mountains, we need to get started this fall.

Explore the Himalaya online at GlacierWorks.org.